Keeping Christmas

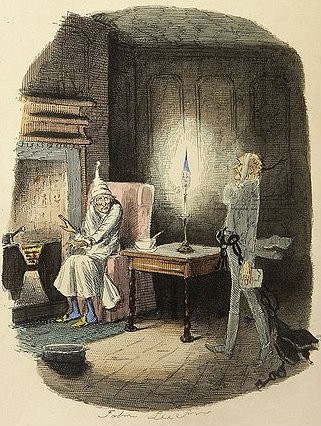

In Charles Dickens’s A Christmas Carol, Ebenezer Scrooge declares war on Christmas: “Out upon Merry Christmas! What’s Christmastime to you but a time for paying bills without money; a time for finding yourself a year older, but not an hour richer. . . . Every idiot who goes about with ‘Merry Christmas’ on his lips should be boiled with his own pudding and buried with a stake of holly through his heart.”

I first saw A Christmas Carol as a child, at an amateur church production. I still recall sitting bolt upright in the pew when I heard Jacob Marley’s ghost moaning and thumping up the stairs with clanging chains and money boxes dragging along behind him. I loved Bob Cratchit and Tiny Tim, of course, and the way the play ended, with Scrooge transformed and redeemed. (Best of all, Santa Claus appeared afterward and gave each child a small cardboard container with a string handle—full of chocolate candy.)

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

Charles Dickens was close to the mark. The gospel is about the power of love to change, redeem and save and to make a difference in the lives of men and women. A generation after Jesus’ death and resurrection, one of his followers wrote, “Beloved, let us love one another, because love is from God. . . . God is love and those who abide in love abide in God, and God abides in them.” What a remarkable notion!

Every civilization and culture has pondered ultimate questions. Early philosophers concluded that if there is an ultimate being, it must be perfect, complete and lacking nothing. Such a god would have no needs and no feelings or emotions. The Greeks called this the apatheia of God, from which we derive the word apathy. God, they insisted, must be untouched and uncontaminated by the messy neediness of humanity.

The gospel proclaims the exact opposite: God does have feelings and is hopelessly and relentlessly in love with the world and human beings. God lives not in textbooks or creeds, not in temples, cathedrals and churches, but in acts of human love.

In Encountering God, Diana Eck says that “the language of faith is the language of affection. . . . Faith language is analogous to the language we use when we say ‘I love you.’”

The miracle of love is that the more you love, the more alive you are. Fortunate people have learned how to love, how to give love, resources, gifts and life itself. At its simplest and best, Christmas is, for the young, the excitement of gifts received; for those older, it is a yearly reminder that it is not only better to give than to receive, but a lot more joyful as well. It’s why we give gifts, send greeting cards and pen long, heartfelt Christmas letters. It’s why we’re kinder and more generous than usual and shower neighbors and friends with cookies and jars of homemade jam. It’s a reminder of what it means to be fully alive and, in a small way, an instrument of God’s life-transforming love.

And it’s never too late. After a harrowing, sleepless night, Scrooge becomes a changed man. He sends the biggest turkey in the neighborhood shop to the Cratchit home. He wishes his startled neighbors and shopkeepers a Merry Christmas. He even goes to church.

On the book’s last page, Dickens writes of Scrooge: “His own heart laughed . . . and it was always said of him, that he knew how to keep Christmas well.”

Keeping Christmas is believing in the transforming power of love. Wendell Berry must have had that power in mind when he wrote: “I know that I have life / only insofar as I have love. / I have no love / except it come from Thee. / Help me, please, to carry / this candle against the wind.”