I confess that I’ve never understood the British monarchy or its purpose. Its popularity baffles me. I’ve always thought sensible nations got rid of this archaic model of privilege and family-based hierarchy years ago. It remains a mystery to me what members of the royal family do on any given day. I know they smile and wave a lot, carry on a love/hate relationship with the press, and dress up for plenty of pomp (and not much circumstance) at numerous dedicatory events. But there must be more.

Maybe I haven’t tried hard enough to understand the royals. Friends wonder why I haven’t made time to view the Netflix series The Crown. But now that the Duke and Duchess of Sussex live stateside, and evidently feel comfortable airing private opinion, family secrets, and their own assessment of royalty, the British monarchy may become an inescapable part of US news cycles. My learning curve may shorten significantly.

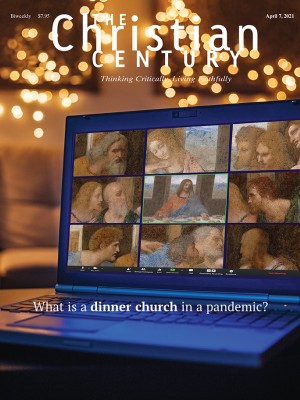

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

Perhaps most puzzling to me is the enthusiasm with which the tax-paying British public funds the royal family. Across all economic classes in the UK, royals are viewed as celebrities—and, as we know, those who adore celebrities often become vulnerable to idealizing their greatness. A lust for celebrity worship feeds a culture of fantasy, the very function of which is to gratify. Since the royals ask nothing of us—remember, their purpose is to gratify—we receive the pleasurable illusion that life is largely effortless, smooth, and without ambiguity. (It’s not clear yet if Oprah’s recent interview with Harry and Meghan will cause a culture of reality to clash more regularly with this culture of fantasy.)

What fans seem to want from the lives of celebrities more than anything else are two things: First, the attractive ride on the coattails of lives that seem more exotic than their own mundane existence. When life feels tedious, there’s a thrill in associating with lives that appear more glamorous and exciting. Second, there lingers in the imagination of celebrity admirers the prospect of an answer to the nagging question of whether they too might also possess some trace of greatness, however small.

The drawback of the first desire is that it fosters secondhand living—life lived through the distorted filter of someone else’s wealth and fame. The drawback to the second craving is that it overlooks our God-given significance and inherent worth.

When the disciples met up with Jesus in a Capernaum kitchen one day, they were reluctant to reveal their chatter about the limelight, their arguing over who carried the most charm. Jesus doesn’t scold them for discussing rank or wanting prestige. He merely presents them with a new flowchart that flips the want for greatness with the must of servanthood. In so doing, he puts the reality of true greatness within everybody’s reach.

“I’m an insomniac-agnostic-egotist,” says Ernest in an old Frank and Ernest comic. “I lie awake nights trying to figure out whether or not I believe that I am as great as I am.” More than a few of us have pondered less egocentric versions of this question, British royals likely included. Jesus has a word for all of us: stop trying to figure out greatness. It’s not a mystery. You have it. Just dissociate it from wealth, power, and fame, and get to work as a servant.

A version of this article appears in the print edition under the title “Searching for greatness.”