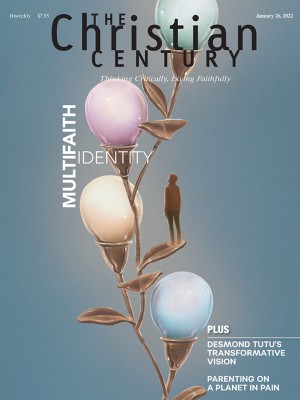

Baptist and Buddhist

Stuck in the throes of a chaplain’s crisis, I leaned on the everlasting arms while consulting the ancient dharma.

When I worked as an on-call chaplain at a level 1 trauma hospital, I almost never slept through the night. Whether it was a call to keep a lonely patient company or a call to sit vigil with a family as they watched their loved one take her last breaths, there was always somewhere to be. To be honest, this was the kind of call I would hope for—a quiet, calm call where the emergency was not so much about being the anchor in a human drama but rather about gracefully meeting an inevitability of our human condition. Loneliness. The death of an elder. The inverted blessings of being alive.

One summer night in 2015 I got the other kind of call. The kind that, despite your training and your supposed groundedness in faith, makes your stomach seize.

“We need you down here,” I hear. “We have a gunshot victim in the Brady room, and the family’s here.”

Once you cross the threshold from hospital patient to hospital staff, you learn the coded language these institutions use in conducting the business of fixing and failing to fix human bodies. Part of a code’s function is to save time. Saying “Brady room” is faster than saying “bereavement room.” But, I knew, having observed the wear that accumulates when dealing with the literal guts of human life, that this was more than just shorthand. It was a euphemism designed to create distance from the truth that, in this case, someone’s son, someone’s husband, someone’s brother was lying dead in a cold and gray room, waiting to be claimed by his given name, which was not Brady.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

Before going to talk to the family, I check in with the emergency room receptionist to see what else I can learn first.

“Can you tell me anything about what happened?”

“All I know is that he was involved in some kind of drive-by and that his girlfriend and sister are in the waiting room.”

“OK, thank you.”

Knowing barely more than nothing, I approach the door. I can hear sobbing and gasping words from the other side. People trying, no doubt, to make sense of a violence that resists the saving graces of sense. People doing the things that I have seen people do time and time again when some crisis ruthlessly interrupts their lives—running through the lists of people who need to be called, trying to remember if they have turned off the TV and locked the door before their panicked rush out of the house, figuring out who would go feed their dog—picking up the pieces of a life left lying broken on the floor. I take a breath, gently knock, and walk in.

For the next two hours I shake hands; I pat backs; I learn the variously tangled and concentric circles of relationship at the center of which lies one, now dead, man. I meet his girlfriend and his sister. I take them back to the Brady room so that they can see that it isn’t all just a bad dream. Holding hands, we gather and pray. From them I learn that this man also has a wife who’s on her way, along with his mother. I acknowledge to myself the oddity of learning from his girlfriend that his wife is in transit to pay her respects, but there’s no time or legitimate reason to inquire further. I share my condolences and say good-bye.

Moments later I welcome his wife and his mother. Shake hands and hug. We pay our respects and pray. As I escort them out, I see, just beyond the emergency room entrance, on the other side of the street, a massive crowd gathering up and down the block.

“A curbside vigil,” the former police officer who now works as the emergency room security guard tells me. “The whole neighborhood gathers to pay their respects.” Before long, people start to disperse all at once, as if some event, whose schedule only they know, has ended.

I check in with the hospital social worker to see if any other family members are on their way. Not that she knows of. I check in with the receptionist again and let her know that I’m available if anything else comes up. I go back to my room and try to sleep.

But I can’t. When I close my eyes, I can still see their faces, the waves of people who loved this man and shared with him private histories and secret jokes. I can still hear their cries. I can hear the words I prayed, wondering if they were the right words, if they were words that could meet grief—not to fix it but to reveal it and share it, with loved ones and with God. I lie there and see the prior two hours cycle through my mind’s eye. I’m not so much reflecting on the events as I am pummeled by them, an unrelenting stream of experience replaying itself without my consent and despite all my efforts. Stuck in the throes of a chaplain’s osmotic crisis.

I meditate. In the years leading up to this night, I studied and practiced Buddhism. I sat zazen with monks in a Detroit Zen center. I practiced tonglen alongside Shambhala students who had read just as much Pema Chödrön as I. I started every morning with ten minutes of mindfulness. So I think, as I lie on my cot, meditation will help me. I try counting my breaths. I try sending loving-kindness to every face that comes into my mind. It helps, but the cycle spins on.

I pray. In the years before the years of Buddhist study and practice, I was raised Baptist—both by the first church I ever attended and by the culture of the southern city in which I grew up. I call on God to comfort the family and friends of the man who, by that time, is most likely lying in the steel-clad hospital morgue. I ask God to bless the man’s soul and usher it peacefully home. I ask God to calm my spirit and bring me peace. This helps too, but the cycle keeps going.

There I am, caught in a torrent of experiences that have clearly thrown me, and all I can do is hang on for dear life to what I know, what I believe, and what has formed me. In one moment, I am a practitioner of a nontheistic spiritual discipline oriented around the teachings of a wise man who lived, taught, and died. In the next, I am a born-again believer, invoking the power of intercessory prayer to a God-man who lived, died, and rose again 500 years after the Buddha. There I lie, leaning on the everlasting arms while consulting the ancient dharma.

One summer prior to this I spent two months sharing 300 acres of Ozark forest with five monks, three dogs, and about a billion ticks. A small Cistercian monastery had brought us all together. I swept floors, weeded garden beds, and read a whole lot of books on Buddhist and Catholic spirituality. One day after morning prayers, one of the monks saw me with a book by Suzuki Roshi.

“So, are you Buddhist now?” he asked with a teasing chuckle.

Given that we spent the majority of our days in silence, there were few opportunities to get to know each other. When the moment finally arrived, I pounced on it. “Well, I think there’s a lot to be learned about prayer and the inner life everywhere. Don’t you?” I replied.

“Oh, sure. I know Suzuki Roshi’s work well,” he confirmed as he took the book out of my hand. Then, as he searched the page I was reading, he said this: “Ya know, everybody’s trying to get to the other side of the river. We’re just using different boats. Buddhism is a boat; Christianity is a boat. We can learn about other boats, sure. But, the thing is,” he looked up from the page, grabbing hold of my gaze, “at some point, we’ve got to pick a boat.” With that he handed the book back to me, saving the page that I was on, and walked away.

At first, I was astounded by this monk’s open, basically universalist approach to understanding the variegated endeavors of religion. But then— and in the years that followed—I fretted about which boat I would choose. Trusting this man who had dedicated himself to understanding the subtlest twists and turns of the inward journey, I wondered, at times toiled, about which boat I should finally and definitely commit myself to. Which design would I decide was best suited to me, my personality, and my most closely held beliefs? In which boat would I invest my hopes of making it across the river to discover whatever it is that lies in wait on the unknown shores?

These questions came to a head in the unexpected crisis that followed a night of caring for grief-stricken strangers.

Crises often have a way of clarifying things. Their force and speed push us to eliminate that which is extraneous and interrogate everything left behind. Whether we are at the center of the crisis or doing everything we can to be pastorally present at its periphery, crisis has the capacity to transform entire histories, if only for a moment, just as it upends them. Setting aside the live grievances between a girlfriend and a wife, say, as they come together to mourn the man they loved. Provoking an entire community to forget their neighborly disputes as they gather to stand vigil for a person who belonged to them. Revealing the truth of what we believe and who we are, as we try to make our way from the emergency room to our bedroom.

Lying on my cot, cycling through the grief and trauma that had been absorbed into my body, I thought about the monk, about my deferred boat-choosing. I thought about whether this might be the time, finally, to stop meditating or to stop praying and just do one or the other.

But the weight of what I had absorbed pushed the monk’s instruction out of my mind, and I returned to my Buddhist practice and my Christian prayer, the mooring stakes I had intuitively grabbed. As I lay there and leaned on my beliefs, two disciplines started to merge into one—not because I had worked out some sound means of theological fusion between them, but because they were both in me. My counting and sending of loving-kindness, right alongside my prayerful pleas to God—they were both mine. Rather than two divergent vessels, they were a single boat that appeared on the horizon of my crisis, ready to carry my life and all its concentric layers.

Several years later, I still meditate every morning, and I still pray to God. I still consult the teachings of the Buddha just as I reflect on the words of Christ. Ever since my crisis in faith, I no longer toil over which orthodoxy will be mine, which boat will be the one I choose. That night, and all the people who shaped it, helped me recognize that I have been rowing all the while—from Baptist to Buddhist to a boat of my own.