A troubling new coalition in Israel

How will Netanyahu and his new allies govern? And what will become of the Israeli left?

A few weeks before Israel’s elections, I attended a meeting in Jerusalem organized by the left-wing religious group Oz VeShalom. A panel addressing the small, liberal audience was comprised of representatives of five political parties, ranging from the radical left Meretz party to the right-wing Yisrael Beiteinu party. Each spoke for a given time, and then they argued among themselves about the best way to run the country.

One theme engaged them all: the method by which to achieve peace. No one raised the possibility that there is no prospect of peace in this region, not now nor in the foreseeable future. Neither the Israelis nor the Palestinians are prepared to give up their claims to land—it’s in their DNA. The fact that these senior party representatives, most of them members of the Knesset, could not or would not articulate this simple truth suggested that their outlook is based on an illusion or a lie. Either they didn’t see this existential reality or they were hiding from it—afraid, perhaps, that it would harm their chances at the polls.

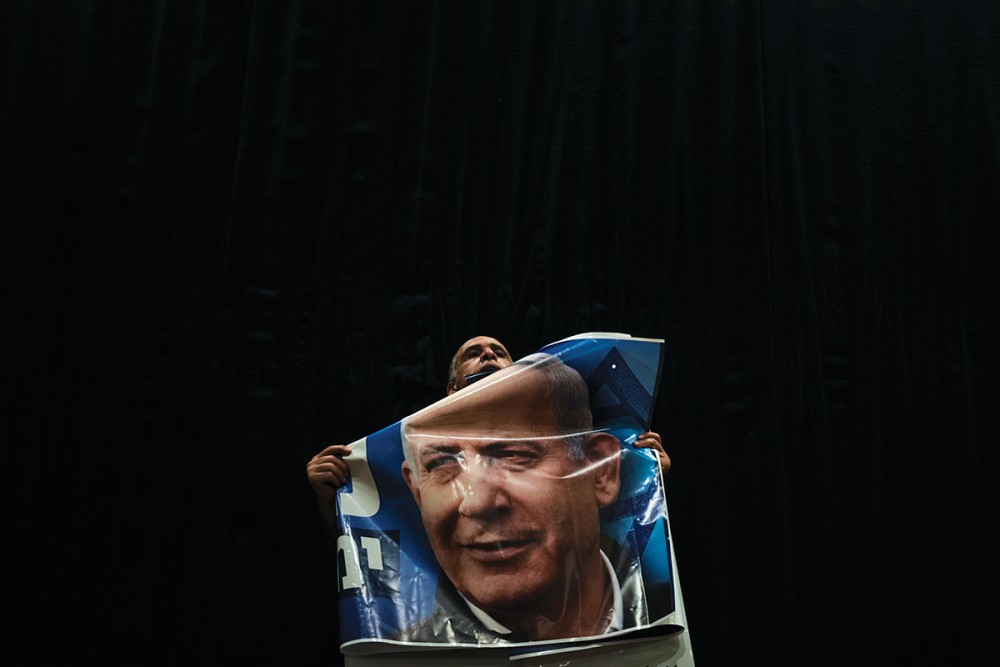

Now the elections have taken place. They were won not by any of the parties to this earlier debate but by the most right-wing groups ever to emerge as legitimate representatives of the people. The coalition is led by former and future prime minister Benjamin Netanyahu—who is mired in at least three different legal battles—and peopled by parties (the Religious Zionists, Jewish Power, and Shas) whose platforms include racist views of Palestinians and a promise to change the judiciary in order to undermine the accusations against Netanyahu.