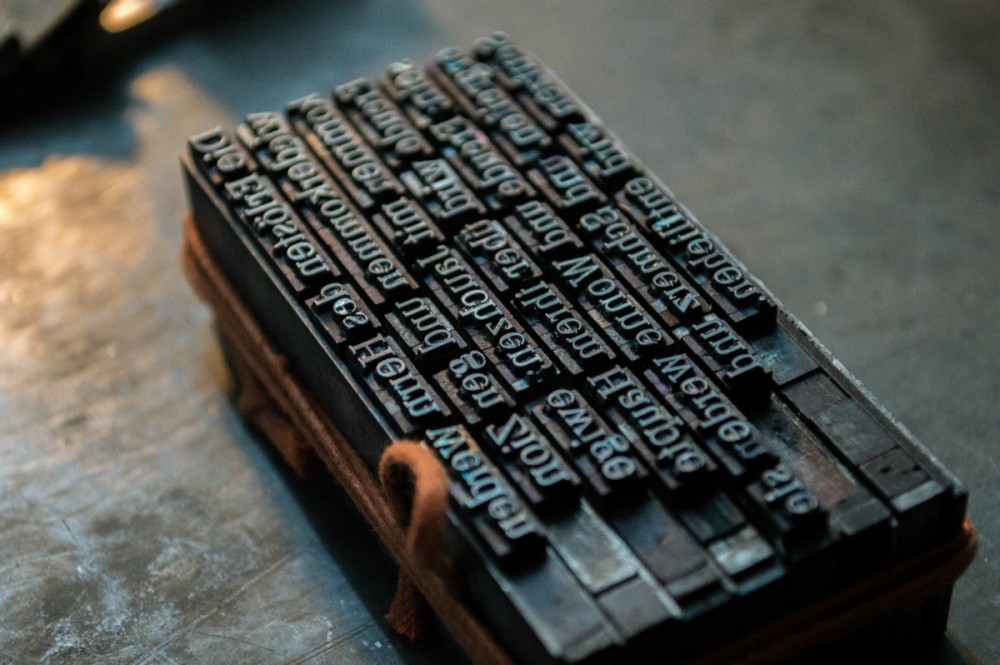

Words are composed of scant physical matter. Tiny scratches of graphite, minuscule droplets of ink, invisible rays from a screen, and sound waves emanating from human breath are about all the physical makeup they possess. However inconspicuous their material substance, words carry great significance. Every day we breathe something of our spirit into the consonants and vowels that constitute human speech. In some sense, we are our words and our words are us.

Most of us were taught somewhere in the course of our development that words have implications. The way we use them matters. They can coerce or liberate, create or destroy, motivate or paralyze. Thoughtfulness can make a life; thoughtlessness can break one. “If you get the right [words] in the right order,” says Tom Stoppard, “you can nudge the world a little.” If you get the wrong words in the wrong order, we might extrapolate, you can defile or even annihilate a relationship. Considerate words used with care form the substructure of trust between people.

I think increasingly about matters of language as I watch the cumulative effect of the boorish talk in political life these days. Many are growing accustomed to hearing groups or individuals targeted with vile language. Vindictive and ugly rhetoric, as in “Lock her up”—or “Lock him up,” as some now want to say—is hardly innocent and without consequence. A peek at history reveals case after case of regime leaders and followers who perpetrated violence against specific populations after they were publicly branded in this way.