If we truly took the Bible seriously, I’m not sure we would ever get past the first chapter.

Consider: in ancient Near Eastern societies, it was the king who was thought of as an image of God; it was he who was appointed to rule over others and to mediate God’s blessings for them. This meant that from the very creation of the world, some people were destined to rule over others.

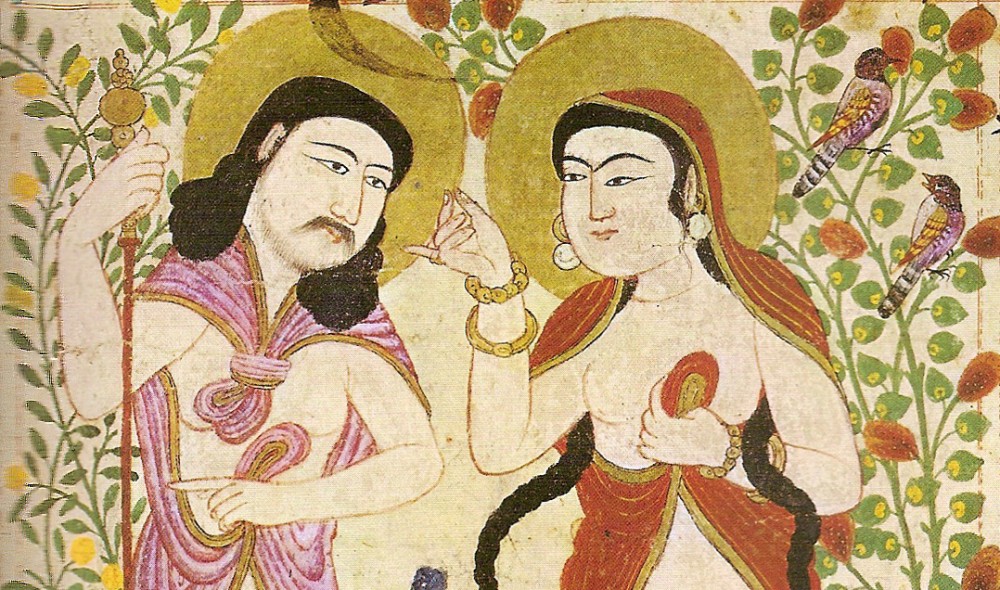

Genesis 1 will have none of this. It is not the king who is the image of God but each and every human being, male and female (Gen. 1:26–28). To put the point starkly, the dramatic claim of Genesis 1 is that we are all kings and queens. No one is destined to rule over anyone else; no one is born with the right to control or dominate others.