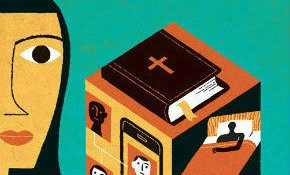

Training in Jesus’ way: Ministry in the 21st century

What is pastoral ministry like these days, and how is it being shaped in new ways? The Century talked to pastors about the challenges and surprises of their early years in ministry. This interview is the eighth in a series. Todd Friesen graduated from Associated Mennonite Biblical Seminary in Elkhart, Indiana. He is lead pastor of Lombard Mennonite Church in west suburban Chicago.

What excites you most about ministry these days?

Discipleship and spiritual formation. Jesus calls us to make disciples, not just converts. Discipleship means learning how to follow Jesus and obey his teachings, and Jesus taught us to do some really difficult things: forgive 77 times, feed the hungry, renounce violence, love our enemies, suffer for what is right. So we need regular and transforming experiences of God’s grace.

I believe that discipleship begins in communal worship. That’s where we encounter God and experience God’s lavish grace, where we are empowered for faithful living. Our spiritual formation deepens as we connect with one another in loving fellowship and supportive relationships. Our lives are reoriented as we train in Jesus’ ways, and we are then sent out to share the love of Christ.