Walking with Moses from slavery to liberation

When Moses says “keep still,” he’s not recommending inactivity.

I have been thinking a lot about Moses, about bondage and liberation and what it looks like to imagine one’s life apart from the lens of an oppressive regime. Somehow, Moses is drawn from a space of death into privilege, then into the wilderness, and then into the throes of a liberation movement. It’s all miracles and power and bags full of gold—until he and the Israelites hit that watery obstacle and hear Pharaoh’s army behind them.

How did we get here? I imagine this question coursing through Moses’ body at this moment. This is hardly the glory Moses might have imagined when he first heard that voice coming from a burning bush. But Moses calls out to the people with the only promise he knows: “Be still.”

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

While we might associate Moses with power and wonder, in actuality he is rather ordinary. As he stumbles into being used by God, his most evident quality might be his unknowing. But being ordinary is not the same as being without purpose or possibility. And Moses’ life has already been speaking.

You recall the story of Moses’ birth, how Pharaoh, fearing the increasing Hebrew numbers, orders all newborn boys to be killed? Shiphrah and Puah tell Pharaoh they could not get there in time. Then an unnamed Hebrew woman slides her child into a basket, hoping for some form of life.

The women in these stories love and fear their God—a God who has heard their cries, who they know desires life. In their small acts of resistance they make manifest, incarnate even, God’s presence in their midst. In their participation with God, Moses’ life is made possible. Through their everyday actions—their sly lies, their desperate acts of faith—they plant a seed of God’s freedom in the very heart of the empire’s power.

We sometimes think of revolution and liberation as Hollywood action adventures, men and women conquering evil through valiant acts of bravery. But perhaps revolution has always been enacted through the small acts that refuse to accommodate the regimes of death that press in each day.

The life made possible for Moses is not an easy one. As he grows older he is formed by the power and privilege of life within wealth and seemingly unlimited freedom. But I imagine he does not feel at ease there. At every turn he is undoubtedly reminded he is a foreigner, that his face renders him somehow outside.

What else can explain the fit of rage that causes him to defend two Hebrews one morning? To kill a “fellow” Egyptian? Maybe he feels not only the privilege of his adoptive mother but also the pain of his birth mother. Maybe he sees what the privilege cost.

Even Moses doesn’t understand what he signifies in the midst of these upheavals. He walks back into Egypt as one who should have been dead. Hidden in what should be a watery tomb, he is drawn out of the water into life. He should have been exiled, living an anonymous life in Midian, but is pulled back to Egypt to be an agent of a God whose name he just recently learned.

After the miracles and refusals and more miracles, the Israelites are amazed, walking out of Egypt with gold and food and some semblance of hope—until they see the sea and hear the rumbling of horses and chariots. They begin to wonder if slavery wasn’t all that bad. They were meant to be strangers, meant to work and toil and die. Maybe they should just accept it.

And to this Moses replies, “The Lord will fight for you, and you have only to keep still.”

Keep still? They should probably be walking. But there is another meaning to still here: to plough or engrave. It’s not inactivity but a directed, purposeful movement. Moses wants them to walk into their liberation. At this moment it’s not a question of what they should do but of who they are. Be still, God says. Plough, dig, plunge your hands into the ground and feel what gives you life. You are not slaves or foreigners. You are not what the empire tells you you are.

Be still and see that you were meant for life. Know that God has been fighting for you—in midwives and nameless Hebrew women, in prayers done in secret and meals made for the sick. Who are you? You are God’s children whom God breathed into being. Be still, and feel the center of your being and how it cries out not for the toil of Pharaoh but for worship and life with your Creator.

God tells Moses to plant his staff in the ground and the sea will part. Moses drives his staff into the ground, ploughs its depths, and in the midst of death and confinement, God reveals the possibility of freedom lying below. It was there the whole time.

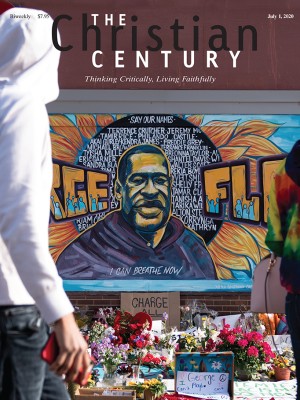

Laws might name us slaves or illegals or terrorists. The powers and principalities might try to erect cages around us or tear us from our families. But we refuse to accept these transgressions as who we or others are. We choose instead to be still, to plough deep. What emerges are sprouts of life, baskets laid in water, a still voice in a seeming desert, streets filled with bodies saying that black lives matter.

We choose to be life, in all its stubborn and mundane forms. We choose to drive our staff into the ground and see what God will do, what paths of liberation might be revealed.

A version of this article appears in the print edition under the title “Still plowing.”