Three reasons gerrymandering is bad for democracy (no matter who does it)

It’s not just about an overall partisan advantage.

After the 2020 census, US states began their once-a-decade process of redrawing congressional districts. Many worried that the inevitable gerrymandering would lead to an unprecedented Republican electoral advantage in the House of Representatives—given the party’s dominance in both the state governments that draw the districts and the courts meant to keep them in check—and that this would add to the power of anti-democracy forces on the right.

That’s not quite how this round of redistricting is turning out. Yes, the GOP has pulled off some aggressive gerrymanders in states it dominates. But so have Democrats elsewhere, and other states have more or less maintained the status quo. It’s not news that gerrymandering is a bipartisan problem. What is surprising is that in the current climate, Democrats are managing to accomplish it as effectively as Republicans. While the GOP continues to enjoy many other structural advantages, the 2020 redistricting process is looking like a wash.

It would be a mistake, however, to conclude that outrage over gerrymandering has therefore been overblown. As so often happens, our partisan glasses can obscure deeper, wholly nonpartisan issues of democracy and political culture.

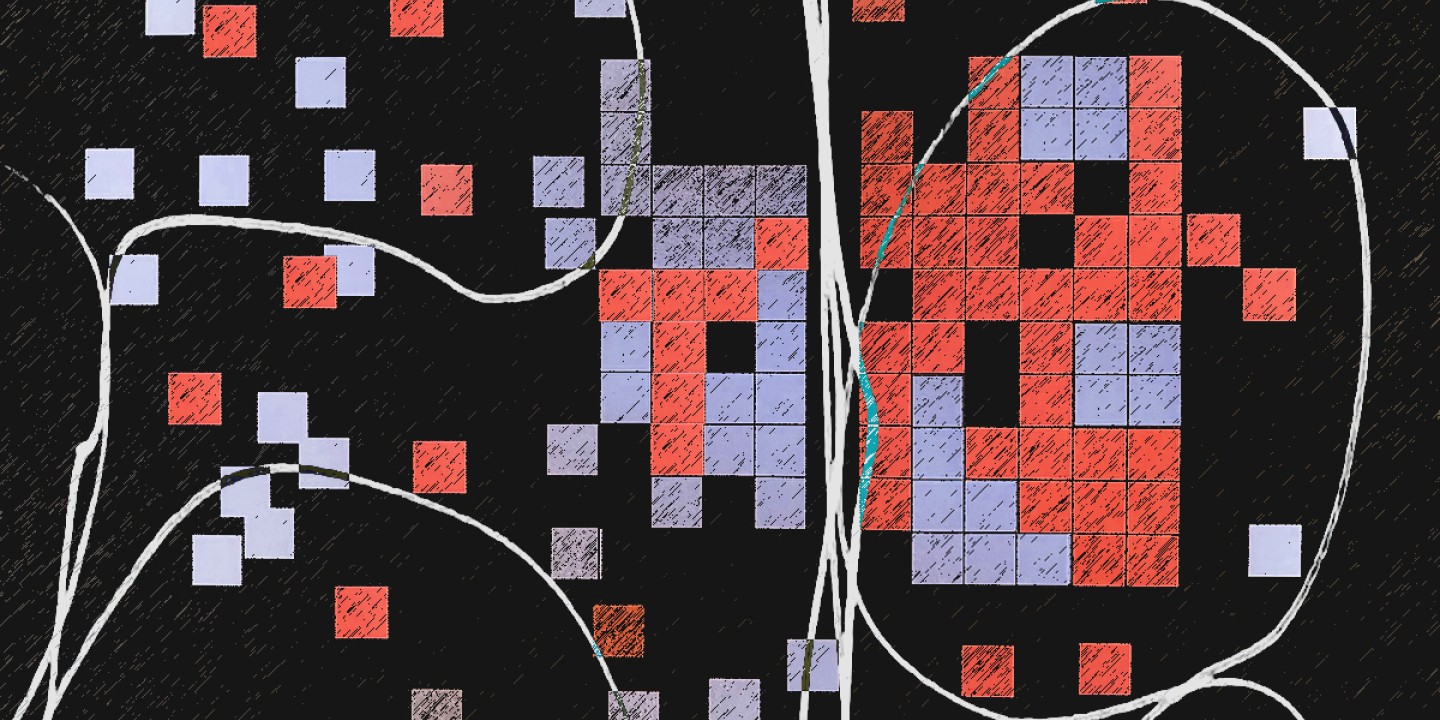

A fundamental problem of gerrymandering is that it makes individual legislative districts less competitive. This is by design: the party in power aims to win most of a state’s districts by a modest but comfortable margin—and to lose the remaining districts by an overwhelming margin. In a perfectly executed gerrymander, one party spreads its votes out to reliably win four or five seats, while the other is left to waste them on one or two landslides. Neither sort of race comes down to the wire.

Noncompetitive districts produce unaccountable legislators. If your seat is safe, you don’t need to listen to your constituents. Even if you face a challenger in a partisan primary, you can ignore voters from other parties.

A lot of voters respond by simply disengaging. Why get involved in the process if your legislator doesn’t seem to value your support or your views? Gerrymandering contributes to the larger American problem of citizens who lack much investment in their own governance, even as their national party affiliation plays an outsized role in their cultural identity.

It also contributes to the growing inability of local geography to bind people together half as well as partisanship does. A legislative district can help shore up a place’s shared identity—but only if the district can be meaningfully identified as a place. The convoluted lines of a gerrymandered map undermine this.

The best available solution to gerrymandering is for states to assign redistricting to nonpartisan commissions, not elected legislators. The nonpartisan part of this has proved easier said than done; we are living, after all, in a time when zero-sum partisanship reaches far beyond professional politicians. Still, if more states would take this route, that would be a significant step toward fairer, more competitive districts.

Our democratic system pivots on legislators accountable to citizens living in particular places. Gerrymandering makes accountability optional, alienates citizens, and subverts the very idea of place. The practice does great harm to democracy—whether it’s done by one major party, by the other, or equally by both.

A version of this article appears in the print edition under the title “Redrawn and disengaged.”