Historic Los Angeles church, once an activist hub, seeks new life

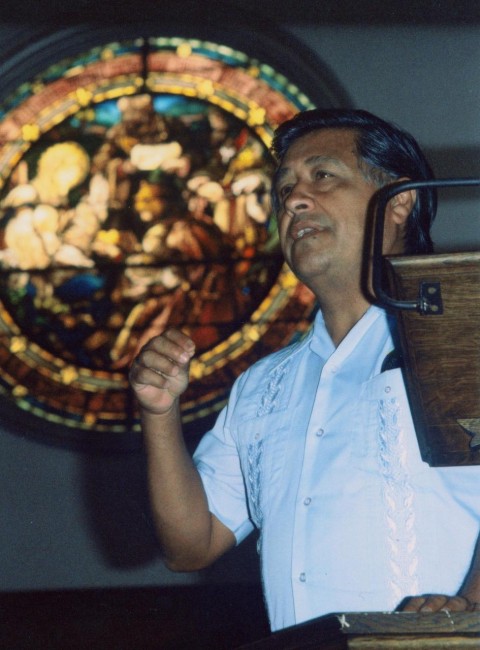

César Chávez once preached at the church, which supported Chicano civil rights organizers. But the church wants to do more than preserve its past.

Carlos Muñoz Jr. spent much of his youth at Church of the Epiphany, an Episcopal parish in the East Los Angeles neighborhood of Lincoln Heights. But he’s not—and has never been—Episcopalian.

An organizer with the Chicano civil rights movement of the 1960s, Muñoz and other student leaders held meetings at the church. It was there that Muñoz planned the 1968 student walkouts, the first major mobilization of Mexican Americans in Southern California, in which tens of thousands of high school students left their classrooms to protest racism and unequal conditions in their schools.

Mexican American activists also met at the church to plan protests of the Vietnam War, start a bilingual newspaper about movement activities, and form the Brown Berets, a group modeled after the Black Panthers. The building served as the East Los Angeles campaign headquarters for Robert F. Kennedy’s presidential campaign and the Los Angeles base for labor leader César Chávez and the United Farm Workers.