Staying in a culture of leaving

My parents arrived in the US with three suitcases and two toddlers. I’ve experienced wanderlust ever since.

I am, by nature, a leaver. Once a relationship, job, or any other arrangement that assumes commitment gets to be challenging, I fantasize about the next, better thing I can dash off to.

The urge to move on may be in my DNA. Like many Korean immigrants during the 1980s, my parents were allowed entry to the United States through a student visa for my dad, who received admission to a graduate program in architecture at Tulane University. They arrived with a semester’s worth of tuition and living expenses, three suitcases, and two toddlers. The rest of their belongings and relational ties were left behind in South Korea, a world away. One of our first homes in the US was a cramped studio apartment where the four of us slept on one queen-size mattress on the floor. I could touch the kitchen cabinets from our bed.

Conversations about what my brother and I wanted to do when we grew up were our bread and butter, or rather, our kimchi and rice. One week, I’d dream of being a San Francisco–based journalist traveling the world; the next, I’d want to be an Ivy League philosophy professor. This dreamer spirit made my childhood fun and imaginative—our reality seemed to have no bounds. It wasn’t until my late 20s, when I was planning my wedding, that I began to feel, for the first time in my life, homesickness for a place and community I never had.

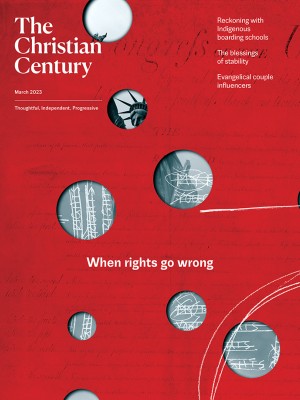

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

I wanted to get married in Southern California, where I had spent the majority of my life but with no specific home base since we moved every few years. This was hard to justify given that my fiancé, James, grew up in the same house in New Jersey from first grade to college and had significantly more relatives, neighbors, and longtime family friends there.

I wanted what he would have in New Jersey: a wedding filled with people who had known me since I was six, family friends who knew my parents before they were parents. But no matter how many photo albums I leafed through to jog my memory, the list of names came up short. I started to dream of a very different future for myself—a life where my roots would grow so deep that my wedding gift to my future kids could be a guest list overflowing with familiar names.

But my wanderlust always came back, encouraged by daily scrolls through images of friends (or strangers I follow because I wish we were friends) starting new lives abroad or new relationships that appeared more exciting than my own. It’s easy to imagine that a more fulfilling life—more authentic to who we truly are—awaits us if we leave our current situation. That’s because in this fantasy we’re never the barrier to our own flourishing; it’s our circumstances. My city’s too boring, my husband isn’t romantic enough, my work environment is toxic.

We often blame this discontent on the advent of social media, but as it turns out, our modern-day FOMO isn’t so modern. Nestled deep within the heart of a religious tradition that goes back to the sixth century is an antidote to what must be an age-old human impulse of blaming our circumstances for our dissatisfaction. That antidote is found in the Rule of St. Benedict, and it’s one of the three vows that must be taken to become a Benedictine monk: the vow of stability.

Unlike most other monastic communities, where monks are sent to different monasteries within their order throughout their lifetime, Benedictines commit to the monastic home of their formation. This vow of stability safeguards them from the all-too-familiar urge to relocate when there are conflicts or feelings of wanderlust. Through living out this lifetime vow, Benedictines bear witness to the truth that each relationship and place, no matter how old, is infinite and ever renewing—and so are our internal lives.

St. Benedict has received increased attention in recent years from authors who have found in his writing immense applicability for our hypermobile and consumer-driven lives. Esther de Waal, Daniel Grothe, and Rod Dreher each dusted off St. Benedict’s seemingly archaic rule to try to figure out how to live well in a world of infinite choice.

But I first learned about his vow of stability when I was a secretary at a seminary. The student who introduced me was hoping to become an Episcopal priest. To pursue ordination, she had to receive approval and affirmation of her calling from her own congregation. Though she had served her local congregation for many years as an usher, Sunday school teacher, Bible study leader, and much else, she was rejected for ordination by the discernment committee. They just didn’t think she was suited for ministry.

When she shared this with me with tears in her eyes, I was outraged on her behalf. I gasped, “Are they blind?! You need to leave your church pronto and begin the ordination process at another one, with a whole new set of people who will definitely recognize your calling.”

But she didn’t leave. Months passed, and she healed from the grief of rejection—both the rejection by her fellow church members and the rejection of her aspiration to the priesthood. She continued to stay at her church, taking up more leadership positions. I was amazed by her steadfast commitment to those people, and when I told her as much, she shared with me that one of the primary tenets of Benedictine spirituality, which she herself practiced as a layperson, was stability. What that meant for her was staying knitted to this group of people who still were and will always be her spiritual family.

This approach was utterly foreign to the way I had been raised—so foreign that it fascinated me. Here was wisdom that I hadn’t encountered before but intuitively identified as the path I was seeking in my quest to grow deep roots for me and my family.

Now, when the impulse to escape emerges (because it always does), I ask myself a different set of questions. Instead of Where should I go next? I wonder, What can I change within myself? Having harnessed the power of this internal shift, where once I couldn’t find true fulfillment anywhere, I can now find it everywhere. As counterintuitive as it might seem, there is powerful liberation in choosing to commit.

Wendell Berry explores the idea of commitment to place and people within the realm of economics, a field that generally assumes that our human impulse to be on the move is primarily self-serving. Once an individual feels like they have received all the advantages and benefits of a certain place or relationship, they move on to the next. We have witnessed how this has played out on a larger scale, seeing large swaths of America, both the land and its people, stripped of their resources and abandoned.

The loss of jobs and resources in rural America spurred a large influx to urban areas. What happens when people are constantly on the move, though, is that there’s no commitment or responsibility to communities and environments—which is precisely what enables the thriving of environments, communities, and, I would say, individuals.

We have also seen the reverse: readers of Berry and other proponents of localism who are inspired to leave their urban lives and get back to the land and create their own communities. But transporting oneself to an unfamiliar region and lifestyle will eventually trade one longing for change for another. The better solution, Berry says, is for most people to stay where they are, commit to it, and make it better.

Of course, sometimes staying is a luxury, and sometimes—as for refugees or survivors of abuse—it’s not an option. In the Bible, neither staying nor leaving takes clear precedence over the other. The book of Exodus is all about fleeing: the Israelites’ flight from Egypt is God’s liberating gift to them. And when they are liberated, they don’t immediately settle in a new home, not even close. They roam the desert for 40 years. The biblical writers acknowledge the importance of the journey—wandering, exploring, living as an alien in another region.

However, the journey is always meant to lead the people back home, even if they don’t return to the same starting point. Everything that happens on the way helps them renew their commitment to a people, land, and sometimes a vocation they originally resisted. They leave foolish and return wise. This is the throughline in the first Christian autobiography, Augustine’s Confessions. It’s also Wendell Berry’s story, which is the experiential basis for much of his writing on place.

In the case of my parents, immigrants in search of new lives, moving to America meant being unshackled from the rigid class systems in their country of origin. In this new land of opportunity, the question of how they might contribute to the area they were living in and the people they were living among was far from my parents’ minds. Their single, driving purpose was to escape from the suffocating demands of their families and break free from their lower-class rank in Korean society. They would move and change careers however many times it took to make that possible.

Stories of journeys are often bookended by leaving home and homecoming. But when my parents left South Korea, it was almost entirely an outbound journey. They didn’t even have in their minds that they were going to a new home, to establish new roots. They were escaping, making everything new.

Years after I took my own vow of stability—to my husband, family life, and career path as a United Methodist minister, which entails being bound to a church community—I found myself in a ministry post I hated. It was a plum package: I was the senior pastor at a large congregation in San Diego, one of the most beautiful places to live in the country. My dread was accompanied by so much guilt and self-induced shaming. How dare I be ungrateful for this golden opportunity!

Here I learned there are times when a commitment to stability must be broken. Sometimes jobs must be quit, divorces must be filed, childhood homes must be sold. Sometimes the grass really is greener on the other side. So how do we know whether we’re making the right decision to leave a bad situation or simply attempting to escape ourselves?

My impulse to leave the church in San Diego felt different to me than previous times I’ve wanted to bolt. I wasn’t escaping a difficult situation—on the contrary, it was a sweet deal all around. What I wanted was to be closer to my parents and my brother so my kids could be near their grandparents and uncle—to embed them in a tight-knit network of relatives nearby. I wanted to be a stay-at-home mom for my two kids while they were little. I wanted more time to write, a newly budding passion of mine. All of these dreams came true, and the process of pursuing these dreams has felt like a deepening of my roots—a homecoming, not an escape.

I made the decision to leave San Diego at the start of the pandemic, and finding a new place to live seemed both daunting and potentially dangerous. We ended up sheltering in place at my parents’ home—their seventh since immigrating to the United States. They bought it just as I was leaving for college in 2001, and it was unlike every preceding home in that it sat on a one-acre property and was nearly gutted before we moved in.

As often happens with my parents, who tend to dive headfirst into life, the remodel was far more costly than they anticipated. My parents drained their entire savings (including my college fund) for this house. I resented this place for years because it was the ultimate symbol of my parents’ capriciousness. The two of them could scarcely maintain the home and keep up with its infinite demands. My brother and I tried to convince them to sell it, thinking they’d prefer a simpler life, but they never budged, which I found odd, given their history.

Once my family of four moved in with my parents in summer 2020, the entire character of the house transformed. What had once felt cavernously large was now cozy. Rooms that had collected dust from disuse were now explored by tiny hands and feet or strategically used for hide-and-seek. All those years, without my knowing, my parents had been growing roots so deep that generation after generation could take refuge under their branches.

And so it is that my parents revealed to me another important element of stability: it’s never too late to start practicing it.