The National Day of Prayer and the sectarian group that uses its name

People often perceive the National Day of Prayer Task Force’s events as official. They aren’t.

In January, the National Day of Prayer Task Force changed the logo on its website. The old logo relegated the words “Task Force” to small type at the bottom. The new one omits them altogether—it’s just “National Day of Prayer” and a stylized American flag.

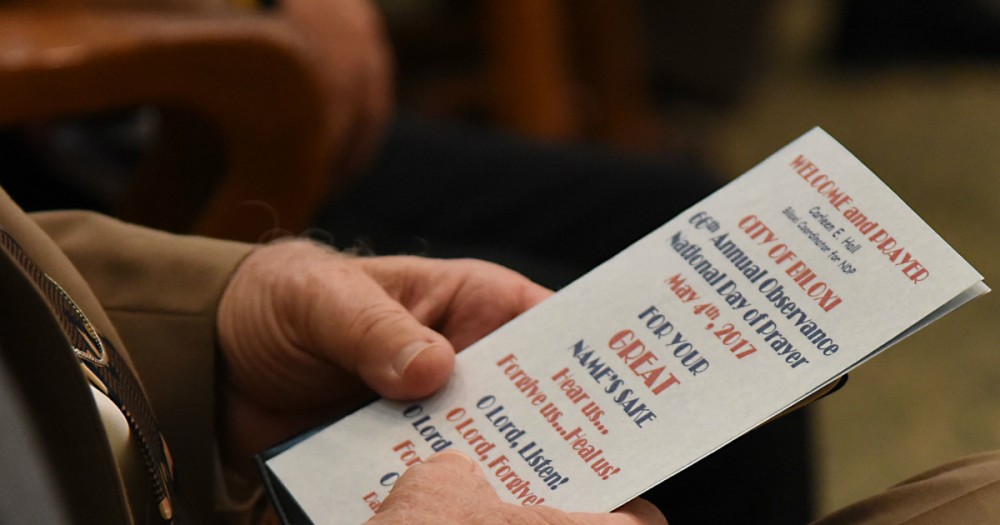

The new logo joins the group’s web domain (nationaldayofprayer.org) and social media identity (@NatlPrayer on Facebook and Twitter) in perpetuating a confusion of terms. National Day of Prayer is in fact simply the name of a federal law, a nonsectarian annual observance enacted by Congress that falls on the first Thursday in May. The National Day of Prayer Task Force, on the other hand, is a conservative evangelical organization that’s behind the most prominent National Day of Prayer events. For years, these two very different things have frequently been conflated by casual observers, who often perceive the task force’s work as representing the law in some official way. It doesn’t. (The National Prayer Breakfast in February is yet another entity, hosted by an unrelated group.)

The logo change came as part of a broader website redesign alongside the release of Pray, a new magazine published by NDPTF. (That’s an acronym the organization generally avoids in favor of NDP, though an unused @NDPTF Twitter account does exist.) It’s not clear, however, what prompted the specific decision to drop “Task Force” from the logo, and NDPTF didn’t respond to requests to comment for this article. In any case, the more the group calls itself simply National Day of Prayer, the fuzzier the distinction becomes in the public eye—with consequences for the politics of the NDP law and of public prayer generally.