The future is Filipino

When Pope Francis visits the Philippines in January, we will undoubtedly hear a great deal about that country’s importance on the global religious scene. Partly that’s a matter of raw numbers. Already one of the world’s three largest Catholic nations, it may by some measures lead the pack within a quarter century or so. By 2050, there could be 100 million Catholic Filipinos.

The church also has a charismatic leader in Luis Antonio Tagle, archbishop of Manila. Only 57, he features prominently in speculation about the next papal election, whenever that might occur. If Tagle is not chosen, it is likely that some Filipino will become the first nonwhite pope since the early Middle Ages.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

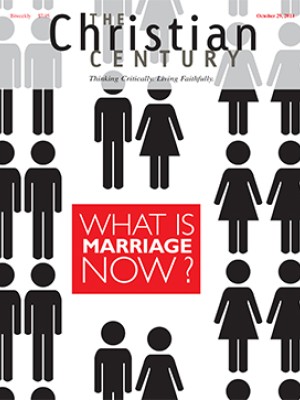

John Allen, the superbly informed expert on all things Catholic, rightly stresses the central role of the Philippines in the Catholic future. He also warns that the Philippine experience belies any Western hopes that culture wars and church-state conflicts might fade in consequence of rapid social change. The Philippine church is powerful and politically influential, priding itself on its heroic role against the Marcos dictatorship of the 1980s. In recent years, the Philippine hierarchy has been consistently at war with the national government over official attempts to expand access to contraception and over sex education in the schools. Threats of excommunication have been flying. Contraception is still a primary battlefield of cultural politics; same-sex marriage is barely even discussed.

In numerical terms, the Philippine church seems set for future growth, especially when set against other major Catholic nations. Unlike Catholics in Brazil or Mexico, Filipino Catholics have faced little serious competition from either insurgent Pentecostal denominations or secularization. While the country is a haven of very traditional Catholic faith, the church ably accommodates believers who might be tempted to defect to Pentecostal movements. It successfully channels dissent into its very powerful lay orders, which offer members a vibrant charismatic experience within a Catholic framework. To use corporate language, the Philippine hierarchy has done a superb job of customer retention.

On the basis of recent history, then, it’s not too wild a leap to suggest that the Catholic future is Filipino.

But that projection comes with a couple of caveats. Some issues now only on the horizon may well become significant. One of these distant shadows is demography. Over the past century, the Philippine population has swollen from perhaps 9 million in 1914 to 100 million today, and that number is projected to grow to 150 million by 2050. Mainly, that growth is due to high fertility rates. In 1960, the average Filipina woman could expect to have seven children during the course of her life, and as recently as 1983 the rate was still 5.1, giving the country a classic Third World population profile.

Since the 1980s, though, the fertility rate has plummeted. It is 3.1 today—still high by global standards, but most projections suggest a continuing decline, which will soon fall below the replacement figure of 2.1. Demographically, the country is moving toward European conditions, although with a lag of several decades behind Spain or Italy.

Most observers would see fertility decline as a good thing, resulting as it does from a growing emancipation of women, who participate more fully in the paid workforce. Yet a collapse in fertility rates correlates neatly with secularization. The more people separate marriage and sexuality from the obligation to beget and raise children, the further removed they become from church teachings. The Philippines is still not close to European secularism, but developments over the next decade or so will bear watching.

The Philippine church is also starting to face criticisms of a kind very familiar in the West, albeit on a limited scale. Although child abuse scandals have been limited, Cardinal Tagle has asked astutely whether cultural constraints might have made victims reluctant to report abuse. He has publicly warned fellow bishops that they should take preemptive action rather than waiting for “a bomb to explode.” As Ireland has shown in recent years, such a bomb can quickly bring antichurch criticisms into daylight.

We might see auguries of approaching trouble in the scandalous success last year of Aries Rufo’s sweeping exposé Altar of Secrets: Sex, Politics, and Money in the Philippine Catholic Church. (Most of the sexual content of the book involves adult heterosexual relationships, rather than child molestation.) Little in the book is terribly surprising, but what is remarkable is that so much dirty ecclesiastical laundry is now being washed publicly, and that consumers are buying the book.

The Philippine church seems to be in robust health, but Cardinal Tagle is wise not to take that for granted.