Gender pay gap among Episcopal clergy shrinking but persistent

In 2001, when the Church Pension Group first started publishing differences in average compensation between male and female full-time Episcopal clergy, men earned 18 percent more than women. Nearly 20 years later, according to the most recent CPG report, the gap in median compensation between male and female clergy is 13.5 percent.

The primary factor in the lingering clergy gender pay gap is the shortage of women in higher-paying senior positions, according to both the data and the observations of diocesan leaders.

“If you look at it from a simple mathematical standpoint,” said Mary Brennan Thorpe, canon to the ordinary in the Diocese of Virginia, “the biggest lifter of average compensation, the fastest way to get there, would be for female clergy to be called to large churches, to be rectors of large churches, which compensate more highly. And yet, there’s still some resistance on the part of some parishes.”

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

The current makeup of domestic clergy in the Episcopal Church is 60 percent men and 40 percent women. The 2019 median compensation for all domestic clergy was $76,734; for men it was $80,994, while for women it was $70,772.

The Episcopal Church has identified closing the clergy gender pay gap as a priority and has devoted resources to that end for over a decade.

In 2009, the church commissioned Called to Serve, an extensive report on the differences in compensation and vocational well-being between male and female clergy. In 2018, the church’s general convention passed a resolution that removed references to gender and current compensation from clergy files in the denominational office that facilitates clergy searches, as a way to ameliorate discrimination in the first phase of search processes.

Another resolution passed that same year, establishing a task force to examine sexism in the church, including its effect on clergy compensation.

Some dioceses have initiated local efforts to close the gender pay gap, including identifying points in the search and hiring process that are vulnerable to discrepancies—and then following up with congregations to ensure female clergy are paid the same as their male counterparts.

“I think these things are making a difference in our church, and we’re seeing it,” said bishop of Georgia Frank Logue. “It’s just agonizingly slow.”

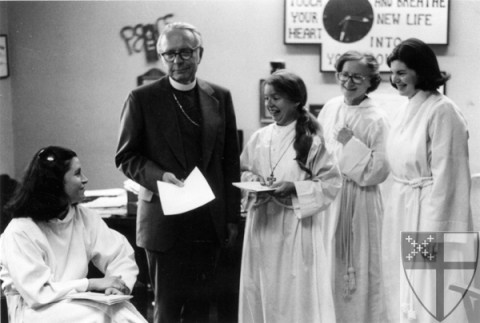

Although women have served as Episcopal priests since 1974, many people who serve on search committees grew up in a time when female priests were rare.

“I do believe that probably all churches but certainly the Episcopal Church has an ingrained model of what a priest looks like, and that model is male,” Logue said. “If a church is not considering women candidates, they are missing out on what God may be trying to do in our midst.”

In the Episcopal Church, parishes with annual operating revenues of over $350,000 are served by 1,329 men but only 780 women. But even when comparing clergy who work in similar roles or comparably sized congregations, or who have the same amount of experience, men still earn more across the board, according to the CPG report.

Those larger parishes tend to have less turnover in senior positions, which means fewer opportunities for women to advance, Logue said. And since there are relatively few of them—4 percent of Episcopal churches have an average Sunday attendance of 300 or more—that influences the overall trend.

Elizabeth Easton, canon to the ordinary in the Diocese of Nebraska, also identified salary negotiation as a crucial point in addressing the pay gap.

“We’ve learned through studies in the secular world that compensation negotiation is a lot of where this wage gap comes from. And that negotiation is just a bias minefield. How we negotiate as women, and also how our negotiation is interpreted by people—it’s sort of a lose-lose situation.”

Her solution: a diocesan policy that sets a compensation package for every position as soon as the position is posted. It’s important “to give search committees clarity about, if you will, what the marketplace is right now,” she said. “That for a position for a church in this diocese, with this Sunday attendance, this revenue level, this is what people are getting paid for those positions.”

When he was canon to the ordinary in the Diocese of Georgia, Logue made closing the gap a priority, as did Bishop Scott Benhase. The diocese began publishing an annual survey of compensation for priests, listing them not by name but by congregational size, budget, and years of experience.

Logue then identified priests who were paid much less than their peers and either worked with their vestries to establish a plan for more appropriate pay or helped the priests move to a parish that could pay them appropriately. Within four years, the median pay for male priests increased 8 percent, while the median pay for female priests increased 20 percent, adjusted for inflation, according to Logue.

Other dioceses have followed this lead, publishing annual reports of all clergy salaries—including details on the kind of work they do and the kind of churches they serve, but not names or genders.

There are cultural factors that can help, too, like having a female bishop or more diverse search committees. Even so, Thorpe said, seeing the effects of those changes takes time—and a lot of patience.

“It seems like in 2021, we shouldn’t have to be fighting this battle. But we still have to be fighting this battle,” she said. —Episcopal News Service