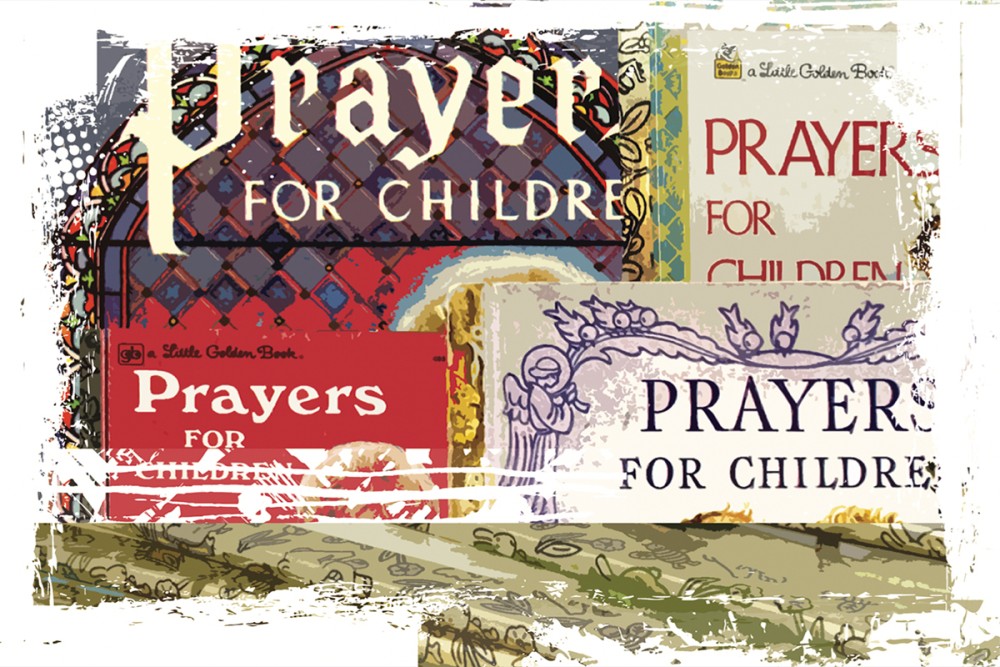

Going through some belongings the other day, I came across a book from my childhood that has accompanied me through decades of moves.

Leafing through Prayers for Children struck me as it always does for the visuals on display: the dreamy-soft focus to Eloise Wilkin’s colored pencil and watercolor illustrations, the scenes of sentimental rural calm and homey loveliness, the chubby-cheeked children.

As many times before, something in me went still as soon as I opened the frayed edges of the cardboard cover. But I realized this time how the Little Golden Book’s well-thumbed pages also hint at the ways in which prayer can leave us dry and casting about for adequate words.