My incarcerated nephew, the guest of honor

Our family reunion in Argentina looked like something straight out of one of Jesus’ parables.

I’m an only child, while my husband, Gregorio, is one of 12 children. We decided to compromise and have two children. They have no cousins here in the United States, but in Argentina, where my husband is from, they have dozens.

So last summer we flew to Buenos Aires to spend time with family.

Every day we left our hotel in the city—with its grand avenues, gorgeous 19th-century architecture, and chic stores—and drove until we hit the rutted dirt roads where our family members live. We always knew we were close to their homes when our eyes began to water and our lungs began sucking in smoke from the piles of burning trash that appear on every side. The government does not feel compelled to collect garbage in these outlying areas, home to many who work to keep the city center polished.

But the stink of polluted air was quickly overcome with the aromas of grilling beef, chicken, and chorizo sausages as various family members hosted us at one celebratory meal after another.

At each place it was the same—hugs and kisses, joyful tears, and yerba maté, the ubiquitous Argentinean tea you drink from a gourd through a silver (or silverish) straw. We caught up on news, shared stories and pictures, and took selfies. I was relieved that everyone embraced our daughter’s wife as one of the family.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

Makeshift outdoor tables were set up to seat a crowd of 40 to 50 people. Hopeful dogs and hungry children hung around the fire waiting for the first tastes. At last platters of green salad, potato salad, and bread were brought out, heralding the main attraction—meat hot from the grill. After eating it was time for soccer. One advantage to such a big family is that every group we visited could field several teams and a large cheering section. The games would take place right where we were, in a dusty yard or a short walk away.

This was the pattern every day until the day we were heading out to our nephew Hugo’s home. Hugo had told Gregorio that there would be a special surprise, and as we drove we wondered what the surprise could be. It turned out to be Hugo’s brother, our nephew, Claudio.

Until then we were the main attraction at these feasts. My husband, Gregorio, is the son who made good, the golden boy living in New York, the city of dreams. I know members of his family don’t understand how money can be tight for us citizens on an island of wealth and why we can’t all fly to Argentina every year. But when we are there with them, the joy of reunion outweighs all else.

Now, however, we were going to be upstaged and the spotlight would shine on Claudio. I saw people hugging him repeatedly, patting him with love, stroking his face, kissing him, and making sure his plate was loaded with food and his glass filled. Why this special attention for Claudio?

Claudio was not a son who made good. He was home on a visit from prison, where he’s serving a sentence for a murder that happened when he was 20. He may or may not have killed in self-defense. He may or may not have taken the full burden of guilt to spare his younger brother, who was with him that night. The details of the event were unimportant during this visit.

His seven-year sentence would be over in a few months. In Argentina, an inmate in his final year of prison gets to go home on monthly visits. The first visit is for 12 hours, the second for 36 hours, and the next for 48 hours. Claudio had scheduled his two-day visit to coincide with our time there.

These visits are unaccompanied. The inmate is expected to get back to prison on time, on his own. If he doesn’t, his sentence is extended. That’s enough of a deterrent to make the policy work. The visits help people reconnect with family on the outside and adjust to life after incarceration. This approach makes sense and shows that prison reform is possible. I remember living in Argentina under a dictatorship, when a sentence to prison meant that you disappeared at the bottom of the ocean. I was deeply impressed by this change.

I was even more impressed by the community gathered around my nephew, a group that seemed to have emerged straight from a parable of Jesus. Two people were missing eyes, one due to a fight and one due to untreated diabetes. One person needed a cane to walk, while another sat in a rickety, homemade wheelchair. We were seated at the table with “the poor, the crippled, the lame and the blind,” and the burnished place of honor belonged to Claudio.

Prison has changed Claudio. He is no longer the cheerful, outgoing, funny boy I remember from a previous visit. He is withdrawn and traumatized—so our family told me as they lavished him with love. When I asked Claudio about his experience inside, he didn’t want to discuss it. “I’m surviving,” was all that he said. And then, lifting up his downcast eyes at the people around him, he said, “This is what matters.”

This is what matters at the cross, where the last become first, the margins become the center, and we are all made good through the grace of God.

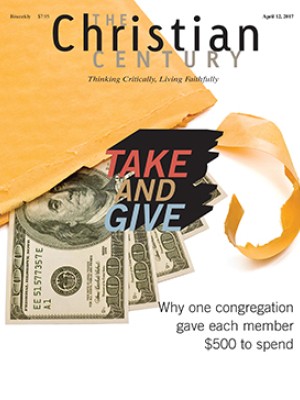

A version of this article appears in the April 12 print edition under the title “Guest of honor.”