Mary, mother of Jesus, returns as an icon for pop stars and activists

In recent months, rappers Lil Nas X, Bad Bunny, and Princess Nokia have all helped to spread a craze for Mary, mother of Jesus, by wearing designer Brenda Equihua’s splashy coats that commonly feature the Virgin of Guadalupe.

Of Mexican American heritage, Equihua equates the Virgin of Guadalupe with home. But there’s something deeper than simple nostalgia going on in her designs. “Wearing Mary in a fashion piece is unexpected,” she explained. “I think what’s cool is taking something out of context.”

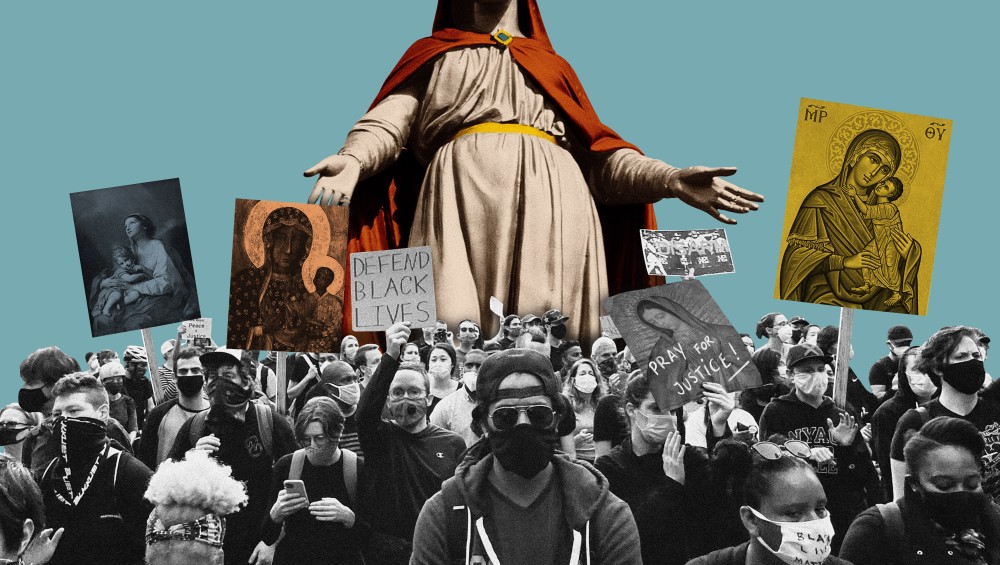

Religious figures are often (if scandalously) appropriated outside sacred settings, but the decontextualization of Mother Mary has been in hyperdrive lately. She’s treated as a feminist beacon by people of all faiths and no faith alike, her likeness appearing alongside those of Frida Kahlo, Joan of Arc, and Ruth Bader Ginsburg.