It is surely a no-brainer that women and girls should be protected from violence and exploitation. Across the world, women and girls are disproportionately affected by issues of sexual exploitation, poor living conditions, and lack of educational opportunities. Meanwhile, online misogyny adds new lines to the old story of hatred of women. Every woman I know has been sexually harassed; many of us have been assaulted and much worse. For all the opportunities that exist for women and girls in the US and UK, systemic issues regarding our safety remain. And there is evidence that the Christian tradition has been part of the problem, going back to the biblical narratives that Phyllis Trible calls “texts of terror” against women.

But while the phrase “protect women and girls” may be a no-brainer, historically it has been used to undergird conflicting agendas. On the religious right it has been used to enforce modest dress for women or to prevent their financial independence, among other restrictions. On the feminist left it has been used to argue for the development of separatist movements that exclude men. In the UK, it has been disconcerting to witness how readily people from the left and right have found common cause in the claim that to better protect women and girls it is necessary to treat trans women, drag queens, and other LGBTQ people with suspicion.

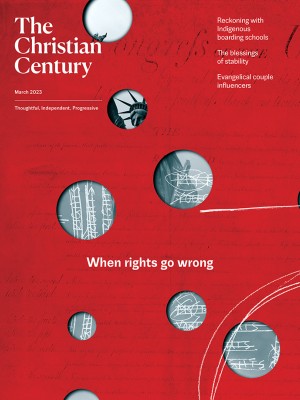

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

This is troubling on a personal level. As a trans woman, I am disturbed to be used as a prop in a culture war. As a feminist, I despair at how readily wedges are forced between cis and trans women, people who should be in solidarity with one another. As a theologian, I want to understand why concepts of womanhood, femininity, and vulnerability get weaponized; I want to see if theological thinking offers ways out of this mess.

Clearly, the mess is partially a linguistic one. If a phrase like “protect women and girls” can be used as a slogan to support radically different agendas, there is a problem. Literary theorist George Steiner once suggested that we are living in the aftermath of the broken covenant between the word and the world. That is, the words we use fail to grip onto reality and are used for seductive and manipulative purposes rather than to tell the truth. This is especially true in a consumerist culture, where words are used primarily to sell stuff. “The problem is that nourishing words are so hard to find,” says Barbara Brown Taylor, “words with no razor blades in them, words with no chemical additives.”

There is a problem of meaning. Words and phrases do not carry self-evident meanings. They will not yield simple definitions that grip onto the world, despite the fact that many wish they would. For many, words like woman, girl, man, and boy should have an obvious reference point: a biological reality, given in nature or revealed by God. According to such a view, to be a woman is a biological reality that cannot be gainsaid. For others, especially those who are alert to the messiness of language, the word woman—like any other word—can only be understood as it exists within social, political, and semantic discourse. They might even argue that biology, for all its powerful predictive power, is a discourse with a history and should not be taken as above critical analysis. In short, what we mean by woman or girl is not simply a matter of, for example, biological reduction to genetics—instead, it has millennia of shifting social meanings.

How might theology speak helpfully into a world where an imperative to protect women and girls can be used for such widely disparate agendas? As a feminist and queer theologian, I believe the Bible offers one route for liberative theology. It is no mere text of terror. It holds the seeds of our liberation from toxic patriarchal conceptions of identity that ruin and limit us. Here’s just one way in: Jesus.

Jesus models a way of being fully human that subverts a key problem which has damaging effects not just for women and girls but for boys and men: toxic masculinity. Consider Jesus’ death on a cross. It would have been coded in Roman imperial culture as shameful. Why? Because it reduced a man to a passive, humiliating death suitable only for a woman. While it is clearly wrong to suggest that being a woman should be parsed in terms of passivity, Jesus’ embrace of the position assigned to women in his day is quite a moment: the abiding gender stereotype which says that men are shamed by passivity is turned upside down.

On the cross, Jesus also shows abiding solidarity with women, those to whom violence and exploitation is most likely to happen. It should come as no surprise that this death is witnessed primarily by women disciples. At the cross, there is mutual recognition between Jesus and these women. The women will not abandon one whom they recognize as placed in a position they know only too well.

When Jesus says, from the cross, “My God, why have you forsaken me?” I think he cries out to the god who needs to die: the patriarchal god who only values power and power-over, the god of macho force and action. In that moment, I wonder if Jesus and the women of the cross discover the living God: the God of relationship and solidarity. This is the God found among those who stand by each other in their hour of need and will not give up until hope is found. Is it any surprise, then, that the first witnesses to Christ’s resurrection are women?