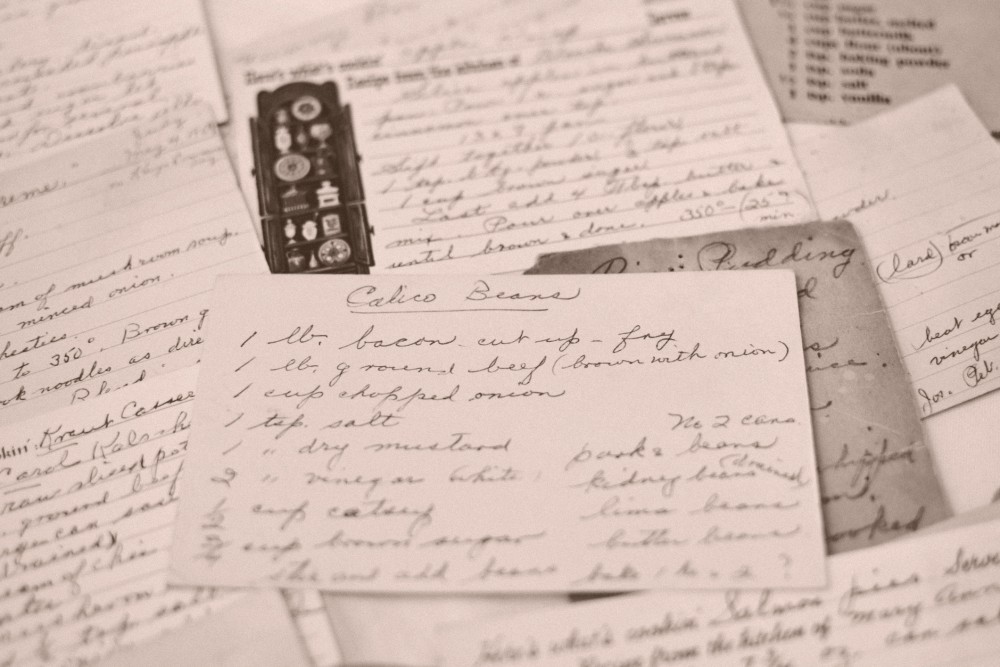

The floor under the bed in the master bedroom of my house is a repository for two things: dust bunnies and long-forgotten objects. I discovered the extent of both while preparing for new carpeting recently. One of the things I retrieved was a white plastic box of index cards. After wiping 22 years of dust off of the lid, the word “Recipes” came into view. When our mother died 37 years ago, I became heir of this stash—thanks either to a lucky draw among siblings or to selfish claiming rights on my part, I can’t remember which.

The dog-eared cards behind the “Cookies” tab provoked the most vivid memories. Fifty-year-old butter and corn syrup fingerprints blur the words penned in red ink. Mother taught us baking at an early age, which meant we spilled as many ingredients on the counter as ever landed in the bowl. If the tattered condition of the oatmeal chocolate chip card is any indication, those were our favorite. The recipe in which Mother had already increased the measurements was titled “Double Recipe.” My brother once took those words as an instruction, doubling the already-doubled recipe. I’m pretty certain he had enough cookies to feed the entire school.

Bequeathing recipes to loved ones doesn’t normally merit the attention of estate planning lawyers. Yet sharing recipes that have personal meaning can create the sort of legacy that transcends all monetary or legal value.