Why people still speak Guaraní

The Jesuits didn't impose a European language on the Guaraní people; they actively cultivated the indigenous one.

Globalization usually means the displacement of local and indigenous languages by the newer tongues of political and cultural hegemony—English, Spanish, or French. One significant exception to this process is the indigenous Latin American language of Guaraní, which not only flourishes in Paraguay and parts of neighboring nations but is commonly spoken by nonnative peoples. The stubborn survival of Guaraní recalls an epic moment in Christian missionary history.

In the 16th century, the Spanish and Portuguese conquered most of South America. The new colonial states were brutal in their treatment of the natives, bringing millions into forced labor, serfdom, or outright slavery. Large sections of the continent were open to the depredations of bandits, mercenaries, private armies, and slave traders—the notorious Paulistas or Mamelucos. Native groups suffered appallingly, societies were torn apart, and whole peoples were annihilated.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

Matters changed in the 1580s when the Jesuits arrived in the Río de la Plata basin. Well-intentioned clergy attempted to bring natives into protected reserves, or reductions, in what we would today call Paraguay and neighboring regions of Argentina, Brazil, and Bolivia. Initially, such schemes foundered on the colonial authorities’ reluctance to allow Indians to defend themselves with effective weaponry. Gathering natives into poorly defended settlements merely gave slavers the opportunity to grab larger groups of victims in a single raid, and raiders had no compunction about attacking priests or churches.

In the 1630s, the Jesuits developed a much more muscular approach, as they strengthened and expanded the reductions. Self-defense was the first necessity, and the Jesuits gave their converts firearms and trained them in modern tactics. The fathers organized well-armed native forces several thousand strong, which successfully resisted slave raiders, and on occasion even defeated Spanish armies.

These military achievements were the essential precondition for the expansion of the reduction settlements, which at their height in about 1730 numbered 30 missions. These theocratic communities were highly paternalistic and regimented, arranged in urban layouts designed to promote a communist utopia. Beyond accepting Catholic Christianity, native peoples were forced to adopt economic practices quite unfamiliar to them.

In modern eyes, the reduction system reflects attitudes that seem intolerably condescending to native peoples and cultures. But it is difficult to see what alternatives existed in the anarchic and even genocidal conditions of the time. In effect, the result was a virtually independent Native Christian state that was larger in area than most European kingdoms, with populations in the hundreds of thousands.

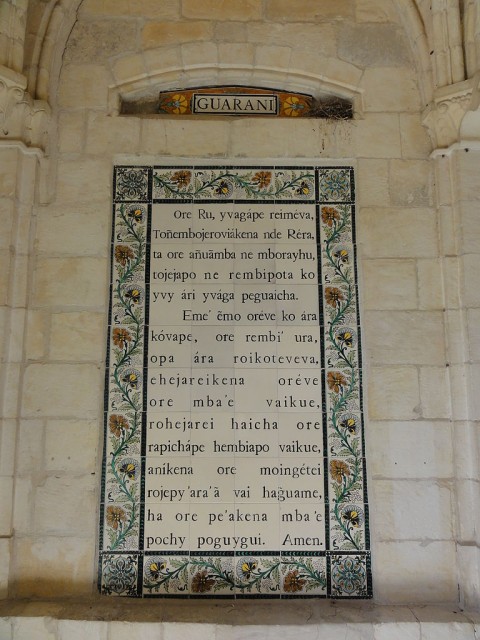

Far from imposing European languages on their converts, the Jesuits actively cultivated Guaraní and developed it into a written tongue on a par with any European counterpart. Jesuits invented and adapted words to make Guaraní more relevant to the contemporary world and specifically to the needs of Christianity. They systematically promoted this “copious and elegant” language through books, tracts, and sermons. A Guaraní Catechism was published in 1630, a Treasury of the Guaraní Language in 1639. In no sense did this activity “invent” the modern language, and there would always be multiple competing dialects. But the Jesuit impact was immense.

By the 1750s, the missions faced existential crisis. Both Spain and Portugal coveted the vast and prosperous holdings, and a series of wars devastated the reductions and forced many to be abandoned. These events are retold with fair accuracy in the 1986 film The Mission. Meanwhile, the Jesuit order itself was approaching terminal crisis. Through the mid-18th century, it came under increasing attack, seen as the enemy both of the Enlightenment and of the new absolutist politics. In 1767, Jesuits were expelled from Spanish possessions and were wholly suppressed in 1773.

The destruction of the missions was a political and cultural catastrophe. The physical buildings themselves stood little chance of surviving long in the extreme jungle environment, but two missions have left wonderfully extensive traces: La Santísima Trinidad de Paraná and Jesús de Tavarangue. UNESCO classifies both as World Heritage Sites.

The most serious effects, of course, were felt by the native residents themselves. Over 100,000 Catholic Guaraní people were dispersed, carrying with them memories of the Jesuit system and its linguistic consequences. Their descendants played a potent role in the region and were mainstays of the resistance against both Spanish imperial rule and Spanish-speaking elites.

In the new state of Paraguay, Guaraní became a symbol of patriotism, nationalism, and sometimes an assertion of loyalty to successive dictators. The language thrived, and it has perhaps 8 million speakers today. Only 5 percent of modern Paraguayans identify as indigenous, but Guaraní is the normal medium for 90 percent of the population, both mixed-race people and those of wholly European stock. Some 250 years after the crushing of the Jesuit missions, Paraguay follows overwhelmingly in the Jesuit missions’ tradition of the Catholic faith and of the Guaraní language.

A version of this article appears in the December 20 print edition under the title “Why people still speak Guaraní.”