Recipes for a revolution

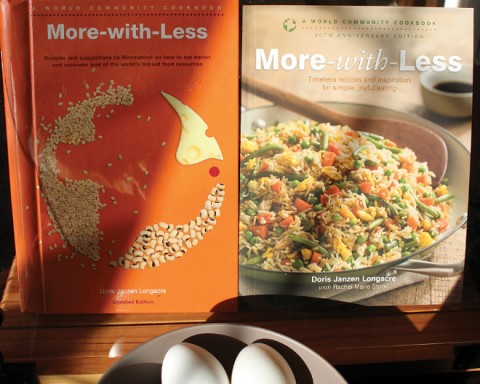

The More-with-Less cookbook called for responsible eating long before it was cool.

I don’t remember the name of the camp counselor who inspired me to be a vegetarian. I remember only that he skipped the camp-issued hamburger in favor of a peanut butter sandwich, and that he was very, very cool.

Even as a teenager, I knew that wanting to be cool wasn’t a very good reason for me to give up meat. So I went in search of others. Animal rights? Sort of, but I’ve never been much of an animal lover. Health? Many of my meatless meals consisted of French fries and cheese. Then, somewhere along the way, I learned that making a hamburger is a pretty inefficient use of land and other resources. Ah-ha, I thought: environmentalism. That was a cause I could rally behind.

Going meatless was the first of what I’ve come to think of as my food revolutions: sometimes subtle, sometimes dramatic shifts in the way I understand my relationship with food. Another revolution came on a youth group trip to Koinonia Farm in Georgia when I tasted fresh-picked tomatoes; another years later when I read Barbara Kingsolver’s Animal, Vegetable, Miracle and began to pay attention to where my food comes from.