Christendom in Georgia

Westerners generally know little about the Caucasus region, and much of what they know is highly negative. In recent years, the North Caucasus has produced a litany of horror stories from Chechnya, Dagestan and other neighboring territories where Muslim populations struggle for independence from Russia.

The South Caucasus, however, has a very different history, and Christianity plays a central role. Like its neighbor Armenia, Georgia has ancient Christian roots. Georgia’s history resembles that of many Christian kingdoms that flourished in earlier times but which then lost their independence and sometimes their faith. But Georgia remains overwhelmingly Christian, despite repeated persecutions by Muslims, rival Christian denominations and most recently atheist communism.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

As is typical of small states that have had to struggle constantly for their existence, Georgia’s national and religious identities have always intimately intertwined, and both are sustained by a powerful awareness of past suffering and martyrdom. Parallels with Ireland and Poland spring to mind.

Although a united Georgian kingdom emerged only in the tenth century, several precursor states existed. The most important, confusingly named Iberia, converted to Christianity in the early fourth century. Georgia may well be unique in crediting its conversion to Christianity to the preaching of a woman, Saint Nino, a former slave who earned the title of Equal to the Apostles. (The country’s other incomparable hero is also a woman, its medieval queen Tamar.)

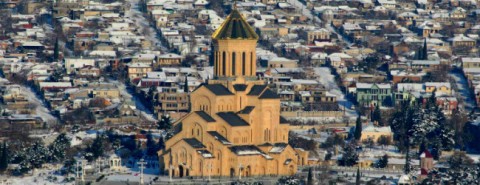

Nino reputedly raised a cross over a pagan temple near the town of Mtskheta, which became the shrine both of Georgian nationhood and faith. Mtskheta is home to the Svetitskhoveli Cathedral, which was the royal mausoleum, and nearby stand the monastery complexes of Gelati and Jvari. Georgia has dozens of medieval monasteries, often situated against the awe-inspiring backdrop of towering Caucasian mountains.

Much of Georgian history revolves around the troubled interaction of Christianity with Islam. The city of Tbilisi was for centuries the seat of an Arab emirate, which in turn fell before a Christian reconquest. Muslim power later reasserted itself.

In 1226, the Persian king captured Tbilisi in one of the most frightening episodes in the nation’s history. The invaders killed many Christians for refusing to renounce their faith and partially dismantled some of the country’s greatest churches. The Georgian church still commemorates what became known, dubiously, as the Hundred Thousand Martyrs of Tbilisi. In 1386, a Georgian king saved his life by accepting Islam.

For several centuries, successive Muslim invasions inflicted enormous damage through massacres and mass deportations. In the 18th century, Christian Russia became the dominant power in the area, but that did not end Georgian suffering. Russia was an Orthodox Christian empire, and it insisted on remolding the Georgian church in its own image, imposing the Slavonic language and eliminating much native artwork. The Georgians had to renew their long struggle for an independent church, for “autocephaly.”

In the 1890s, Tbilisi’s seminary expelled one of its students, a Georgian named Dzhugashvili, who went on to notoriety under his adopted name of Josef Stalin. Georgia soon became a hotbed of communist militancy and armed terrorism. Under the Bolshevik regime, and still more under Stalin himself, the church endured decades of purgatorial sufferings. Monks and priests were slaughtered, and most of the historic buildings were ruined or secularized. During the communist era, over 90 percent of Georgia’s Orthodox churches were closed.

Only since 1990 has Georgia been able to establish its independent identity. In that year, the patriarch of Constantinople finally recognized the church’s autocephalous status, and in 1991 Georgia formally broke with the former Soviet Union. The new country is small, with just 4.5 million people in a territory less than half the size of the American state that shares its name. But it cherishes its Orthodox Christian heritage. Some 84 percent of Georgians declare themselves Christian, and virtually all of those follow the Orthodox Church that has become synonymous with patriotism and traditional morality.

Successive Georgia governments have shown conspicuous support for the church, to the point of cementing a close church-state alliance. The nation’s first president was baptized into the church and made an agreement with the hierarchy to restore religious teaching in schools. The national constitution explicitly recognizes the church’s special position in society. The clearest sign of this intimate alliance is the construction of a brand new cathedral in Tbilisi, Holy Trinity (Sameba), between 1995 and 2004. The new building serves as the seat of the patriarch.

Many Western Christians look askance at such an identification of faith and nationalism. In most cases, though, their own nations have not had to spend more than a millennium defending their mere existence against seemingly irresistible invasions and persecutions, clinging desperately to the hope of divine assistance.