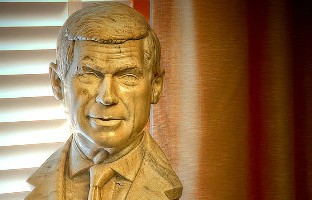

The peaceable senator: Mark O. Hatfield, 1922–2011

In the midst of today's rancorous politics and the

trivialization of religion in the public square, the death of Mark O. Hatfield

on August 7 called to mind a different kind of political style and a different

kind of Christian political witness.

When Hatfield entered the U.S. Senate as a Republican from

Oregon in 1967, the Vietnam War hung over the nation like a dark cloud. He had

already registered his opposition to the war by casting the lone vote against

Lyndon Johnson's policies at the national governors' conference. He joined

Democratic Senator George McGovern in 1970 to introduce legislation to cut off

funds for the war. Following President Nixon's invasion of Cambodia that year,

that legislation became the political focus of the antiwar movement.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

Hatfield's evangelical Christian convictions and his

opposition to the war made him an unusual and controversial figure. At one

point, he was prohibited by the president of evangelical Wheaton College from

speaking at the school's chapel service. He made an indelible impression on an

emerging generation of young evangelicals who were searching for models of

faithful political action. Hatfield gave a powerful witness not only in opposing

the Vietnam War but in addressing issues of social justice and the global

division between rich and poor. When he read the first issue of the Post-American, the precursor to Sojourners, he immediately sought out

the editor, Jim Wallis. In 1973 he supported the Chicago Declaration of Social

Concern, a watershed statement by 40 evangelical leaders declaring their

Christian commitment to work for social justice.

A few years ago, I was in Kenya for a gathering of the

Global Christian Forum. When we gathered in small groups to share our journeys

of faith, I spoke of my work with Senator Hatfield. The face of a Kenyan

university professor and Christian leader suddenly lit up. "Mark Hatfield! I

have read his books and followed his story. He's the one who inspired me in my

Christian life and political work!" That story could be repeated thousands

times by students, pastors, activists, professors and politicians.

Hatfield was described by some at his memorial service as a

pacifist—a rather amazing label for a man who was a U.S. senator for 30 years.

It's a description he didn't publicly claim for himself, but he did find the

case for nonviolence in following Jesus compelling. I recall how he probed

those ideas with John Howard Yoder, author of The Politics of Jesus, during a lunch in the Senate Dining Room.

Warning constantly of the dangers of uncontrolled military

spending, Hatfield led a group of senators in challenging new weapons systems

proposed by the Pentagon in the 1970s. In 1982 he joined with Ted Kennedy in

proposing a nuclear arms freeze. Incredibly, he never voted in favor of a

military authorization bill, consistently protesting the escalating

expenditures for national defense—a voice all but lost in today's political

debate. His personal conversations with Billy Graham were a factor in

persuading the famous evangelist to take a public stand against the nuclear

arms race.

Defying predictable categories, Hatfield was also a strong

supporter of legislation to prohibit abortion. I remember Hatfield discussing

with Harold Hughes, the antiwar Democrat from Iowa, how Christian witness

should mean opposing all forms of violence against life. It's ironic that

perhaps the most prominent politician in recent decades to support the

"consistent ethic of life" advocated by Catholic social teaching was himself a

Baptist.

Committed to principles and his core convictions, he also

understood the tradeoffs necessary to get things done. When looking for votes

to cut off funds for the Vietnam War, he turned to Henry "Scoop" Jackson, a

prominent hawk and influential Democrat. At the time, Jackson was seeking

federal funding for the supersonic transport aircraft, which he thought could

revive the sagging fortunes of the Boeing Company, based in his home state of

Washington. Environmentalists and others were strongly opposed to the SST, but

Hatfield (and McGovern) privately offered to support the program if Jackson

would endorse the antiwar legislation. Jackson wouldn't agree. The

McGovern-Hatfield measure fell a few votes short.

What other senators and colleagues remember most about

Hatfield was his compassion and constant willingness to seek bipartisan

approaches that served the common good. Bill Clinton once said, "Mark Hatfield

loves his enemies, and so he has no enemies." In contrast to the adversarial,

partisan attack mode that has become ingrained in political behavior, Hatfield

always wanted to extend a hand rather than shake a fist. Without similar

examples today, our politics will continue to degenerate into pugnacious rituals

that paralyze possibilities to serve the common good.

Hatfield's civility was nurtured by faithful participation

in a weekly Senate prayer breakfast group. He believed that personal

relationships should transcend partisan and political divides, and he saw those

relationships as a key dimension of his own Christian discipleship. The circles

of that fellowship proved to be a key source of support in Hatfield's own times

of political and personal crisis.

Yet Hatfield was wary of attempts to use religion to give a

patina of righteousness to political power. Speaking at the National Prayer

Breakfast in 1973, with President Nixon on one side and Billy Graham on the

other, he said, "If we as leaders appeal to the god of civil religion, our

faith is in a small and exclusive deity, a loyal spiritual Adviser to power and

prestige, a Defender of only the American nation, the object of a folk religion

devoid of moral content." Speaking against the backdrop of Vietnam, Hatfield

said that "we must turn in repentance from the sin that scarred our national

soul." Few of his speeches received such widespread attention as this one did.

His prophetic words touched many people—and solidified his position on

President Nixon's "enemies list."

When the religious right emerged, Hatfield called it an

"embarrassment." His sharply contrasting approach can be glimpsed in this

passage in Between a Rock and a Hard

Place: "Radical allegiance to Jesus Christ transforms one's entire

perspective on political reality. Priorities become totally changed; a whole

new understanding of what is truly important bursts forth. There is an

uncompromised identification with the needs of the poor and oppressed. One is

placed in fundamental opposition to structures of injustice and forms of

national idolatry. Further, there is a commitment to the power of love as the

only means to the end."

Hatfield worked hard to live up to those ideals. His way of

joining faith and politics remains a powerful example, one needed these days

more than ever.

Granberg-Michaelson served on Mark Hatfield’s staff from 1968 to 1976.