Saved by fiction: Reading as a Christian practice

Over the course of my life, I have taken on all manner of spiritual practices, from now-I-lay-me-down-to-sleep to centering prayer. I have prayed with the Psalms, with the rosary, with icons. I have picked up practices and put them down. Some still discipline and nourish my praying life.

But of all the spiritual disciplines I have ever attempted, the habit of steady reading has helped me most and carried me farthest. Of course, reading scripture has been indispensable. But reading fiction—classics of world literature, fairy tales and Greek myths, science fiction and detective novels—has done more to baptize my imagination, inform my faith and strengthen my courage than all the prayer techniques in the world.

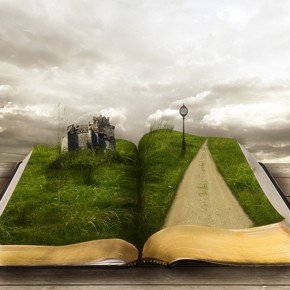

For as long as I can remember, even before I could read, I have loved books. The heft and smell of them, their implicit promise. The magical way they hold riches beyond measure, like chests of pirate gold. The way they open doors to other worlds. The house I grew up in had floor-to-ceiling bookcases in nearly every room, books piled on tables, books stacked in the hall and lining the stairs.