National Cathedral unveils portrait of Matthew Shepard

Washington National Cathedral unveiled a specially commissioned portrait of Matthew Shepard, the gay college student whose 1998 murder sparked a national outcry against homophobic violence, on December 1, which would have been Shepard’s 46th birthday.

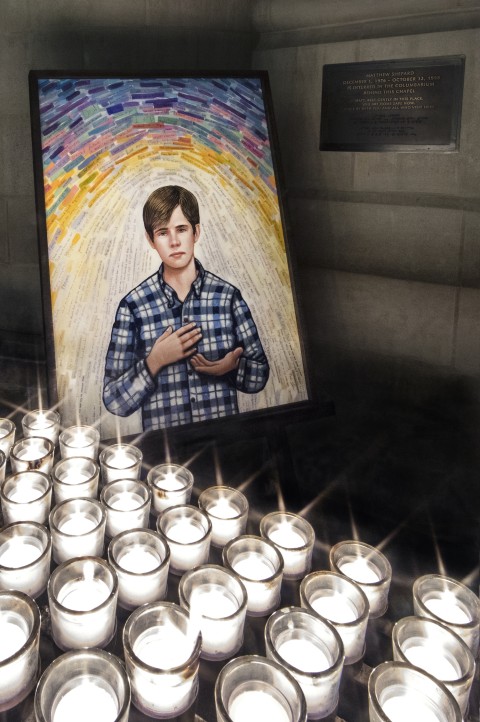

The portrait by Episcopal iconographer Kelly Latimore is on display in the cathedral’s crypt, where Shepard’s ashes were interred in 2018, 20 years after his death. Commissioned by LGBTQ+ members of the cathedral staff, it was dedicated with prayer services in the morning and evening that honored Shepard’s life and the transformative cultural legacy of his murder.

Latimore has gained international acclaim for his traditional icons of modern figures from Dietrich Bonhoeffer to Marsha P. Johnson, as well as his paintings that depict the Holy Family as refugees. But this work was different. Working with input from Shepard’s parents, Latimore depicted him without the golden halo used in his icons. Instead, Shepard is surrounded by a multicolored tapestry of written prayers and letters of support that his parents had received over the years.