The gifts of black youth

"Teens have the ability to do theological reflection and to connect their faith to issues of justice."

Almeda M. Wright teaches at Yale Divinity School, where she concentrates on African American religion and youth ministry. Ordained in the American Baptist Churches, she’s been a pastor and a middle school teacher. She’s the author of The Spiritual Lives of Young African Americans and coeditor of the volume Children, Youth, and Spirituality in a Troubling World.

It’s sometimes said that the current generation of African American activists is more estranged from the church than was the previous generation. Is that true?

We tend to romanticize the church of the civil rights generation. In his day, Martin Luther King Jr. got a lot of pushback from many people both inside and outside of the church. So there was not a seamless relationship between the black church and activism even then. At the same time, studies by Pew have shown that young African Americans are still very likely to be affiliated with church. And a lot of current activists are engaged in theological reflection.

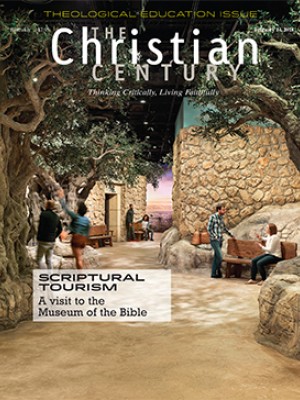

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

You’ve said that churches don’t do enough to tap the creativity of youth and to encourage them to bring their gifts into the church. Can you give an example of a how a church does that?

We’ve seen for years the power of music and dance to help young people be part of the church community. The black church has given young people a place to “live out loud” which they may not get in other places. And that opportunity is even more important at a time when public schools are cutting back on the arts.

How do you encourage leaders to be inviting to youth and to make that work central to ministry?

We push leaders to think about the places that they felt most alive when they were young and about the resources that they needed at that time. The answers tend to fall into two categories: there is the resource of people—the adults who believe in young people and are available to them—and the resource of space to gather, whether it’s in a church, school, or YWCA.

In studying African American youths, you identify a “fragmentation” of spirituality—a split between a personal life of prayer and empowerment on the one hand and a life of social activism on the other. Is this fragmentation something new or is it a long-standing feature of American Christianity?

That fragmentation is part of the American religious landscape, and it’s also a gift of modernity (and postmodernity). We all live with that sense that our lives are divided into different parts. This fragmentation can be functional: it can help us navigate the world.

What’s needed is to close the gap between the different parts of our lives. I don’t speak about an integrated spirituality as much as an integrating spirituality, because this is ongoing work, not a onetime event. What we often mean by spirituality is an integrating force, the ability to see the connections between ourselves, the world, and the divine.

In The Spiritual Lives of Young African Americans, you highlight the case of a young woman named Kira who is able to express joy in the midst of suffering and strives to make her life a witness to the truth. Why is she such an important figure for you?

Kira made me rethink a lot of my bias as a progressive Christian. Her faith in God was not something she picked up on Sundays and then put down. Life after death was very real to her. She had a certainty about her convictions. That approach can often go wrong, but her faith gave her the confidence to act, to do what she knew God wanted her to do. Because God was so real to her, there was no way she could sit still. She talked about how if we want God to move in our lives, we have to “take the limits off” our life.

At times I challenged her, and at times I wondered if her faith was a kind of pie in the sky. But I saw that it supported a robust way of living now, not simply in the future.

What do you take away from that encounter with Kira?

The first lesson for me is to pay attention to what youth are bringing to the table.

Kira pushed me to see that teens have the ability to do theological reflection and to connect their own faith—whether it’s liberal or conservative—to public issues of justice. The second lesson is the importance of helping young adults develop their theological claims and leadership skills.

Did your own experience of church as a youth shape your sense of what church can be?

I try not to romanticize the small Baptist church I grew up in. I know it was something of an anomaly then and can’t be replicated. What I experienced was a church that created space for young people and trusted them to do things. There were adults at church who believed that I had something to contribute and who worked with me to make sure I could do it. In a sense, I was thrust into leadership.

Growing up, we attended a lot of meetings of the local association of Baptist churches, and I remember being asked at the age of 12 to serve as an assistant secretary of the association. There was an older lady who said, “I can train you to take notes.” I learned that participation by youth was not only celebrated but required by the community.

I think that experience is why I remain hopeful about churches. Churches have not been a dominant influence in the lives of young people for a while, but I don’t think we need to relinquish our place. Instead, we need to claim and renarrate the importance of what we do. We are part of helping people make a difference in the world through their connection to God and to the community. We can talk about the importance of developing kids’ self-esteem, but there’s a real need to believe that there is something beyond yourself that is working with you and encouraging you forward.

If you had one sermon to give, what would it be?

It would be about loving teens and their parents. We must offer them a tough love that meets them where they are and pushes them to develop into the fullness of who God has called them to be.

A version of this article appears in the February 14 print edition under the title “A space for the gifts of youth.”