Sunday, July 14, 2013: Luke 10:25-37

When I was in high school I was fascinated with the field of evolutionary psychology. With the help of authors like Robert Wright and Richard Dawkins, I believed that I could see through the veil of what we humans do and what we say about what we do and then discover what was at the heart of our motivation. As it turns out, everything from heroism to heartbreak is the direct result of the battle of our “selfish genes” (Dawkins’s phrase) for survival, supremacy and self-replication.

I wasn’t able to grasp then that much of what passes for evolutionary psychology is rather shoddy science. Yet this “science” has gained in popularity for the good reason that we humans are always inquisitive, especially about ourselves, and for the bad reason that we are drawn to simplistic, comprehensive stories, especially stories that cast suspicion on our experiences and emotions.

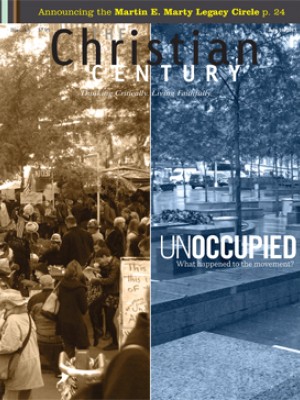

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

I’ve since moved on from my evolutionary psychology phase, but I did learn from it. Even if a comprehensive account of human life is impossible to acquire through study of genetic variation and selection, we’ve gained a great deal of insight on how the history of our species has prepared us to navigate the world.

The evolution of our concept of survival and how this concept affects how we relate to others comes out in Luke 10, when an earnest lawyer referred to the second commandment (Lev. 9:18) and asked Jesus, “[But] who is my neighbor?” The story Jesus told in response sheds light on our instincts toward both our own safety and our neighbor. In our time we seem to take for granted that the word neighbor can include all of humanity, but in Jesus’ day people didn’t think in such abstractions. Instead they might have asked themselves: Is my neighbor a kinsman or kinswoman, a person bound to me by obligation, a member of my tribe? Can even my nation’s rivals and occupiers be neighbors?

Jesus answered the lawyer—and 21st-century Christians—with a story about a man who was attacked and nearly killed by bandits. A priest and a Levite each passed by the man without stopping. But a third man, a Samaritan, was “moved with pity” (a visceral word in Greek) and stopped, bound up the man’s wounds and took him to an inn. Which one of these three men was a neighbor to that bleeding man, Jesus asked?

This story has often been given an unnecessary and anti-Semitic interpretation. We’re told that the priest and the Levite were bound by Jewish purity laws that prevented them from having contact with corpses or human blood, as if their Jewishness forced them to be heartless. But the story is simpler and clearer when we view it from an evolutionary perspective.

Researchers know that scenarios like this one trigger evolutionary instincts for self-preservation and genetic survival. A bleeding, possibly dead man on the road from Jerusalem to Jericho was a clear indication of danger. His attackers might have been close by, or he might have been in league with them, seeking to lure softhearted travelers. The priest and the Levite were not doing anything shocking in passing by, and the Samaritan was going against powerful instincts in stopping to help.

Evolutionary science has found interesting data on our tendency to help members of our own clan or ethnic group. Racism, if that’s the right word, has been discovered even among rhesus monkeys. Apparently we humans evolved to see the difference between those bound to us by blood and ethnicity and those not bound to us, and we share our scarce resources accordingly. The pity that the Samaritan feels is a consequence of evolution, a feeling that is adaptive when aimed at his children, kin and clan but dangerously irrational when it spills over toward a stranger.

The Samaritan violated the norms of genetic selfishness. First, he reached across an ethnic line that was very real in those days (Jesus’ audience would have identified the victim as Jewish). Then he spent his own money on the care of a stranger and even trusted an innkeeper whose reliability he hadn’t established. In the world of evolutionary psychology, the coins the Samaritan gave for the man’s care might just as well have been tossed into the sea for all the good they did his own genes (unless a fertile woman was watching and jumped to the conclusion that he was rich; seriously, people make this argument).

Most remarkably, Jesus concluded his parable by asking his interlocutor: Which of these three acted as a neighbor? Jesus left the door open to the sorts of rationalizations we make (rationalizations are another thing evolution made us good at) and asked the man whether he admired the example Jesus had put before him.

Jesus of Nazareth didn’t know anything about evolutionary psychology, but he knew all about danger and safety, selfishness and generosity, racism and prejudice. He knew how the movement of pity in our guts was confined and channeled to those people who could some day return the favor. He was very attuned to a world of humans who had evolved to walk on the other side of the road as quickly and discreetly as possible. Yet he invited his hearers to imagine whether that movement of pity might not open us to the humanity of the stranger, whether the powerful bond of love and obligation might also tie us together across ethnic lines, across family lines and across lines of safety. And just as important, he left his hearer to answer for himself: Are an ungoverned movement of pity and the bond that results worth embracing?