The resource we most need during the coronavirus pandemic is human relationship

Looking for signs of hope when social distancing keeps us apart

We typically use the term “natural resources” to refer to things like water, forests, and land deposits containing minerals and fossil fuels. We could make a compelling argument, however, for an even more precious natural resource: human relationships. I am convinced that love and social connection matter more than anything else in life. The priority of such relational wealth may not be obvious, given some of the purchasing and lifestyle decisions we make. But plenty of those decisions turn out to be distractions that only cloud the importance of social needs vital to our survival.

There’s no question that Americans now gather together less frequently in person, meet fewer people overall, and develop less meaningful and durable bonds than previous generations did. Several years ago, while mapping trends of individual isolation, the Barna Group found that one in five adults reported feeling lonely regularly or often. Such a dramatic rise in loneliness has occurred in a relatively short period of recent history.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

Curiously, it’s often a crisis—whether at the family, community, or national level—that strengthens our relational wealth by drawing us closer together. In the aftermath of 9/11, people didn’t want to be alone or apart from loved ones. They wanted to be together. In those anxious days, all kinds of bonds tightened within families and among friends as people stayed close to one another.

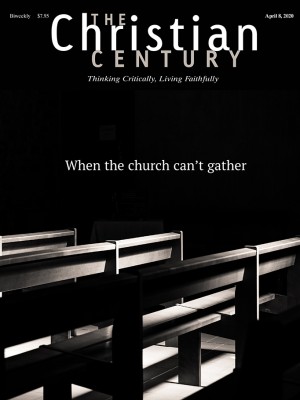

What makes the coronavirus pandemic such a different situation sociologically is that we’re actually being asked to push away from one another. Social distancing requirements physically separate people, just as quarantine measures isolate them. Both deliver stress to the very social connections we depend on. The resulting loneliness, fear, and uncertainty cause many people to poke around for signs of hope.

One individual whose life witness comes to mind as inspirational hope in a crisis is Martin Rinkart (1586–1649). Rinkart was a gifted musician at several prominent churches in Saxony, Germany, before turning to the pastorate. He then served as pastor to the people of Eilenburg for 30 years before his death—years that almost exactly overlapped with the dreadful Thirty Years’ War.

Because it was a walled city, refugees from the surrounding countryside, besieged by invasions of the Swedish military, poured into Eilenburg. It didn’t take long for famine and pestilence to set in. In 1637 alone, 8,000 people died of disease—including other clergy, most of the town council, and Rinkart’s own wife. Rinkart was left to minister to the entire city, sometimes preaching at burial services for as many as 200 dead in one week. Known as a faithful and caring pastor, he gave away everything he owned except for the barest essentials to care for his family.

In the depths of the communal suffering that surrounded him, Rinkart wrote a hymn text with words now familiar to many of us: “Now thank we all our God, / With heart and hands and voices; / Who wondrous things has done, / In whom this world rejoices.” In another verse, Rinkart speaks of a bounteous God staying near us through our anxiety: “Keep us all in grace, / And guide us when perplexed, / And free us from all harm, / In this world and the next.”

It’s a hymn worth coming back to when COVID-19 fears force us to hole up at home and wonder when we’ll see our most precious natural resource fully restored.

A version of this article appears in the print edition under the title “The resource of relationship.”