Fluent in God’s work

A few weeks after moving to Rome, my daughter returned from dinner with classmates and announced that sharing a meal with people from around the world and trying to communicate in each other’s languages was life’s greatest pleasure. “I want my life to be full of meals like these,” she said.

I’m learning a lot from watching my daughter navigate in multiple languages this year. “Ah, the young,” a shopkeeper told me as he witnessed how much more at ease my daughter is in Italian than I am. “Their brains are so fresh!”

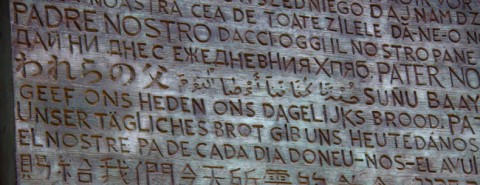

I recently signed up for an Italian class to try to catch up with her, and it’s clear that a fresh brain would be a definite advantage. But there are other qualities needed. Most necessary is a blend of humility and fearlessness, a willingness to risk embarrassment and failure over and over again. The star students of language classrooms are the ones most comfortable making mistakes and most eager to be corrected. They are also having the most fun. One of my classmates, a young priest from the Republic of the Congo who is learning his fifth language, advised me to listen to more Italian music and watch more Italian films. “You have to find pleasure in a language,” he told me, “in order for the logic of the language to reveal itself.”