Eastern wisdom for Western Christians

“Looking east can free us a bit from our anxiety or ecclesiastical culture wars or general air of being panicked and overstretched.”

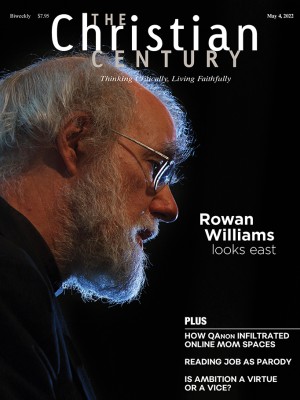

Rowan Williams presided over the Anglican Communion as archbishop of Canterbury from 2002 to 2012, during fractious, fracturing times. Now retired as master of Magdalene College, Cambridge, he recently moved home to Wales, where he engages his many commitments in the wider church at a lower profile, though his work as an academic, a prolific author and lecturer, and a well-regarded poet continues unabated. Like Augustine, one figure to whom his mind has continually returned, Williams is known for the questing spiritual fervor that undergirds and deepens his intellectual prowess.

In his latest theological work, Looking East in Winter, the quintessentially Anglican leader looks with respect and even longing toward the riches of another vast Christian stream. He explores the rich resources for spiritual practice from the Eastern churches, the Jesus prayer, and Orthodoxy’s insights on the Trinity and human identity, along with social and liturgical applications. In many ways the book is a culmination: Williams’s graduate school days left him fascinated with Eastern Orthodoxy, and his doctoral thesis mined Vladimir Lossky’s theology. He shares the riches of decades of reflection with a Western Christendom that seems plagued by anxiety and angst over its calling.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

My first real exposure to your writing came decades ago with your book The Wound of Knowledge. You were writing about Augustine, anticipating what would become a cultural phenomenon: a keen interest in narrative’s power. “The light of God can make a story, a continuous reality,” you wrote, “out of the chaos of unhappiness, ‘homeless’ wandering, hurt and sin. And so nothing can be left out of account—not even the very first inklings of experience.” In your more recent On Augustine, you write that “the shaping of a sense of self is a narrative business.” How does Augustine model attention to early experiences?

Let me start by referring to one of the things Augustine says later in his Confessions: “I became a question to myself.” He encourages us to find those moments in our experience when we find ourselves strange, when we don’t quite know what is going on or what is happening in us, when we are aware that the roots of our motivation and desire are very deeply buried. He seems to be saying, Quarry those moments of strangeness and even disorientation. Get away from the tyranny of supposing that any one moment you have a shelf full of good reasons for doing the right thing.

And some of those things he asks us to examine stretch back even to childhood, don’t they?

That is one of the ways Augustine has helped us. He’s reminding us that who I am today is something I have become, and that I’m still becoming and I’m still working through what identity means. He was an anticipator of psychoanalysis in this—not as far as the theory itself, but in helping us see that early experiences that we can’t access are acting on us now.

At the outset of his Confessions we see his renowned prayer that “our hearts are restless until they find their rest in thee.” That affirms what you’ve been saying about seeing ourselves as unfinished: even at the beginning of his spiritual autobiography he tees that recognition up.

He does. Because if we see ourselves as finished, if there’s nothing more to long for, it’s as if we are blocking off a pathway toward the deep source of our being, which is God.

If we try to imagine ourselves standing on our own internal foundation, being in ourselves solid, grounded individuals, the truth is we are going to be very disappointed—because the truth is beneath and beyond. Our life opens up to the generous and creative gift of God.

Perhaps no period has riveted so much attention to confessional, personal narratives as ours has. Augustine seemed prescient in this. For him, identity was “storied,” as someone put it.

Our identity is something that always grows. What Augustine doesn’t like is the idea that somehow there’s a moment of static perfection and achievement, after which we can stop growing. Oddly enough, that’s why he’s so critical of the extreme ecclesiastical puritans of his day, the Donatists. What do they mean when they pray, “forgive us our trespasses”? Do they really not expect that they are going to be trespassing every day? So that’s part of the story: an interest in our own growth.

But Augustine looks at his life and experience and says, it’s not me who makes a story of this, ultimately. It is God who does that, because the witness of my life is God. I look at my life and I can’t make much sense of it; I can’t much see where God was in all that. But bringing it all into God’s presence, as he did, means we ask God as a faithful witness to hold it together, draw it together.

You once said in a lecture that Augustine has been caricatured as the gloomy chaplain of predestination. But of course, he had a warmer, more human side, alongside piercing insights about how driven we are by desire. “Give me a lover,” he says in one of his homilies on John’s Gospel, commenting on the rightful place of desire in a Christian’s life, “and he will know by experience what I am saying here.”

If there’s one thing Augustine is not it’s what we sometimes call puritanical, in the sense that he thinks our desires are innately evil. Our desires are all confused and liable to go in false and damaging directions. But they are not evil. As I mentioned in The Wound of Knowledge, he says that we are in some ways to be saved by affectus, that is, being touched by something, kindled by something. We sit there waiting for the light to be put to us.

With that in the background, I note how you make repeated use of the word eros in your newest theological book, Looking East in Winter. In our time and culture, as with the ancients, eros is often associated with romantic or sexual love. Yet as you use it, drawing on Maximus the Confessor and Gregory Palamas, it has a meaning at least potentially related to desire for God—and even to the intradivine longing within the Trinity, which is interesting and provocative.

Very provocative. I think this idea that there is a positive side to desire goes right back to the fourth century to Gregory of Nyssa and in his work On the Soul and the Resurrection. He has quite a bit to say about just this. Augustine also tries to make a defense of this idea that desires have a holy function and can draw us toward God.

But it’s really Maximus who is the first to develop it. The Christian wants to say about eros that it’s a kind of basic, almost empty longing, the sense of sheer yearning at the heart of us which keeps us moving. Now Gregory Palamas is being very eccentric in saying that’s true even in God. And I don’t know how literally to take him. But I think he’s arguing that there’s something in the love that happens within the divine Trinity that is so much more than just the Father rather liking the Son and the Son being fond of the Holy Spirit. Each of the divine persons, as far as we can see, is being totally poured out in the desire that the other should live, the other should be. However strange that might seem, that’s something of what’s going on.

So how do these early Eastern thinkers help us grow in our desire to grow in God?

One thing that I think comes through very clearly in Gregory of Nyssa and to some extent Maximus is the idea that this kind of desire is not something that ever reaches a terminus. It’s not an itch you can scratch. It’s not saying, “This is what I want, and this is what satisfies it.” It’s more that there is in us a deep incompleteness that is brought to fruition only with the infinite, the inexhaustible. So the love of God is not a longing that ever finds satisfaction. That doesn’t mean it never rests. But it’s always steadily blossoming.

It’s not a cause for despair but an invitation for growth, perhaps.

And that is the light in which we ought to be understanding the negative theology tradition of the East, apophatic theology. It’s not this idea that we are looking glumly and saying, “I have no idea of what’s on the other side of it.” It’s more something that’s opening out, and opening out, and opening out. So that when we think we have found a word for it the word becomes inadequate.

It’s a bit like what C. S. Lewis is doing at the very end of The Last Battle, where he imagines the new world, a world constantly unfolding itself, and Aslan says to the children, “Come further up, come further in!”

John Zizioulas would say that the apophatic impulse is not to make us discouraged or tentative but to clear out the distortions so that we can ever more experience the fullness.

That’s right. The words we use are not an attempt to label the divine reality. They are the words we use to keep ourselves moving and to keep ourselves longing.

The Eastern idea of participation in the Trinity seems to be one of the Eastern churches’ unique contributions. Not to over-dichotomize distinctions between East and West.

I think you’re right that broadly speaking the Eastern tradition has foregrounded this rather more than the Western. And yet, going back to Augustine, he says famously in the Confessions that the divine life of heaven is not just for looking at but for living in. I think that the trinitarian force of this has to do with the New Testament idea that we are brought into the life of Jesus Christ, and that life of Jesus Christ is the life which is generated by the Spirit and turns toward the Father. If we stand where Christ stands, we are looking at the Father and are animated by the Spirit. We’re right in the middle of it.

Would you say that Orthodoxy as a whole does a better job with the Holy Spirit?

Probably, yes. That’s a difficult one. But I think so, because there’s been so strong a sense of the Spirit’s direct outflowing from the Father, a strong emphasis on the equal divinity. Eastern theology perhaps helps the Holy Spirit to feel less as an afterthought than some kinds of conventional Western theology. Which is interesting to me: lots of late 20th-century charismatics found some Eastern theologies more sympathetic to their emphases than classical Western theologies.

How has your own devotion been enriched by this perspective that is perhaps a little more strongly stated in the East?

I think probably from my earliest studies in Eastern Christianity I took this notion very seriously that the work of the Holy Spirit is to give us a share in the life of Christ and to equip us to pray in Christ and in the Trinity.

The Holy Spirit is the subject of one of the first articles I ever wrote. I argued that the Holy Spirit is the spirit of the age to come. This is what gives us a foretaste of heaven. That is why we say the Holy Spirit is at work in the sacraments and the worshiping life of the church. That sense that the Spirit is at work, for example, in the Eucharist, that’s something which the Western liturgical tradition rather lost sight of for a long, long time. It’s back now. Very much back. I’m tempted to use the slogan, It’s back, and this time it’s personal.

When I celebrate the Eucharist I’m very conscious that prayer for the gift of the Holy Spirit is there at the heart of the eucharistic prayer in a way it wasn’t with the Eucharist I grew up with. I’m struck with the way in which the new liturgies go back to the very ancient model of praying that the Holy Spirit will come down on us. So just as you present the bread and the wine on the table and ask the Spirit to transform them, so you ask the Spirit to transfigure the whole assembly that is present.

Theologian Tina Beattie argues that “the primary task of theology—like that of great art, music, and literature—is to bring us face-to-face with the dazzling darkness and thunderous silence of the trinitarian God who is incarnate within the visceral and fleshy depths of our own humanity.” How does the Trinity help us with this idea of the visceral and fleshy depths of our humanity?

I think you go back to the New Testament and think of what it meant for Paul to say in the community in Corinth that they have the mind of Christ. He’s telling them that the Spirit they pray for and invoke and talk about is the Spirit who is liberating them to call God Father. And if they are calling God Father, they are having the attitude to the ultimate source of all things that Jesus has there standing in that place. So far from God being somebody on the long end of a long ladder that you have to start climbing, you are already scooped up into it.

And I think of those small shopkeepers and slaves and women and children gathered in some backstreet in Corinth in AD 50 or so being told, “God is not somebody who lives in the temple at the end of the road and you have to keep him happy and get past by being polite. Neither is God immeasurably the distant abstract source of all being. God is pouring his life out all around you. His breath, his active Spirit, is equipping you to speak the words of the eternal words.” There they were—a slave, a shopkeeper, a woman, a landowner, perhaps a homeless beggar—being told, you live in this reality now. I’m not surprised that people wanted to be part of it.

People still want to be part of it. The tragedy of Christian history is the amount of effort we have spent trying to push God back up to the top of the ladder.

In his book on your theology, Christ the Stranger, Benjamin Myers suggests that Karl Barth begins with the doctrine of the Trinity and then spends “the rest of his life figuring out the implications.” You, by contrast, Myers suggests, begin “rather modestly, with the puzzles of ordinary human relationships,” yet you too end in the mystery of the Trinity. What did you think of that characterization?

It’s probably not too far off the mark. But I would guess Barth is answering different questions in a different age. The problem Barth is most conscious of is how to get beyond the theology that built up from human experience to speculate about the Divine. Barth wants to say, forget about building up and speculating. Something has happened, which is the revelation of the Trinity, and we’re all trying to catch up with it. I wouldn’t disagree with that for a second. But I don’t think that’s necessarily opposed to what I’m trying to say about keeping the sense of our own mysterious complexity in dialogue with the mystery of God’s relations. I’m certainly not wanting to go back to a pre-Barth position of saying that if we look enough at human beings, we’ll get some idea of God. No! That’s really not how it works.

It’s back to Augustine’s idea of paying attention to those moments when we find ourselves strange. God engages with us, takes an initiative with us, invites us, prompts us, prods us, and disturbs us. As that disturbance in us spreads through our own self-awareness and our own narrative about ourselves, we make the connection a bit better to how God works with us. And in that primal soup of interaction, the insights about the Trinity come to birth. They keep on coming to birth. They don’t come once and for all. I think anyone who has ever reflected on this will realize there are moments where you think, I’ve never understood this doctrine. I’m starting all over again.

Please say more about the title Looking East in Winter. You mention how the image comes from Diadochos of Photike, who wrote in the fifth century about how with the sun in our faces and a chill on our backs “the climate and landscape of our humanity can indeed be warmed and transfigured.”

I was very struck by that image of looking east in winter because it seems to me to say something very important about the spiritual life generally. We may still be in a wintry environment, and yet we know the sun is coming up somewhere. The resurrection happens. I guess it struck me as such an interesting image for how the Christian West might look at the Christian East.

When people look at the Christian West these days as a whole they often see a standoff between so-called liberal and traditionalist positions. They see churches wrestling with practical problems like evangelization and keeping together a very diverse and quarrelsome community. They pick up a lot of that anxiety from the church. And I wanted to say to the church, rather ambitiously, “What if you just looked at something else? Because so many people come to faith by watching somebody else looking into the mystery.”

They look at the life of Dorothy Day or Desmond Tutu or Mother Maria [Skobtsova, a 20th-century Russian monastic mentioned in the book], and they say, whatever’s going on there, it looks as if they are looking at something or someone. And to look at such a vastly rich and complicated and resourceful Christian tradition, such as that of the Eastern churches, someone might ask, “Well, what is it, who is it, they’re looking at?” Such looking to a whole tradition can free us a bit from our anxiety or ecclesiastical culture wars or general air of being panicked and overstretched in the Christian West. Why not just look into that mystery and share the patient gazing for a bit?

A version of this article appears in the print edition under the title “God’s life all around.”