Sent to serve: William Willimon on being bishop

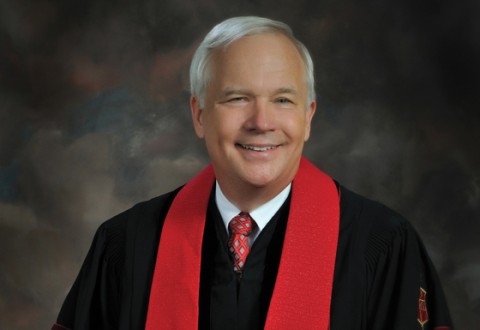

Widely published author and preacher—and Century editor at large—William H. Willimon will step down this summer after eight years as bishop of the North Alabama Conference of the United Methodist Church. He will return to teaching at Duke Divinity School, where for many years he was dean of the chapel and professor of ministry. I asked him about his experience as bishop and some other topics.

As you leave the episcopacy after eight years, what do you consider your greatest achievement?

Perseverance. That’s a cardinal virtue for any form of ministry, including the episcopacy—the willingness to serve where one is sent with the conviction that God is present, working through your ministry to accomplish God’s purposes, even when one doesn’t get observable results.