A novel that shows the power of #MeToo

Winnie M Li’s story of sexual assault is hard to read. That’s precisely why it’s so important.

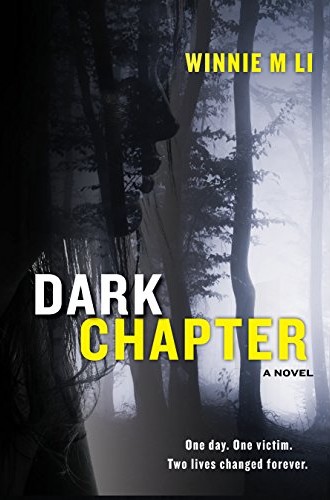

As I’ve watched the #MeToo campaign encourage new public conversations about sexual assault and sexual harassment, I keep thinking about a book I read a few months ago. It’s a novel that reads like a memoir and is being marketed as “inspired by true events.” Perhaps, like Nicole Kraus in Forest Dark, Winnie M Li intentionally blurs the line between memoir and fiction. Or perhaps Li is simply such a vivid writer that the prose feels undeniably real. In either case, Dark Chapter exemplifies what’s so powerful, painful, and necessary about the conversations that have been sparked by the #MeToo movement.

The novel begins with a young Taiwanese-American who (like the author) moves to London after graduating from Harvard and embarks upon a series of adventuresome (and sometimes naively foolhardy) solo travels. One day, while hiking on an isolated trail in Ireland, she happens to cross paths with a teenage rapist. The rest of the book recounts the savage attack and its aftermath. It’s hard to put down, so compelling is the story and the empathy it creates between reader and character. Will he be caught, and if so, will he be punished? How will she put her life back together?

Li’s prose feels more documentary than crafted, and her description of the sexual assault is brutally detailed. I found those pages hard to stomach, and I’ve never been sexually assaulted. I found myself wondering: if I had experienced the trauma of sexual assault before reading this book, would I find it healing to read about an assault in such detail, or would it be a painful trigger of my own trauma? Or perhaps both? Then I began to wonder: was it traumatic for the author, a survivor of a sexual assault like the one in the book, to write these painful words in so much detail, or was it therapeutic? Or perhaps both? More fundamentally, how do the dynamics of trauma and healing in reading and writing about sexual assault shape the ethics of how we engage with one another in this kind of communication?