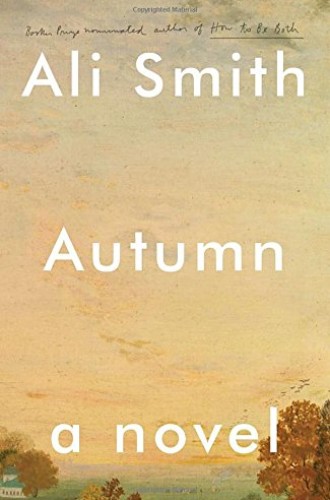

The autumn of our discontent

As leaves fall from the trees, Ali Smith helps us fall into the dreams and fears of her characters.

Ali Smith’s new novel, which has just made the shortlist for the 2017 Booker Prize, is delightfully enigmatic. The first of a quartet of seasonally-named novels, Autumn begins in a dreamscape and returns often to memories and dreams. One elderly character, Daniel, bedridden and unable to communicate, finds himself trapped inside the trunk of a tree:

It smells like a pine. He’s got no real way of telling. He can’t move. There’s not much room for movement inside a tree. His mouth and eyes are resined shut. . . . But the scent lightens despair. It’s perhaps a little like wearing a coat of armour except much nicer, because the armour is made of a substance through which the years themselves, formative, have run.

From the tree trunk, in his bed, he imagines an encounter with a celebrity and recalls a childhood moment with his sister. After pages and pages of memories, he returns to the tree, hoping for metamorphosis: “Cut this tree I’m living in down. Hollow its trunk out. Make me all over again, with what you scooped out of its insides. Slide the new me back inside the old trunk.” Evocative as it is, this vision doesn’t make a lot of sense. It happens early in the narrative, when readers don’t know Daniel well enough to guess at the beliefs or memories that create it.