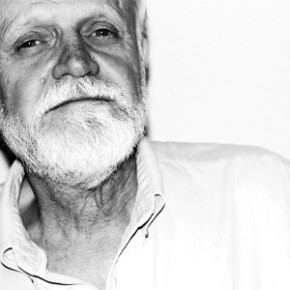

Faith on the edge: Writer Dennis Covington

"Belief is not the 'substance of things hoped for.' Faith is."

Dennis Covington’s 1995 book Salvation on Sand Mountain: Snake Handling and Redemption in Southern Appalachia was a National Book Award finalist. He went to El Salvador as a freelance writer in the 1980s and has taught writing at Texas Tech and the University of Alabama at Birmingham. His latest book, Revelation: A Search for Faith in a Violent Religious World, recounts his travels in Turkey, Syria, and Juarez, Mexico. During one of his last trips to Syria he suffered a nearly fatal brain injury from an explosion near the Great Mosque of Aleppo.

What was your life like before you started writing about snake-handling Christians?

Because of experiences I had in El Salvador during that country’s civil war, especially meeting children who had undergone terrible trauma, my wife and I stopped drinking. Our lives had been really messy, and we were miserable people before, but as a result of my awakening in Central America we started going to church again. And then our first child came along. It was a gift. We were firmly engaged with our church, which was a large urban progressive Southern Baptist church. We did service at the church and took care of the nursery. I drove the church bus for people at the halfway houses; we were members of the AIDS care team. We prayed at night and took turns reading the Bible to each other. So even before the snake handling our household was occupied by the Holy Spirit.