There’s plenty of discouragement to go around when we think about how often our political and economic systems fail to deliver public goods and services. We’ve grown accustomed to watching legislation that could readily help tackle society’s more intractable inequalities just languish and die. The gap between rich and poor widens with each year. Persistent racial segregation, inadequate housing, discriminatory practices in real estate, unaffordable child care, disparities in health care and education, and environmental hazards in low-income communities are just a few of the ugly problems that cripple efforts to build a more equitable society.

Many of us look for small signs of hope that might circumvent national politics and render relief to people on the margins. Happily, in this regard, the New York Public Library recently made a beautiful announcement. The library will no longer charge late fees on overdue books and media resources, and it will waive all fines accrued from the past. While this may sound like minor tinkering with a tiny piece of everyday life, its impact is huge.

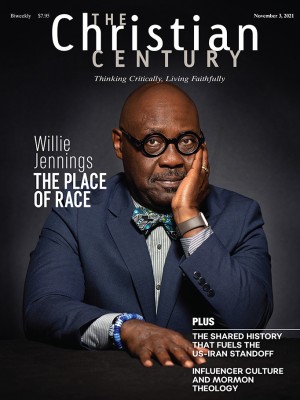

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

NYPL is the largest library system in the country and the fourth largest in the world. It consists of 53 million items spread over 92 separate locations in Manhattan, the Bronx, and Staten Island. (Margaret Kearney wrote about the nearby Brooklyn Public Library in our last issue.) In fiscal year 2019, the library collected more than $3.2 million in late fees. Before its recent decision, more than 400,000 New Yorkers were blocked from accessing books because they owed more than $15 in late fees. The vast majority of those unable to check out a book resided in poor neighborhoods, which meant that those with the least ability to afford fines—low-income New Yorkers, many of them children—had no access to basic tools for learning.

Libraries are “crucial to our democracy of informed citizens,” NYPL president Tony Marx wrote recently. In addition to the full library collection, patrons can find Wi-Fi access, citizenship classes, literacy programs, children’s reading sessions, and English language tutoring. A public library is one of the most democratic institutions we have in the United States. The idea behind a public library is that no one, regardless of background or circumstance, should have to face an access barrier when it comes to reading. “This [elimination of fines] is a step towards a more equitable society,” Marx said. “We are proud to make it happen.”

It’s a gracious institutional move on the part of an enormous library reaching out into a sometimes ungracious world. To suddenly erase fees while trusting patrons to bring books back sounds an awful lot like the arithmetic of grace. The oddity and wonder of that five-letter word is that it’s undeserved, unexpected, and often astonishing. Grace has a way of dispensing with things we’ve been taught: Pay your dues, or else. There’s a fee for that. Don’t expect a freebie.

Lew Smedes, a mentor of mine, was fond of saying that “grace happens when it finally dawns on you that, in Christ, your past isn’t going to catch up to you.” Grace was never meant to be an exclusively religious word, devoid of all meaning in the wider culture.

So perhaps NYPL should adopt this as a new tagline, minus the words in Christ, to underscore its lovely new policy.

A version of this article appears in the print edition under the title “Public grace.”