One afternoon during this long pandemic, several of us from church meet on the bank of a river for a baptism. A deacon begins our service with a water prayer from our hymnal. “God of grace, creator of waters, your Spirit hovered over the deep.” Her words drift across the river. The candidate and I kick off our sandals and step into the shallows. “We remember when you flooded the earth,” the deacon prays as we wade farther out. “We remember your Son, who, like all of us, arrived in the waters of childbirth.” Once we’re waist-deep, we stop and find our footing.

He leans back into my arm across his shoulders. “I baptize you with water,” I announce as I plunge his body into the current, “in the name of the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit, one God, mother of us all.” After I pull him up, as he wipes the water from his eyes, I glimpse in his face something of my own face from all those years ago—at my baptism, as a teenager, when my grandfather cradled and then dunked me. In the instant before I went under, he tilted his head toward the sky and called out over the waters, “En el nobre del Padre, del Hijo, y del Espíritu Santo.”

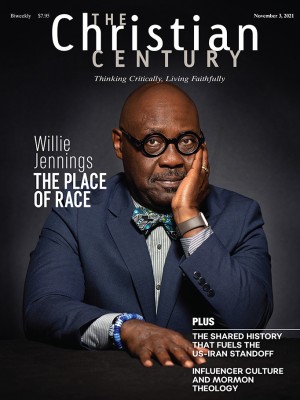

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

Through baptism, we find Christ’s life in the water. “There is one body and one Spirit,” we read in Ephesians, “one Lord, one faith, one baptism.” In the water, the Spirit draws us into God’s life. In the water we’re reborn as members of one another, a union across geographies and eras.

After the baptism, as we dry off, I notice an earthy taste in my mouth, leftovers from a splash of river water. I remember that passage late in Marilynne Robinson’s novel Housekeeping, where the narrator retells the early chapters of Genesis as a plotline that culminates with the flood, a second creation to wash away the sin and loss which have already become too much for history to bear: “Let God purge this wicked sadness away with a flood, and let the waters recede to pools and ponds and ditches, and let every one of them mirror heaven. Still, they taste a bit of blood and hair.”

The waters remember. The seas and streams have absorbed the generations. Redemption doesn’t disappear the past. Even when lakes and creeks glisten with heaven, there remains “a certain pungency and savor in the water,” Robinson writes.

At the baptism, primordial life must have lingered on my tongue. Even so, I lack a palate sophisticated enough to understand what the waters communicate—the stories passed along in the layers of rich mustiness and bright minerals in every droplet. Maybe our taste buds will evolve to decipher the language of water—if we, as a species, survive long enough.

The waters have been a witness across the span of human existence, a companion to life—an ancient flow whose cycle unites the sky above to the surface here below, a current that circulates through each of our bodies. This living thing, with us since before our beginnings, might know us better than we know ourselves—as close to us as we are to ourselves since it makes up more than half of our bodies, each of us as a blurred commingling of water and human.

In the 16th century, in Central Europe, Anabaptist communities passed around an anonymous tract, The Mystery of Baptism, which invited peasants to consider other-than-human creatures as Christ’s evangelists. “In the gospel of all creatures nothing else is shown and preached but the crucified Christ alone,” the author explains. “But not Christ as the head alone, rather the whole Christ with all his members—this is the Christ that all creatures preach and teach.” According to this theological vision, God has commissioned animals and rivers and landscapes as guides into Christ’s revelations, Christocentric theophanies, a gospel for human and nonhuman creatures alike.

Baptism is our immersion into Christ’s death and resurrection, our creaturely union with the waters as we undergo the labor of another world being born within this one. In the baptismal waters we join nature’s ache for redemption, for restoration. “Creation waits with eager longing,” Paul writes in Romans, to “be set free from its bondage to decay.”

Perhaps the savor of that river water in my mouth was the taste of earth’s longing for heaven, for a healing of our legacies of harm, for creation to be transfigured with God’s glory, for all creatures to be “united and bound together through the bond of love,” as The Mystery of Baptism declares, our belonging “with Christ, one body with many members.”

As we confront our environmental devastation, our climate catastrophe, our polluted world, we remember our baptisms as a communion with creation—our initiation into a life of solidarity with the waters, God’s primeval creature.

A version of this article appears in the print edition under the title “What the water remembers.”