Church against state? Resident Aliens at 25

A funny thing happened on the way to the church-as-polis: I can now imagine being a resident alien and invested in the state, in all of its glorious failing.

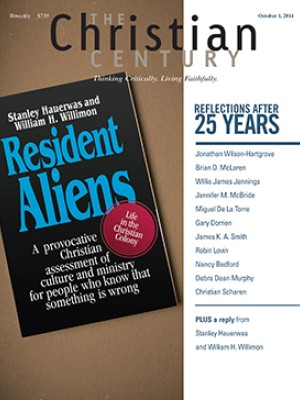

In 1989, Stanley Hauerwas and William H. Willimon sparked a lively debate about church, ministry, and Christian identity with their book Resident Aliens: Life in the Christian Colony. Twenty-five years later, we asked several pastors and theologians to offer their perspective on the book and its impact. (Read all responses.)

Reading Resident Aliens is a kind of Rorschach test: the way a mainline Methodist reads it will be different from the way someone like me—an evangelical (of sorts) in the Reformed tradition—does. An heir of Abraham Kuyper encouraged to “transform culture,” I learned from Hauerwas and Willimon how often, under the banner of cultural transformation, we march ahead into cultural assimilation.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

It wasn’t until I read Resident Aliens that I realized I lacked a functional ecclesiology. Hauerwas and Willimon woke me up to a sense that the church has its own cultural center of gravity. We didn’t have to figure out how to hook up “Christ” with “culture” because the body of Christ is a culture, and specifically a formative culture.

For those of us breaking out of fundamentalism, the Reformed tradition offered a “common grace” license that enabled us to say yes to culture. But in our new enthusiasm for affirmation, we tended to lose the other side of Kuyper’s approach—an emphasis on antithesis. Resident Aliens was apocalyptic for me in the sense of unveiling the deformative power of those other spheres of life we were so eager to affirm and transform.

Many of my generation, I think, received this antithesis as a dichotomy: church instead of state. We would devote ourselves to setting up an “alternative polis,” the liberal democratic state be damned. I don’t think this was the authors’ intention, but their rhetoric didn’t do much to curb that conclusion.

But a funny thing happened on the way to the church-as-polis: rereading Augustine’s City of God, alongside the work of Oliver O’Donovan and Peter Leithart, I can now imagine being a resident alien and invested in the state, in all of its glorious failing. The antithesis is always ad hoc. And the Spirit can bend political orders.

You might say that, ironically, Resident Aliens brought me to a new, highly qualified appreciation of Christendom—not in the sense of a diminished civil religion, but in O’Donovan’s robust sense of a society that bears the crater marks of the gospel’s impact.

Charles Marsh’s account of the civil rights movement in The Beloved Community was a catalyst in this respect. He described a “resident alien” community that hoped its specifically Christian witness would make a dent in the laws of the land. Marsh’s tale also narrates what happened when the civil rights movement lost its ecclesial center of gravity. Faithful witness is a precarious dance.

The citizen of the city of God, Augustine emphasizes, will always find herself thrown into a situation of being a resident alien in some outpost of the earthly city. This demands neither a positive or sanguine stance vis-à-vis the earthly city nor a fundamentally dismissive stance with respect to political society. Rather, the first political impetus is one of calculated ambivalence and cultivated aloofness tempered by ad hoc evaluations about selective collaborations for the common good. It’s not just a question of whether to be resident aliens, but how.