What is the Amazon bookstore for?

Amazon sells books at their brick-and-mortar stores, but that's not why they want me to come.

Near the Kindle display at the brick-and-mortar Amazon bookstore in Seattle, I overheard one man say to another, “Some people like the feel of a book.” Then he shrugged and added, “Even though you could put every book in this store on one device.” He chuckled.

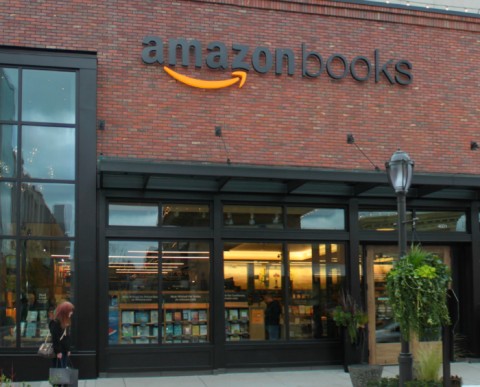

Amazon opened its Seattle bookstore in 2015 and opened another in San Diego this past summer. It plans to create as many as 400 such stores in the coming years.

Yes, you can buy books there. The small Seattle store, set in an outdoor mall alongside a Banana Republic, a Sunglass Hut, and a place called Seattle Sun Tan, carries books in fiction, nonfiction, travel, and cooking and has a substantial section of children’s books. It looks more or less like every other soulless chain bookstore.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

On the surface, the decision by the Internet retail giant to open bookstores affirms the continuing place of physical books in the digital age. Sales of print books have been growing while sales of e-books and digital reading devices are stagnating. From the depths of the 2008 recession until 2014, the number of bookstores belonging to the American Booksellers Association has grown 20 percent. Bookstore sales have been up every month this year and were up overall in 2015. People’s love for the book appears to be unflagging. By opening actual bookstores, Amazon—widely blamed for putting bookstores out of business—seems ready, as one industry analyst puts it, to “reap the rewards of what they helped destroy.”

But Amazon does not want just to participate in the rebounding popularity of bookstores; it also wants to transform what a bookstore does. Specifically, it wants to merge the old world of the bookstore with the new world of digital devices.

The heart of the Amazon bookstore is given over to devices, especially Kindle and Amazon Fire, Amazon’s television service, akin to Apple TV. Customers at the store have a chance to experiment with these devices, and they are encouraged to download the Amazon app in order to “get more information about the books” and to quickly pay for them.

In an experimental mood, I installed the app and tried to use it. But I kept getting an “oops” message, and later I uninstalled it. Meanwhile, a child twice set off the Kindles’ in-store alarms, sending a thin siren sound through the room.

As employees had to keep explaining to customers, the prices printed on the books were not the actual prices. To find the actual price, you had to carry the book to the end of the aisle and run it under a scanner—or else use the Amazon app, which would have been more convenient if it had worked properly. The added benefit to Amazon of people using the Amazon app would be learning which books customers are scanning and thereby gleaning more information on what to advertise to us the next time we turn on our computers.

I scanned the book chosen for my book club’s next meeting: The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao, by Junot Díaz. The list price was $21.00 but the Amazon price was $9.62. I then used my phone to go online to amazon.com where I learned that I could buy a used copy for $1.62. I was hard-pressed to find a motivation to buy it in the store.

Amazon also uses its website sales data to decide what books to stock in the store and what books to put on display. A sign on the “new and recent fiction” table said that the books had been chosen by “customer ratings, preorders, sales, and popularity on Goodreads—plus books we love.” Nothing about that method of recommending books inspired me, and I was as unmoved by my fellow readers’ five-star ratings in the store as I am online.

The child who had set off the Kindle alarm was now playing with the remote control for a video game called Hovercraft Takedown on Amazon Fire.

If Amazon has a heart—which I suspect a large number of authors and publishers would dispute—it isn’t in its bookstores. Its bookstores are designed primarily as opportunities to explore the interplay between technology and physical retail.

Some industry analysts wonder if Amazon has opened its bookstores in order to improve its delivery and returns processes, which can be handled on site. Writes Computerworld: “Retail stores could double as product pickup locations, distribution warehouses and, eventually, drone airports from which products are flown to nearby homes and businesses.”

The store serves as an enticement to what the technology industry calls “gateway” products. If you buy a Kindle at Amazon, you might also use Amazon to download movies and music.

The store also introduces Amazon’s new product, Echo, a voice-activated device that allows people to buy items just by speaking. The technology is so new that customers probably need an opportunity to try it out. What better place to try it out than an experimental bookstore? One analyst explained the stakes: “When Barnes & Noble sells a book, it sells a book. When Amazon sells an Echo, it sells a lifetime of easy ordering of everything from Amazon.”

Though I will probably not return to an Amazon bookstore, I was fascinated to see how Amazon continues to work at transforming our buying habits.

A version of this article appears in the October 12 print edition under the title “Real books, fake store.”