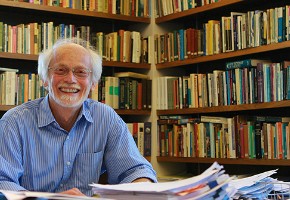

Books that transform: Eerdmans editor Jon Pott

Earlier this year, Jon Pott stepped down as editor in chief at Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Company after a career of almost 50 years. During that time he oversaw tremendous growth at Eerdmans and witnessed dramatic changes in religious publishing.

Eerdmans is somewhat hard to describe: it has a Dutch Reformed background and is socially progressive and theologically rather conservative. It is intellectually rigorous but interested in a nonacademic audience. How would you describe it?

I see myself as very much in line with the thinking of Bill Eerdmans and other predecessors. During my time as editor, Eerdmans benefited from and was able to nurture an emerging center ground between progressive evangelicals on the one hand and traditional mainliners on the other.