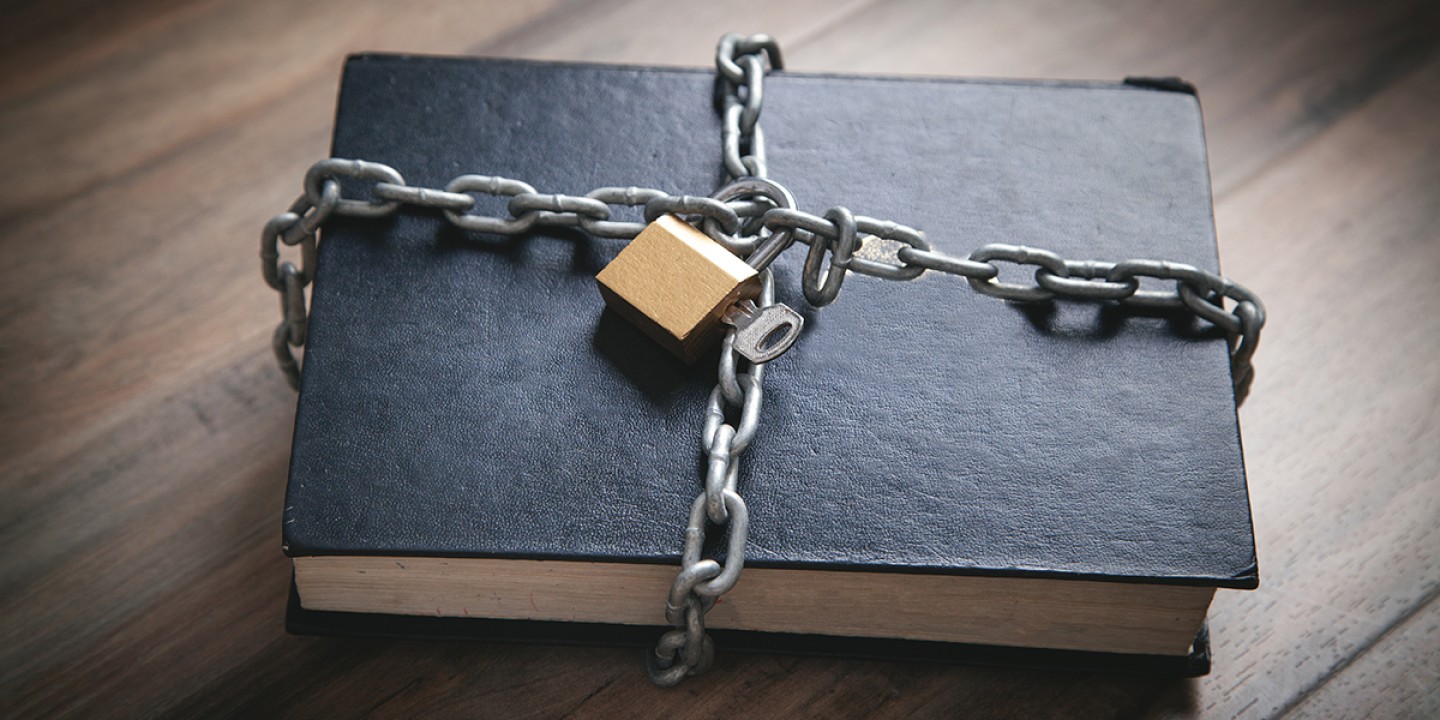

Why books get banned

People fear the impact of difficult books. They aren’t entirely wrong.

Campaigns to remove books from schools and libraries in the United States have increased dramatically in recent years. This book-banning frenzy has risen to such absurd heights that a recent headline read: “Florida rejects 41% of new math textbooks, citing critical race theory among its reasons.”

What’s behind this trend? Some progressive groups have lobbied to ban books that contain racial slurs, such as To Kill a Mockingbird and Mildred Taylor’s Roll of Thunder, Hear My Cry. But most book-banning efforts are instigated by conservatives. Fueled by the rhetoric of elected officials, parents turn to national groups which encourage them to run for school and library boards with the intent to ban books they consider dangerous—from Art Spiegelman’s Maus and Toni Morrison’s Beloved to picture books that celebrate racial diversity or acknowledge the existence of LGBTQ people.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

These campaigns are aimed not at strengthening public education but at weakening it. They are part of a broader movement fueled by billionaires, including the DeVos and Walton families, who have long sought to undermine traditional public schools—an ideological project and, for the for-profit companies that manage many charter schools, a lucrative one. The campaigns succeed not because Americans want their children’s education to be shaped by oligarchs but because they exploit people’s fear and mistrust. Some parents don’t trust teachers with novels that address our country’s history of racism. Others fear that books about inequality will cause their children psychological anguish or undermine their faith in American institutions.

Such fears aren’t entirely unfounded. Written words hold great power, and books can change readers’ hearts. English professor Farah Jasmine Griffin notes that many books, from the Bible to Uncle Tom’s Cabin to Elie Wiesel’s Night, confront readers “with powerful narratives that not only tell the stories of oppressed people, but also hold the mirror up to humanity, often showing us parts of ourselves we’d rather not see.”

These words call to mind Martin Luther’s understanding of the law, which he regarded as inseparable from the gospel. In its theological use, the law offers a mirror, forcing us to see our sin and turn to God for mercy. In its civic use, it makes society safer by curbing evil, which includes helping reform the institutions that allow evil to flourish. In its moral use, it shows us how to live out our vocation, opening us to the Holy Spirit’s work of sanctification.

Books about difficult topics—when approached with openness and attention to context—can function similarly. They can show us our failures. They can impel us to make our society more just. They can transform us into more empathetic people and more responsible citizens.

And forming democratic citizens is at the heart of public education. Schools are “charged with doing the impossible,” write education experts Jack Schneider and Jennifer Berkshire, “carrying out the work of human improvement in a country riven by racial, economic, and geographic inequity.” When powerful people can orchestrate mass censorship through book-banning campaigns, it doesn’t just erode the First Amendment rights of educators and library patrons. It undermines this important work of formation.