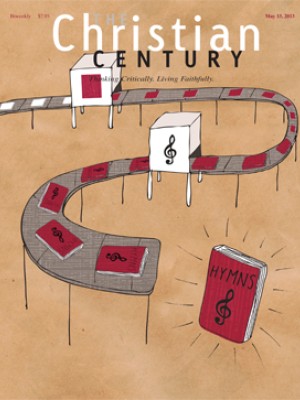

Singing from one book: Why hymnals matter

Read the sidebar article on the making of the new PCUSA hymnal.

Hymnals are more like telephones than automobile tires. Tires wear out visibly and require replacing. Telephones, on the other hand, seldom wear out, yet still get replaced when updated models offer new features attractive enough to warrant the change.

Like telephones, hymnals are built to last. Aiding their durability is the fact that they get limited outings (mostly on Sundays, often in the hands of gentle users). As physical books, even after 20 or 30 years their spines remain unbroken and their pages unwrinkled. Even more significantly, as collections of the church’s cherished songs, the hymnal’s contents may actually improve with the familiarity of age.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

Little wonder, then, that many churchgoers greet the announcement of a new hymnal with the puzzled, plaintive or even outraged question: Why? Why do we need new hymnals when the ones in our pew racks are still perfectly good? If “perfectly good” means showing no wear and tear, the question makes sense—all the more so if the person asking it is a stranger to the new features available in updated models.

Some of these features, as with telephones, involve technology. In the 21st century, hymnals appear not just as bound volumes but also as digital resources: e-books downloadable to the device of the user’s choice; projection editions with slides of words (or, in some instances, words and musical melody lines) for congregations that sing off a screen rather than a printed page; web editions with fully searchable indexes, audio files to hear what any given song sounds like and downloadable files of words and music to print as bulletin inserts. A 2008 product from LifeWay Christian Resources was cleverly promoted as “a hymnal without a back cover” because additional materials, whether made available online or on CD-ROM, could indefinitely expand the contents of the printed book.

But if changes in technology were the only developments prompting the next generation of hymnals, publishers could spare themselves the time- and resource-consuming processes of product development and simply digitize existing books, marketing the resulting websites and projection DVDs to tech-savvy congregations. Instead, over the past six years or so, denominations around the country have been creating whole new song collections. In 2006, both Missouri Synod Lutherans and the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America brought out new worship resources (the Lutheran Service Book and Evangelical Lutheran Worship, respectively). Following suit, the Southern Baptist Convention in 2008 published the Baptist Hymnal, whose title deliberately omitted the definite article to acknowledge the fact that another group of Baptists was at the same time creating Celebrating Grace (Mercer University Press, 2010). Responding to a new Vatican-mandated English translation of the liturgy, Roman Catholic publishing house GIA issued both Gather III and Worship IV in 2011. But 2013 will be the banner year: the Christian Reformed Church and Reformed Church in America project that their collaborative volume, Lift Up Your Hearts, will appear in June; the Presbyterian Church (U.S.A.) anticipates its collection, Glory to God, in September; the Community of Christ (renamed in 2000 from the Reorganized Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints) will launch Community of Christ Sings in October.

Even denominations deciding not to undertake complete new collections have recognized a need to make more recent materials available. In 2009, the United Methodists tabled a hymnal project due to financial constraints but began working instead on a smaller supplemental volume, Worship and Song (2011), containing 190 pieces of music rather than the 600–800 a full hymnal would include. In the summer of 2012, the General Convention of the Episcopal Church determined that a total revision of The Hymnal 1982 was not feasible but charged a task force with developing “a variety of musical resources” as a means of “enlivening and invigorating congregational song.”

So the “why” question about new hymnals and hymn resources will soon arise, if it has not already, from the pews in numerous denominations. Aren’t our old hymnals still perfectly good? What is driving this flurry of new publication?

Indeed, why a flurry of print publication at all? Granted that a denomination’s resources may need updating, could this not simply take the form of projectable downloads suited to our digital age? (To return to the telephone analogy: Why does anyone persist in using a landline when it seems to others a cumbersome relic of a bygone era?) While some publishers have discussed digital-only options for their new hymnals, most continue to elect a both/and rather than an either/or approach. A year-end report by the president of the Presbyterian Publishing Corporation in December 2012, for example, observed that roughly 20 percent of congregations anticipate ordering a web or projection edition of the 2013 Glory to God; this leaves 80 percent still relying on physical books or some combination of paper and projection formats.

Why a physical book in a digital age? Perhaps most prosaically it’s because copyright law has not caught up with the world of web- and projection-based products, and procuring copyrights for these products can prove more difficult than for print. So a book can contain materials that copyright holders will not release for digital use (or at least not without a prohibitively hefty price tag). In addition, books are portable and relatively immune to technical malfunction. They require no screens, projection equipment or trained audiovisual staff. Hymnbooks can thus serve as resources for retreats, outdoor worship, Sunday school classes, home and family devotionals—or occasions when the power goes out.

Furthermore, books enable the people holding them to see things that are more likely to be features of strophic hymns—texts that develop their themes across a series of strophes or stanzas—than of shorter form praise choruses: connections across stanzas (the fact that a hymn poet chose to use the same word to start the fourth line of each, for example), as well as the trajectory of a text (when it is at its midpoint and when it is drawing to a close). Also more in keeping with the traditions of standard hymnody, hymnals provide opportunities for reading and singing parts in a way that the projection of words only, or even of words and melody line, does not.

But there are other reasons for print volumes, reasons that are not restricted to the hymn (in contrast to the praise chorus) genre. Projection is ephemeral: now we see it, now we don’t. A book is a more lasting artifact, but it also subject to occasional wear and tear—exemplifying the embodiment we celebrate in the incarnation. Indeed, because books are tangible, couples or parents and children enjoy the intimacy of sharing the same physical object. An older person’s fingers can point out words or notes to a younger person—in ways that not only strengthen the intergenerational bond in worship but also help children learn to read syllables and recognize melodic shapes.

Finally, just as Bibles in pew racks give worshipers the opportunity to study the lessons of the day in context, so physical hymnals perform a comparable function for sung texts. Congregation members are not simply privy to the passages a worship leader has selected, whether in scripture or in song, but are exposed to the church’s fuller repertoire. Readers can discern relationships across hymns in proximity to one another (like browsing the shelves of a bookstore or stacks of a library—also diminishing, but not yet dead practices!). As worshipers turn the pages of a hymnal, they can encounter songs they know and love alongside ones they do not (or do not know yet). Some of these unknown pieces may even appear in languages they do not speak or read, reminding them of the diversity of the wider body of which they are members.

The mention above of praise choruses, in contrast to multistanza hymns, suggests a further set of reasons for the current boom in new hymnal production. In addition to technological innovations in format, over the past few decades three trends in content have vastly expanded the repertoire of materials available for congregational singing. The most apparent of these is, of course, the emergence of praise choruses out of the worship revival of the 1970s. Instead of traditional hymns, worshipers in the Jesus communes began writing their own songs—often using guitar rather than organ accompaniment and often featuring short, repetitive lyrics drawn directly from scripture.

Karen Lafferty’s 1971 paraphrase of Matthew 6:33 (“Seek ye first the kingdom of God”) was one of the first of this genre to catch on, initially in coffeehouses around Southern California and subsequently even in mainstream denominational hymnals. While factionalism ensued—the infamous “worship wars” in which some decried praise choruses as simplistic while others denounced traditional hymns as stodgy—the resultant revolution in congregational song has been undeniable. Congregations that worship exclusively with the praise song genre will continue, despite the flurry of new songbook publication, to download the latest examples off the web or to create their own new material week by week, without any need for a single updated resource. But congregations that prefer some blend of old and new stand to benefit from collections that contain the best of both worlds. The question for hymnal creators is not whether to include pieces from the “praise and worship” or “contemporary Christian” genre in their collections, but which pieces to include—which ones have demonstrated sufficient staying power to warrant publication in a volume intended to see 20 or more years of use.

Truth to tell, the impact of this revolution in song styles has brought even the word hymnal up for review. If a hymn is precisely defined as a strophic religious song that takes the form of multiple verses all sung to identical music (with or without a refrain, but generally with no bridge), then once a collection opens its covers to nonstrophic scripture paraphrases like “Seek Ye First,” the name hymnal is no longer fully accurate (a glance at the recent new worship resources mentioned earlier will show that only one of the nine uses the word hymnal in its title).

Other nonstrophic forms contribute to this puzzle over naming. While hymnals in the U.S. have long incorporated material from outside the English-speaking world—chorales from Luther’s Reformation (“A Mighty Fortress”), metric psalms from the Calvinist tradition (“All People That on Earth Do Dwell”) and carols from Poland (“Infant Holy, Infant Lowly”)—recent interest and excitement have focused on music from Africa, Asia and Latin America (ever since the 1983 Vancouver and 1991 Canberra Assemblies of the World Council of Churches). Just as songs from the praise chorus genre cry out for guitar accompaniment, this newly discovered, highly rhythmic music from the world church calls out for strong percussion. With some asperity, waggish blogger Grant MacDonald has suggested that one of the top ten reasons for using drums in worship is that they distract from the use of guitars!

That clever comment suggests that new worship music is not always greeted with as much enthusiasm by people in the pews as by those serving on editorial committees. An anonymous respondent to a recent survey conducted by one such committee suggested that all the “foreign songs” be put in a separate book, presumably for use by churches with a lot of “foreigners” in their congregations. But even if remotely desirable as a space-saving or cost-cutting measure, such ghettoization would be tricky. After all, when does a song count as foreign? Surely not when it has a sturdy Welsh tune or a set of lyrics translated from the German. Groups putting together 21st-century worship resources seem to share a conviction that words and music from other traditions and cultures belong in congregational song collections not because people from these other traditions and cultures are necessarily present in the pews on any given Sunday but because they are all children of the same God. Feeling the syllables and rhythms of “foreign” worship on the tongue and in the feet provides a regular, visceral reminder of the “wideness in God’s mercy” (to borrow a phrase from a good old Victorian hymn).

In addition to praise choruses and songs from parts of the globe less well represented by hymnbooks produced in the last quarter of the 20th century, a third trend in updated worship resources involves hymns of a traditional strophic form but with newly written texts, either to familiar tunes or original musical compositions. Some of these texts speak of current issues not much treated in earlier hymnody (from aging and Alzheimer’s to weaponry and welcome). Others lift up lesser-explored images and characters from scripture (the Ethiopian eunuch, the Gerasene demoniac, the woman who scours her house for a lost coin, the Samaritan woman at the well). Scholars acknowledge that the “hymn explosion” that began in Great Britain in the 1970s has given rise to the most active period in English-language hymn writing since the mid-1800s, in the United States as well as in England, Scotland, Canada and New Zealand. No contemporary volume (or digital resource) would be complete without evidence of this burgeoning creativity, a testimony to the ongoing work of the Holy Spirit in raising up poets to proclaim God’s word afresh in each new age.

Yet just as scripture admonishes believers not to quench the Spirit (1 Thess. 5:19), it also advises testing the spirits to see whether they are from God (1 John 4:1). In the recent explosion of praise choruses, global songs and topical hymns, not every new creation is equally meritorious, and publishing houses engage review teams of writers, musicians and theologians to assist in compiling denominational collections rather than leaving churches on their own to choose materials out of the vast sea of available (and highly variable) options. These review teams face questions ranging from the sublime to the (seemingly) ridiculous. How much Father, Lord and King language for God belongs in an “updated” worship resource; how much brother, son and man language for human beings? Do patriotic songs belong in a hymnal, and if so, which ones? Should 21st-century hymns use “thee” and “ye” language that went out of date in spoken English in the early 1600s? Can the church really endure another text that rhymes love with dove and above? Should pronouns for God begin with capital letters? Can people in the pews still sing a high E?

The best hymnal committees are those where members disagree in their responses to all the questions above (and countless others). Only vigorous debate across opposing viewpoints can assure that a new collection of congregational song will serve the needs of a diverse denomination and not just the preferences of a like-minded few. This approach to diversity means that the next generation of hymnbooks will be eclectic and wide open to a criticism of inconsistency: some texts will sing of the One who is “Father forever, Prince of Peace” and others of the “Womb of Life and Source of Being” (Ruth Duck) or “Source and Sovereign, Rock and Cloud” (Thomas Troeger). Martin Smith’s praise and worship song “Shout to the North” will include a stanza beginning “Men of faith, rise up and sing” but will balance it with one exhorting, “Rise up, women of the truth.” “O Come, All Ye Faithful” will retain the archaic pronoun; “You Servants of God” may not. A casual reviewer might view such discrepancies as evidence of haphazard editing. A more careful one might see them for what they are: hard-won compromises enabling an excitingly pluralistic people of God all to sing, literally, out of the same book.

In the current political climate, such hard-won compromises seem increasingly rare—and increasingly valuable. Not to be overly cute, but a hymnal is like a telephone in ways other than the fact that both bear replacing long before they physically wear out. Like a telephone, a hymnal is also a medium of communication to bridge distances and differences. Old hymns, psalms, spirituals and gospel songs serve to bridge generations far removed from each other, connecting today’s congregations with resources and relatives from centuries past. New songs build bridges, too, honoring the contributions of contemporary worshipers, whether from popular culture in the U.S. or from communities around the globe.

Most significantly of all, however, worship songs communicate the adoration of believers to the One who gave us breath and continues to inspire words in our minds and melodies in our hearts. Surely, far more important than pleasing ourselves with what we sing in worship is making a sacrifice pleasing to God. And that sacrifice just might mean setting aside our personal preferences in order to sing the heart songs of our neighbors, freshly available to us in new hymnals—even when the old ones have worn so well.