AJ Muste’s Christian nonviolence

Once a household name among progressives, the activist and minister influenced generations that followed.

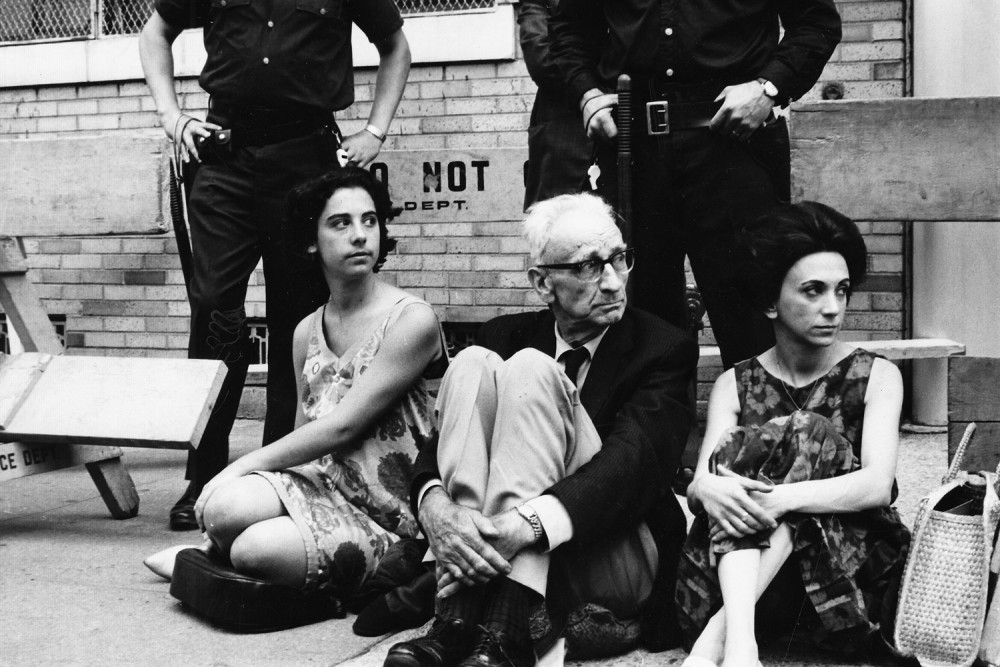

AJ Muste, center, sits with fellow activists Miriam Levine, left, and Judith Malina at the Atomic Energy Commission in August 1963. (Courtesy of the AJ Muste Memorial Institute / War Resisters League)

During a quaker meeting in 1940, Abraham Johannes Muste, whom Time magazine declared “America’s #1 pacifist,” proclaimed that “if I can’t love Hitler, I can’t love at all.”

Imagine saying such a thing about Vladimir Putin. It’s difficult, perhaps because the depth of pacifism that Muste embodied feels passé. As American weapons are airlifted into Ukraine and American drones roam the deserts for our foes, national security feels paramount.

Today, a declaration of love for Hitler by a lanky, bespectacled minister would seem a prime target for cancellation. But Muste’s wholehearted and full-bodied devotion to creative, direct action for peace and justice made him a linchpin in the peace movement and a model for generations of activists.