Unremembered

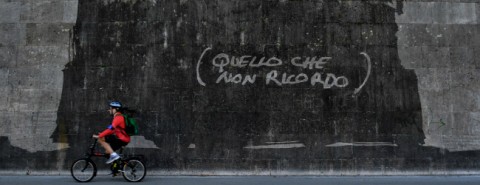

In Rome this spring, a new work of art appeared on the embankment wall of the Tiber River. Containing some 80 images, many of them more than 30 feet tall, South African artist William Kentridge’s nonchronological frieze of Roman history stretches for a third of a mile. It’s an organic work of art, with images made from the patina of grime that has accumulated on the wall over the years. Using a technique called “reverse graffiti,” workers placed enormous stencils on the wall and pressure-washed around them. When the stencils were removed, the images remained.

The frieze depicts a procession of images familiar from Roman art, history, and tradition: the Winged Victory of Samothrace recording Rome’s military exploits on a shield; the wolf who nursed Rome’s founders, Romulus and Remus; Marcus Aurelius on horseback; the angel atop Castel Sant’Angelo, sheathing his sword. Kentridge titled the frieze Triumphs and Laments, drawing attention to triumph’s costs, the terrible intimacy of glory and loss, victory and despair. Many of the images recall violent displacements: soldiers returning to Rome after the sack of Jerusalem, or refugees with their possessions strapped to their backs boarding a boat for the dangerous crossing to the Italian island of Lampedusa.

Other images reveal a sly humor: a nun receiving communion from a moka, the iconic Italian coffeepot; Marcello Mastroianni and Anita Ekberg standing together in a bathtub—a reference to their meeting at the Trevi Fountain in La Dolce Vita. But everywhere the weight of history is evident. As the Winged Victory inscribes the story of military conquest on her shield, she falls and begins to shatter. Gaunt, skeletal animals stalk through the procession, haunting it with a vision of the losses and laments each triumph bears in its wake. And occasionally the movement of the procession is interrupted by a body lying motionless on the ground: Remus, killed by his brother on the day Rome was founded; filmmaker Pier Paolo Pasolini lying murdered on the beach; Giorgiana Masi, a student shot to death in a demonstration in 1977.