Presidential limits

These are frustrating times for Americans who believe that their government should actively promote employment, equality and social welfare. Elected officials are disinclined to kick-start the fragile economy. The Obama administration remains cozy with the financial industry. And President Obama's signature accomplishment—health-care reform—is under continual threat in the courts and in the states.

Some blame a lack of conviction or leadership on Obama's part. Others point to congressional Republicans' intransigence and irresponsibility. The president's approval rating is at an all-time low; so is House Speaker John Boehner's.

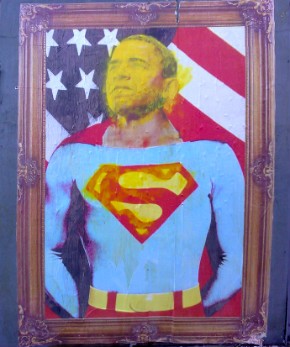

In this issue, Robert Westbrook examines Obama's failure to follow in Franklin D. Roosevelt's footsteps by seizing the opportunity for large-scale reform amid crisis. Among other things, Westbrook explores Obama's limited progressive vision, his "pragmatic minimalism" and the fierce Republican opposition. These aren't mutually exclusive explanations for the problem, and they share a common theme: it's a mistake to place too much hope for justice and equality in President Obama.