The Frontier Interns reenvisioned missions for a postcolonial era

In 1961, Margaret Flory started a new kind of mission program.

When Margaret Flory went to Japan as a Presbyterian missionary in 1948, the reigning model of missions was beginning to come into question. It was too paternalistic and controlling, some veteran missionaries told her. Strong, capable, local Christian leaders were being prevented by Western missionaries from running their own churches. Within a few years, as postcolonial movements gained momentum, the notion of there being “sending” countries and “receiving” ones, and “older” and “younger” churches, was increasingly suspect among missions leaders.

But what, exactly, should the new model of mission be? Throughout the 1950s, mainline Protestant churches and ecumenical organizations struggled with that question.

In 1951 Flory was appointed director of the Office of Student World Relations for the United Presbyterian Church—an office and position she had urged the church’s Board of Missions to create. One of the students Flory worked with was Marian McCaa Thomas. Thomas already knew enough about other cultures to be offended by the idea that American Christians were going to enlighten the world. She wanted to get involved in the church’s international work, but as she recalled recently, she was also interested “in changing the patterns of mission.”

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

In December 1959, Thomas was one of the 3,500 students from 92 countries who attended the 18th Quadrennial Student Conference on Christian World Mission held in Athens, Ohio—a gathering chaired by Margaret Flory. It focused on what it designated as nine nongeographic “frontiers” for witness and service—technological upheaval; racial tensions; new nationalism; militant non-Christian faiths; modern secularism; responsibility for statesmanship; the university world; displaced, rejected, and uprooted peoples; and communism. Martin Luther King Jr. and Nigerian independence activist Bola Ige were among the featured speakers. One attendee, Dwain Epps, then a senior at Oregon State, later to become a top leader at the World Council of Churches, recalls that one evening students from Ghana led a celebration of Ghanaian independence. Liberation theology had not yet been articulated, but the content of its message was in the air.

Flory left the conference with an idea for harnessing students’ enthusiasm for a new kind of mission work. Her plan was to start an interdenominational, international, and interracial program to be called Frontier Internship in Mission (FIM). It would place new college or seminary graduates on one of the nine frontiers of mission, working for two years, usually with and for a local church or a chapter of the Student Christian Movement. Flory’s hope was that these interns would return to the United States full of ideas that would help inspire a new direction for mission. Within a few months she won approval for the program from the International Missionary Council and the World Student Christian Federation. The United Presbyterian Church put up the funds to launch it in 1961. Other mainline Protestant denominations pitched in later.

The FIM program envisioned mission workers living in the same neighborhoods and at the same economic level as their fellow workers, no matter how bare bones. Unlike the situation of many missionaries, who had Western lifestyles, sometimes on mission compounds, FIM interns would learn the local language and share the local life. Study, both before and during the internship, and regular reflection and reporting about their work to the FIM community were also deemed crucial to the program.

What seemed most experimental and exciting about FIM back when the program was designed was the idea that the frontiers were not geographic and were not limited by traditional ideas of evangelization. Frontier Interns could participate in all the ways God was working in the world.

The frontier idea sometimes fell flat, however. For one thing, the English word frontier did not translate well into other languages. (For instance, the French word frontière means “border” or “barrier.”) Second, the frontier idea was quite abstract, whereas the projects proposed by Christians in other countries were very concrete and related to specific local needs. Nevertheless, the FIM program truly was new in that it positioned Christians in other countries to be the ones who called the shots, defining the internships and supervising the interns.

Flory knew that these internships would be challenging. In memos soliciting support from ecumenical officials, she used the phrase “mature and creative” to describe the applicants she sought. She knew finding committed hosts was crucial, too. In each case, she used her many friends in the World Student Christian Federation, in chaplaincies, and in the global ecumenical network to identify and recommend candidates.

Between 1961 and 1974, when the program moved its base to Geneva and was fully internationalized, about 160 young people served as FIs, 140 of them Americans. Although almost all were white, they grew up and were churched and educated in an astonishing variety of situations. As FIs, they served in 48 different countries and on every continent except Antarctica. Each internship was designed to meet local needs and was adapted over time in light of the changing geopolitical context.

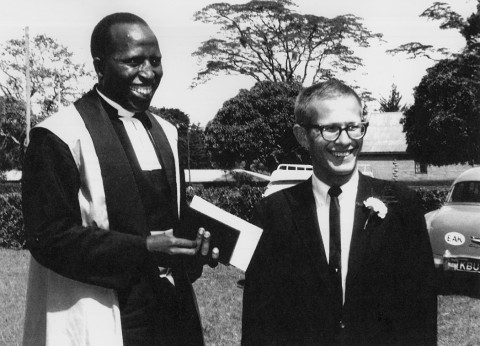

A flavor of FIM can be gained by considering the role of John Gatu (1925–2017), a dynamic pastor in Kenya, a major figure in missions history, and a mentor to three FIM interns. Gatu studied at Princeton Theological Seminary and moved easily in global ecumenical circles, which is no doubt where he learned about Flory and the FIM program. In 1963, when Kenya became independent of the British and Kenyan Presbyterian churches became independent of the Scottish Presbyterians, Gatu was named the first African general secretary of the Presbyterian Church in East Africa (PCEA).

FIM interns Anna and Jerry Bedford arrived in Kenya to work with Gatu, and they got to witness this epic moment of transition. “We saw the British flag come down,” Anna recalled, “and the bubbling up of energy within the church of PCEA was significant.” They were among the first white young people to work directly under Gatu. He and the people of the PCEA welcomed the interns. In their eyes, Americans had thrown off the shackles of British colonialism just as the Kenyans were now doing.

Anna had been born in China, the child of Welsh missionaries, and attended Wheaton College in Illinois, where she met Jerry, who grew up on a farm near Bay City, Michigan. After their marriage, they both attended Union Theological Seminary in New York. They decided to participate in the FIM program in part so that Jerry could better understand Anna’s experience growing up as a missionary kid.

Tom Haller, the third FI who worked for Gatu, arrived in Kenya one year later, in September 1964. In his freshman year at UCLA, Haller had seen a poster headlined “Consider Being a Missionary” accompanied by a drawing of a farmer. That gave him the idea of combining his interest in agriculture with mission work. After graduate study in agriculture, he headed to Princeton for seminary. He thought being a FI would give him a chance to test out his idea of a dual vocation.

In Kenya, John Gatu asked Anna and Jerry to create a youth ministry program. The Scottish Presbyterians had founded a lot of churches but no programs for youth. Anna and Jerry set up a nationwide PCEA youth organization and traveled around the country running weekend youth events. Young people would often walk up to 15 miles to attend these events, which included singing, Bible study, and exercises in role playing that helped students build skills and confidence in interacting with elders.

“The young people then began to start Sunday schools in their churches, because that was something that the elders would allow them to do,” explained Anna. “It gave them some authority and, in a way, it also gave them a way to participate in nation building.” Anna and Jerry developed resources rooted in the local context for these students to use.

After some false starts, Tom Haller launched a vocational program in agriculture that is still going today. The new government took over the farms left behind by the departing British and turned them into cooperatives. Kenyans who had been denied secondary education under colonial rule needed skills and work. Haller trained people to visit these co-ops and analyze agricultural problems, thereby also learning skills they could put to use on their own farms.

Haller and the Bedfords were eventually joined by Joanne Tucker, a California woman who had been dating Haller before he left for Kenya. He encouraged her to join him in Kenya and lined up a teaching job for her at Thogoto Teachers Training College. With some financial help from members of his church, she flew to Kenya after Christmas 1964.

Recalling this moment years later, Joanne wondered aloud, “Did we really do this behind Margaret’s back? I guess we did!” Haller and Tucker were married in the chapel of the college, with Gatu officiating.

John Gatu later became well known in missionary circles for his 1971 call for a “missionary moratorium.” He urged Western churches to withdraw all missionary personnel and funding for a five-year period. His goal was to end African churches’ dependency on foreign support. This effort provoked a firestorm of protest not only in American churches but among African clergy who wanted the flow of funds to continue. Nevertheless, in 1974 the All Africa Council of Churches affirmed Gatu’s stance.

About that time, Gatu sent a Kenyan pastor to New York to serve as a missionary there—an unprecedented move at the time. Flory helped make the arrangements for the Hudson River Presbytery to serve as host. The idea of “reverse mission” was unsettling to many. But that move, Flory later wrote, acted as “a laboratory in the internationalization of mission” and led to the creation of the Mission to the U.S.A. program that brought several hundred missionaries to the United States.

In retrospect, Gatu’s proposed moratorium on Western missions was more a reflection of postcolonial developments in the church than a cause. The number of paid long-term mainline Protestant missionaries had started declining well before 1971. In 1963, the World Council of Churches had already decided that mission needed to be “from everywhere to everywhere,” not from “the West to the rest.” In time, the PCEA became largely self-supporting. By the time of his death last year, Gatu was a much-admired elder statesman.

So what did the churches get for their fairly modest investment in the FIM program? They did not get the reinvigoration of missions that Margaret Flory had envisioned in 1951. The decline of interest in and support for mission in mainline Protestant churches continued unabated. By the time the last FIs returned to the United States in the mid-1970s, the Presbyterian office that organized church visits for returning missionaries—visits that Flory had expected would stimulate important dialogue about mission in the churches—no longer even existed.

But perhaps the effect of FIM lies elsewhere, as historian David Hollinger has suggested in his recent book Protestants Abroad: How Missionaries Tried to Change the World but Changed America. Perhaps the impact of FIM should be evaluated in light of its impact on the “mature and creative” individuals who participated in the program, and in light of how they changed the world.

In surveying FIs, I found three dominant themes. First, they were people who focused on building relationships and bridging cultural differences. Second, they recognized that the American way of doing things is not necessarily the best way. And third, they were strong proponents of grassroots action. The highly individual nature of the internships meant that these ideas were expressed differently in different contexts. Nevertheless, the career trajectories of the Bedfords and Hallers offer evidence of their significance.

Jerry and Anna Bedford brought home a toolbox full of intercultural skills, and one particularly searing memory. When they were staying in Nairobi, the capital of Kenya, they saw children lined up for hours with cups in hand, waiting to receive powdered milk sent from America. With Jerry’s farm and business background, he believed deeply that such a situation should never happen. Parents should be able to provide for their children. He knew that Kenyans could feed themselves if given the resources. That they did not have the resources to do so was just not right.

When he returned to New York, Jerry Bedford came across a posting on a bulletin board at Union Theological Seminary announcing that the Heifer project was seeking a director of development. Then, as now, Heifer donates livestock to people throughout the world to help sustain their families. It was an early program in sustainable development. In 1965, it was quite small and in desperate need of a fundraiser.

The job was a perfect fit. Over the next 35 years, until they retired in 2000, Jerry and Anna helped Heifer grow by developing innovative fundraising techniques, like its Christmas gift catalogue (Anna drew the pictures in the first catalogues with a stylus). Heifer offers people the opportunity to donate an animal in someone else’s name. The Bedfords promoted Heifer “fairs” hosted by Sunday schools or vacation Bible schools, which told children about how families would be helped by receiving animals. In designing Heifer’s promotional materials, Anna and Jerry rejected the use of photos of starving children that were meant to open wallets by evoking pity. Instead, they promoted the dignity of every human person and stressed that the people being helped were members of God’s one family.

In Arkansas, where they lived, Anna and Jerry also helped organize churches, farmers, and government hunger agencies to start a food bank, Arkansas Rice Depot, now regarded as one of the best in the nation. Hunger, they insist, trumps theology every time. “It wasn’t sustainable development,” said Anna of the food bank, “but children can’t wait.”

Tom Haller learned a sobering lesson in Kenya, too. He saw that the rational-technical approach to agriculture that he learned in American universities had real limitations. “I always saw things in boxes,” he said, “but they [the Kenyans] saw things connected and in layers and interacting. And politics was in everything.” The Kenyans offered him “a much richer view of the world.”

After getting a Ph.D. in agricultural economics and serving as an agricultural adviser in Colombia and Peru, Tom and Joanne moved to Davis, California, so that she could attend graduate school. When he learned that small farms in the area were in imminent danger of being wiped out by industrial agriculture, he decided that small farmers needed an organization of their own.

Tom created the Community Alliance with Family Farmers. For its first 15 years, CAFF focused on opposing policy changes that would force small farmers out of business and on supporting organic farming and direct distribution food systems. Its campaigns were memorable. On one occasion, to oppose a bill being advanced by large dairies to permit use of bovine growth hormone, it stationed three cows on the steps of the capitol bearing signs saying “No Lactation Without Representation” and “Don’t Shoot Me Up.”

Tom was sometimes accused of being a communist, but over the years his ecological understanding of food and farming—an understanding first inspired by his experience in Kenya—and the policies advocated by CAFF gained traction. He is particularly proud of the Peace and Justice Award he got from KPFA, the Pacifica Foundation’s flagship radio station in the Bay Area.

“Peace and justice. That’s how I see my life’s work,” he said. CAFF—now merged with the Farmer’s Guild—continues to advocate for family farmers and sustainable food systems.

The FIs are now in their seventies and eighties. Some had international careers in humanitarian relief, health, human rights, education, journalism, or nongovernmental organizations. Others became scholars and educators, particularly in African studies, Asian studies, or Latin American studies, all newly burgeoning fields at American colleges and universities in the 1970s. Many worked in their local communities to bridge the divides of race, language, and culture. Some pastored churches, often in inner-city neighborhoods, or served as chaplains (though not as many became pastors as was expected in 1961).

The impact of FIM in many cases extends to the lives of entire families. Some FIs never returned to the United States to live permanently. Others have visited places where they served, sometimes more than once, often leading groups. Their adult children often have had international lives. Many FIs have hosted friends they made during their internships in their homes in the United States. The Internet and social media have helped foster reconnections.

“Once a FI, always a FI,” said Mark Schomer, a mission kid and FI who worked with the Kimbanguists in the Congo in the late 1960s and who now, with his wife, runs the family’s coffee plantation in Guatemala and works on economic development in their region. “It’s like when you join the clergy. You don’t just leave it.”

Marian McCaa Thomas headed to South Korea in 1961, right after graduation from Oberlin, to live in a community of reconciliation with a South Korean woman and a Japanese man and work with college students. She said the FIM pattern of study was one she adopted for life: “You are in the situation, you study the situation, you listen, you learn, you ask questions, and then you find out what you can do, in cooperation with the others who are concerned about the same things, to address the problems and relate the Christian faith to those issues.”

About half the FIs I surveyed are now unaffiliated with a church. Perhaps that’s because they became more globally oriented at a time when many churches were becoming more inwardly focused. When they got back to the States, they just didn’t fit in. One FI describes himself as part of a “wandering tribe,” one of those who never were able to find a church community that embodied that Frontier Internship approach to life. Other FIs worked as pastors or lay leaders to create congregations that did embody that ideal.

This result is not the outcome Margaret Flory expected in 1960. But her goals for FIM were clear, and she never wavered from them: she wanted to foster deep relationships throughout the global ecumenical community, helping Christians around the world learn from one another and helping one another change the world. She remained incredibly proud of what FIM had done to advance that vision. And maybe, along the way, she did create a new model of mission.

A version of this article appears in the print edition under the title “The Frontier Interns.” Further information about her research is available through the Boston University School of Theology Center for Global Christianity and Mission.