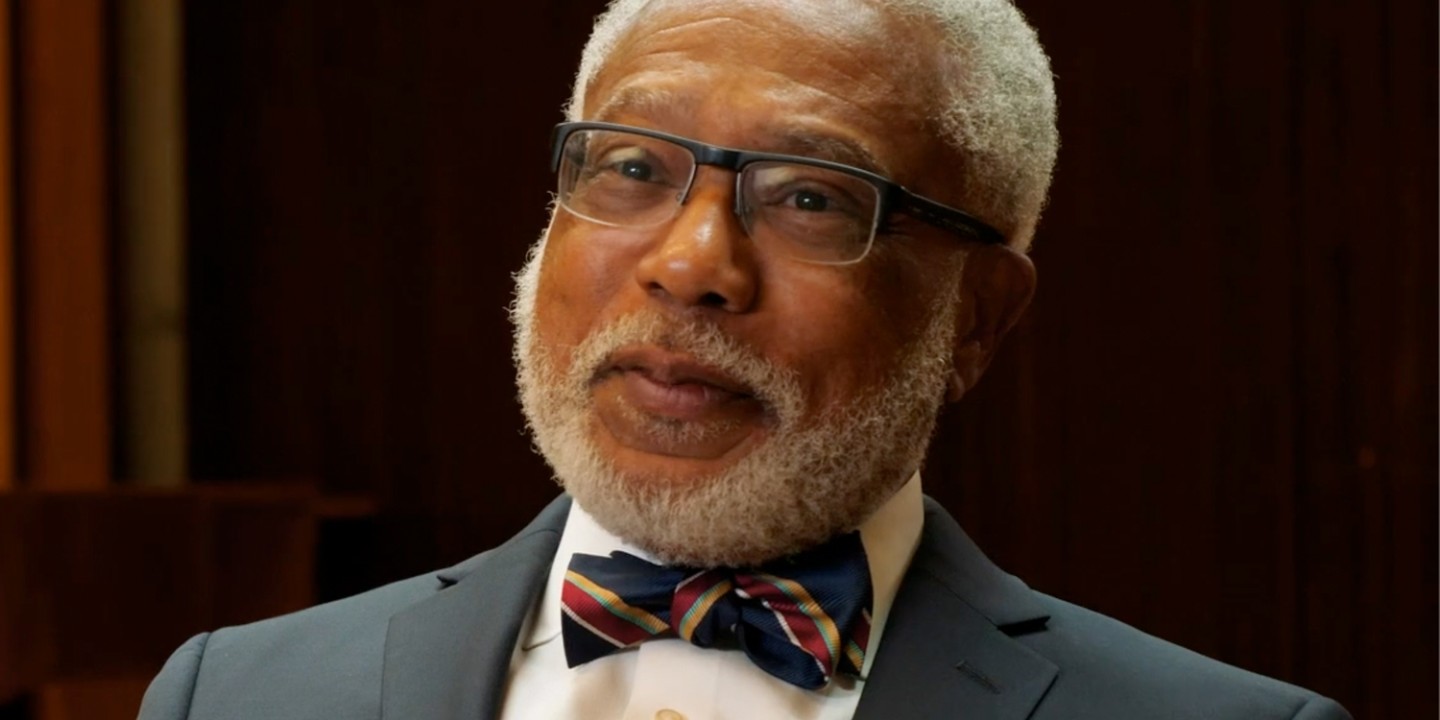

Walter Earl Fluker’s call to the Black church

In King’s time, the goal was to stir the churches to struggle. Now it’s to wake the dead.

Theologian Walter Earl Fluker (Image courtesy of Journey Films)

When Barack Obama was elected president in 2008, he symbolized the hope of a post-racial solution to the United States’s congenital anti-Blackness and racism. His election supposedly proved that established traditions of anti-racist politics are obsolete. Those who still talked about America’s anti-Blackness and racism needed to get their clocks fixed; as he said in his first inaugural address, their arguments were stale and no longer applied.

But by 2013, the political ground had shifted, yielding a movement proclaiming defiantly that Black lives matter. The reproach in this three-word message was ingeniously understated. Alicia Garza, a queer Black organizer, coined the hashtag #BlackLivesMatter along with her friends Patrisse Cullors and Ayo. Tometi after George Zimmerman was acquitted of murdering Trayvon Martin. Garza said it continued to surprise her how little Black lives matter. Many who flocked to the movement that became BLM had heard enough about Martin Luther King’s dream and were scarred by hostile treatment from White society, especially by police. Many were raised on the bromide that they had to become respectable to avert a bad future—and BLM leaders were sharply critical of the Black church’s legacy on this subject, contending that the church discredited itself by preaching a religion and politics of respectability.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

Historically, Black churches otherwise different from each other were bound to each other by the simple creed of non-racism. Their common task was to hold off the abusive racism of the dominant society. Founders of the Black Social Gospel tradition (such as William Simmons, Alexander Walters, and Reverdy C. Ransom) and subsequent Black Social Gospel leaders (such as Adam Clayton Powell Sr., Nannie Burroughs, Mordecai Johnson, and King) called on White Americans to stop betraying their American and Christian ideals. But BLM activists judged the Black church’s tradition of non-racism and argued that it undercut their agency by leaving them no real realm of action to change society.

Into this complex territory—between the defiant Blackness of BLM, the post-Blackness desires of Obama, and the anti-racism work of the Black church—stepped Black theologian Walter Earl Fluker. Fluker, who teaches at Emory University, has felt the pull of post-Blackness and has wondered about its uses and importance. But he has also reflected that post-Blackness is ghostly and shape-shifting. It is a spectral, evasive, eliding, compelling something that coerces a mode of allegiance to itself. At the same time, it undermines anything—like Blackness—that claims to be unchangeable, essential, and absolute. This represents, for Fluker, a difficulty for the Black church’s future. Should the church zero in on the Black essentialism of the BLM movement? Should it move toward envisioning a post-racial future? What is its relationship to formative figures like King and Obama?

Fluker did not agree with Obama’s 2008 assertion that America’s reality was post-racial. Throughout Obama’s drive to the White House, Fluker saw America’s racism show up in the “Kill Obama!” shouts at Republican rallies. The day after Obama was elected, Fluker described a ghost of American racism to readers of U.S. News & World Report. He said the ghost that haunts America is not the kind that spooked Sleepy Hollow in Washington Irving’s headless horseman tale of early America or the kind that stares out of staircase portraits in the Harry Potter books. America’s ghost is a cultural haunting more like the country churchyard ghosts of Black folk culture, or Toni Morrison’s ghostly central character in Beloved, conveying repressed aspects of a communal or national character.

When Obama announced that America’s long-running debates about racism were obsolete, Fluker both rejoiced and trembled at the presence of another ghost: that of post-racial deliverance. This jubilant moment in American life, he wrote, was for him “a surreal, fantastical, disembodied experience.” Fluker was thrilled at the rise of Obama, but he also found himself wondering what would be lost if the post-racial future were to become an embodied reality. What would happen to the Black church? If post-racialism is the future, how would the Black church retool its moral language and describe itself to itself? If post-racism is a good thing, as he believed, why was he so anxious? Was it merely a distrust of feelings “that were too joyful, too hopeful, and perhaps deceptive”?

Since the King era, Black Americans, Fluker argued, have been in the process of moving—or at least, should move—from dilemma to diaspora, from exodus to exile. His book version of this argument, The Ground Has Shifted: The Future of the Black Church in Post-racial America, was published in 2016, although he started making these arguments during Obama’s second term.

The King generation, he argues in this book, was steeped in the dilemma consciousness classically described by W. E. B. Du Bois in The Souls of Black Folk (1903) and by Swedish sociologist Gunnar Myrdal in An American Dilemma (1944). Du Bois depicted his split consciousness as a Black man and an American. Myrdal fixed on one dilemma: How should Black Americans relate to American democracy? Fluker does not say that the dilemma phase has been solved. He says it “still exists at the heart of African American life” but that focusing on it is self-defeating. The ethical dilemma of how Black Americans should relate to the United States’ national interests cannot be solved.

Some Black political conservatives have tied Black Americans tightly to US American national interests. Clarence Jones, for example, in What Would Martin Say? (2008), claims that King would have endorsed Jones’s support for invading Iraq and cracking down on Central American migrants. But to Fluker, Black Americans can only move beyond the dilemma problem by embracing the homeless diasporic reality of Black American existence. The first transnational modern community was the Black culture that emerged from the ships carrying enslaved Africans to their fateful destinations. By emphasizing diaspora, Fluker is able to interpret King as a global citizen.

One question Black Americans have long struggled with is whether there is an essential Black American identity to which they adhere or whether these global identities are fluid and indeterminate. While other thinkers have zeroed in on Black identity as essentialist, Fluker sides more with the indeterminacy of diasporic identities. Yet he agrees with religion scholar Dianne Stewart that if the deconstruction of race were doing more harm than good, it should be possible to suspend anti-essentialist criticism of diasporic ethno-cultural and racial identifications with Africa. Even if one assumes that Blackness is fluid and unfixed, Fluker reasons that scholarship on diasporic identity is just beginning. Diasporas are thoroughly shape-shifting, “yet necessary for navigating the world.” Black American religious communities are connected to diasporic roots and shoots across the planet “but are not ultimately determined by them.”

Moving from exodus to exile is a complementary frame that utilizes biblical categories. Drawing on two generations of womanist criticism and the Black humanism of William R. Jones, Fluker adds that if one reads the later King from a world house perspective, King’s mountaintop sermon in Memphis, Tennessee, opens out not onto the promised land of the exodus story but onto a diasporic-exile horizon—an unknown land. The promised land metaphor conjures up images of Joshua conquering Canaan and slaughtering Canaanites. In the past it worked only when applied selectively to the African American situation. Today its relevance in Black churches is rapidly diminishing, except in Pentecostal prosperity versions that turn prophetic religion on its head, converting the promise into private spiritual deliverance or worldly wealth.

Fluker warns that the spiritualization of the exodus story by a growing surge of Afro-Pentecostal, charismatic, and prosperity gospel churches has “all but erased” the social gospel in large sectors of Black Christianity. Pentecostal religion emphasizes ecstatic spiritual experience, spiritualizing the biblical emphasis on justice. Prosperity religion preaches that God wants born-again people to be materially wealthy and free of disease. Fusions of charismatic and prosperity religion have made deep inroads into Black, White, and Brown evangelical and nondenominational churches. Fluker stresses that the social gospel and liberationist versions of exodus theology are being routed in Black churches where the operative theology is that God wants the faithful to be rich and being rich is a sign of faithfulness.

The exodus motif, he contends, is like the dilemma framework in perpetuating more problems than it solves for Black churches. It evokes something real, but it does not fit the contemporary situation except when twisted into something that militates against justice and a healthy community life. Fluker says the exile frame speaks far more personally and relevantly to Black Americans today. King offered an inspiring version of it in the mountaintop sermon, taking the crowd at Mason Temple on a panoramic tour of Western history that folds the exodus event into a story about the long march of humanity toward freedom, inviting the crowd to place itself in the worldwide struggle.

The exile perspective of womanist theology, as expounded by the scholarship of Delores Williams, Kelly Brown Douglas, and Cheryl Sanders, is helpful to Fluker in making this argument. Williams points to the intra-oppressive dynamics of the exodus frame. Douglas challenges Black theologians to stop treating male heteronormativity as the norm of Black leadership. Sanders commends the Sanctified Church for rebuffing the oppressor versus oppressed rhetoric of the social gospel and liberationist traditions, which dwell too much on Whiteness. The Sanctified Church has always had an exile consciousness, deriving Black identity from the spiritual experiences and traditions of Afro-Pentecostal and holiness churches. Fluker highlights that a broad form of exile consciousness has long vied with the exodus motif for primacy in Black Christianity. Black Americans have never belonged to the United States of America, but perhaps they can find a home in global struggles for justice by people of color.

The wilderness, to be sure, is dangerous and lonely. It is hard to find a home in the wilderness and hard to be heard there. Fluker occasionally catches himself when expounding on the freedom of exiled wilderness, remembering his own considerable “privileges of academic and ecclesiastical authority.” But he gives the upper hand of moral authority to those who cry in the wilderness. Those who are driven to the wilderness do not seek to make straight that which is crooked. They do not assume responsibility for the right ordering of the world. They dare to speak for themselves, “the voices of the muted, missed, and dismissed, the wretchedly fated who have no recourse but to cry out.”

To feel one’s wild, lonely, broken, embodied, alienated, not-belonging-anywhere homelessness is to be cast from the frying pan into the fire. Fluker acknowledges that King roared against homeless alienation, preaching that he was somebody and so is every child of God. King said what mattered about him was his fundamentum, his sacred dignity and eternal worth as a child of God. But ultimately, Fluker wants to reject King’s personalism, and he sets up his rejection by misrepresenting it.

Fluker claims King’s personalism was a static philosophy based on Enlightenment dualisms of mind-body and permanence-change. To the contrary, King was steeped in the neo-Hegelian personalism of Edgar Brightman and Walter Muelder, which was not static, dualistic, or based on a substantive self. Although Fluker claims that King had to overcome his idealism to struggle for justice, King said the opposite: that his personal trials taught him the value of unmerited suffering.

But Fluker retains an important aspect of King’s fundamentum theme: the sense of embodiment enfolded in it. Somebodyness implies a crucial source for ethical living in the body. There is no ethical life or aesthetic life without a body. Ethics responds to beauty, balance, and symmetry in life, not only to questions of right and wrong. The body is an aesthetic site for pondering what it means to privilege the frames of diaspora and exile.

What this means is that Black people move from the frying pan to the fire. The frying pan is an existential-aesthetic moment epitomized in Black bodies gunned down by police, prisons crammed with Black bodies, and cities teeming with unemployed Black bodies lacking health care. The dilemma framework tells the Black body to stand still, looking for God while being assaulted. The exodus framework references a liberation that has already occurred and points to a redemption beyond the world.

But the fire, Fluker underscores, is purgative and universal. Whatever commitments that African Americans make to the nation must cohere with their commitments to all people of African descent and oppressed people everywhere. Fire is a critical tool of the Spirit that allows us to interrogate how Black bodies are held in bondage to the political-cultural, theological-ethical, and existential-aesthetic gazes of the ghost of racism— and then to look beyond them. The fire of Pentecost, Fluker observes, is spreading through the world, both in churches that bear the name Pentecostal and in churches that don’t. A corrective to forms of religious expression emphasizing facility of language and domination, this fire teaches religious communities to look for signs of blessing in plurality, novelty, diversity, and openness.

The future, on this account, is Pentecostal, whether by name or not. The question for the Black church is whether the fire will yield religious communities turned upon themselves or struggling for the flourishing of endangered bodies throughout the world.

Fluker contends that three generations of African Americans have come of age lacking a moral script. He acknowledges that some of the old scripts are best forgotten, “but when you appear on the stage of history without your lines, in most cases you appear either as an anxious stutterer or as a highly improvisational actor.” The calling of church leaders in King’s time was to stir the churches to struggle for freedom and equality. The calling of church leaders today is to wake the dead.

To wake the dead, Fluker argues, Black Christians must congregate, rally their diminished communities, conjure a better future than the one mapped out by neoliberalism and the prosperity gospel, and conspire to make a difference. Generations of poverty, unemployment, bad schools, crime, incarceration, and family dissolution have taken a devastating toll, and the neoliberal economy has no use for disadvantaged Black people. The same social and economic forces that create walled-off enclaves in the larger society drive middle-class Black churches farther from the Black poor. To wake the dead, Fluker urges, mainline Black churches must begin by confessing their complicity in pushing aside the poor and neglected.

Black faith is profuse and soulful, steeped in suffering whether theologized or not, and bent on freedom whether politicized or not. Its acquaintance with sorrow gathers religious communities at the cross, sometimes with a blues inflection, and at the Easter tomb, in the hope of resurrection. A Black social gospel tradition that includes Fluker—alongside William Barber, Traci Blackmon, Raphael Warnock, three generations of womanists, and hundreds of pastors—cannot be said to be the afterglow of a heyday. Black social Christianity, a product of Black Christian communities with an incomparable legacy, is struggling, but far from dead.

This article is adapted from A Darkly Radiant Vision: The Black Social Gospel in the Shadow of MLK (Yale University Press).