Tammy Faye Bakker’s story and Mark Driscoll’s in conversation

Church celebrity is complicated.

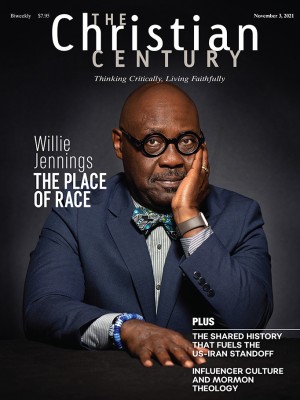

Tammy Faye Bakker was a caricature even while she was alive. A prosperity preacher, an exuberant performer, and the cofounder of the Praise the Lord media empire (with her husband Jim Bakker, who was later convicted of fraud and conspiracy), her outlandish makeup and outsize personality were parodied on late-night television and vilified by most commentators. Every portrayal of a big-haired, overly made-up evangelical preacher wife since then has had a little Tammy Faye in it.

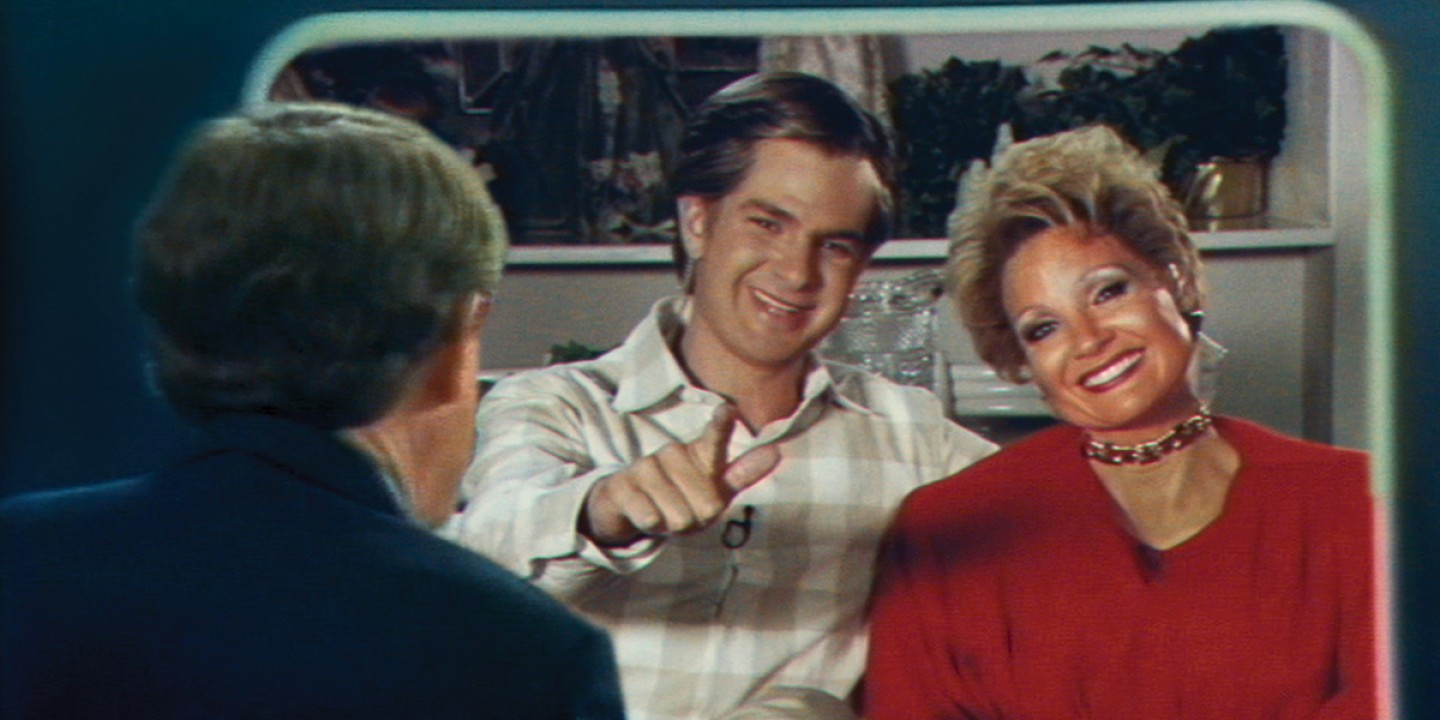

The Eyes of Tammy Faye (directed by Michael Showalter) wants us to know Tammy Faye beyond this caricature. In an early scene, Tammy (Jessica Chastain) and Jim (Andrew Garfield) are having a chaste picnic on the lawn of their conservative Bible seminary, having found each other in an exegesis class where Tammy defended Jim’s early prosperity teaching and Jim defended her choice of provocative makeup and tight-fitting sweaters. In sharing their conversion stories, Jim confesses that before he found the Lord he wanted to be a DJ. To his embarrassed delight, Tammy stands up, starts belting out “Blueberry Hill,” and insists that Jim dance with her on the lawn.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

This is Tammy’s spiritual gift, the movie suggests: an exuberant love of life and of other people that is fueled by her sense of God’s capacious, inexhaustible love. We see this extravagance in action repeatedly, from her first puppet shows for children to her controversial decision to openly embrace a gay pastor who was HIV-positive at the height of the AIDS crisis.

Her insistence on the radical love of God is positioned as a counterweight to the rising religious right, dominated by serious men in serious suits like Jerry Falwell (Vincent D’Onofrio) and Pat Robertson (Gabriel Olds), who are at once envious of the Bakkers’ media reach and wary of their feel-good prosperity teaching. (Falwell and Robertson want to remind the nation of its precipitous fall into the sins of liberalism, feminism, and homosexuality.) Falwell’s shadow, especially, looms hawklike over the Bakkers’ rise and eventual fall. The movie wants us to see Tammy as a victim of this patriarchal overreach but also as a counterforce refusing to be domineered. Tammy was preaching something too wild and lavish to be contained by the reactionary culture wars.

But surely there is some connection between the extravagance of God’s love she offered so willingly to everyone and the extravagance of her own lifestyle which contributed to the Bakkers’ public scandal and Jim Bakker’s conviction for fraud. The film doesn’t quite know what to do with this paradox—is Tammy a victim of a patriarchal power struggle that didn’t know what to do with her unwieldy theology, or is that theology itself part of the problem?

In the final scene of the movie, Tammy is invited to sing at an Oral Roberts University homecoming, after the sting of her public disgrace has mellowed. She is singing solo on stage, but the film shows us how Tammy experiences it—full choir rising up behind her, a return to the glory of the height of her fame—and the camera zooms in on the twinkle in her eyes. This could be the gleam of a con artist who has played the long game and found her mark. Or it could be the bedazzled joy of someone experiencing the grace she always taught. One way or another, Tammy is determined to tap into the power that threatens to eject and disgrace her and to make that power her own.

Explaining the powerful mix of celebrity culture, charisma, and patriarchal fetish is the obsession of a new long-form podcast, The Rise and Fall of Mars Hill, produced by Christianity Today and hosted by Mike Cosper. It is about Mark Driscoll, erstwhile superstar of evangelical counterculture in the early 2000s, and the collapse of the church network he built. It circles around its topic, going back in time to trace the roots of Mars Hill Church and to situate the “young, restless, and Reformed movement” in a longer genealogy. It brings in experts of all kinds—insiders with first-person accounts, sociologists, anthropologists, historians, trauma specialists—to peel the layers of the Driscoll onion.

If you were formed in this tradition or wounded by it or professionally invested in understanding it, the podcast is electrifying listening. But it is clearly created for people still inside evangelicalism, and it walks a strange line between exposing the truth in the name of the gospel and trying to convince evangelical listeners that Christians are allowed to expose the truth in the first place. It has garnered criticism both from evangelicals who accuse it of pandering to secular standards and from outsiders who think it pulls punches when it comes to the extent of Driscoll’s paranoid abusive power.

It was first recommended to me, however, by a friend who has no experience with Christianity and no previous knowledge of Driscoll or the twists and turns of evangelical church movements. She was hooked by the sheer strength of Cosper’s storytelling and analysis and fascinated by how much it helped explain something larger about American culture to her.

The desire to explain Driscoll and Mars Hill comes at moment when it is also clear that spiritual and theological sickness do not mean a lessening of cultural or political power. There is a general despair as many struggle to understand why so many White evangelicals voted overwhelmingly for Donald Trump and why so many of them have eased so comfortably into open White nationalism.

This larger field of explanation seems to be Cosper’s intention too. The tone is compassionate and humane—real people found meaning in this movement, and they weren’t all dupes—but the conclusion is clear: what went wrong at Mars Hill is a symptom of a much deeper sickness in White American evangelicalism.

But the podcast oscillates as to what the root cause and symptoms of this sickness are. For the first several episodes, it focuses primarily on the hypermasculinity of Driscoll’s theology and public persona and the trauma his patriarchal authority inflicted. As the podcast develops, celebrity itself becomes the root evil, along with the willingness of churches to give platforms to charismatic leaders who aren’t mature enough in the faith (or maybe just as people). After four years with a reality-TV star president, it is hard to argue with that.

The Eyes of Tammy Faye complicates this narrative. Her life was tangled in the same web of prosperity and charisma that ensnared Driscoll, and all the clues were already present in her own life to predict where a church like Mars Hill would later be headed. But unlike with Driscoll’s macho persona, it is impossible to imagine anyone taking back the nation under the banner of her eye makeup or feel-good preaching, no matter how charismatic she was. Revisiting her story in the shadow of Driscoll, who is an inheritor of the patriarchal control that hemmed in Tammy’s life at every turn, her hyperfemininity seems like a shield against a coming storm. As we try to find our bearings in that storm, we need both of these stories to complicate and inform each other—and to help us figure out what else we haven’t had eyes to see.

A version of this article appears in the print edition under the title “Dangerous celebrity.”