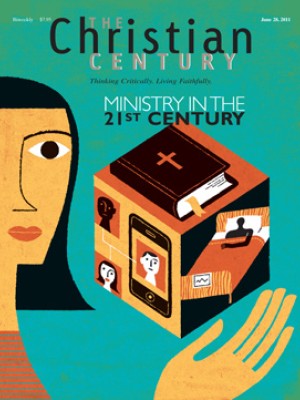

Deeper history: Ministry in the 21st century

What is pastoral ministry like these days, and how is it being shaped in new ways? The Century talked to pastors about the challenges and surprises of their early years in ministry. This interview is the first in a series. Josh Carney is a graduate of George W. Truett Theological Seminary at Baylor University in Waco, Texas. He serves as teaching pastor at University Baptist Church, about a mile from Baylor's campus.

What excites you most about ministry these days?

Our church's growing diversity. University Baptist Church started with a mission to reach college students, underchurched and overchurched alike. We've maintained this goal but have also increased our efforts to reach our more immediate neighborhood, which is lower-middle class and ethnically diverse. These two pieces have come together to shape our mission.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

In the book of Revelation, the eschatological victory choir is made up of people from every tongue, tribe and nation. If the takeaway is that the future kingdom is diverse, then it's also exciting to see our community embrace age diversity in new ways.

What are overchurched college students like? What challenges do they pose for ministry?

They're students who went to church their whole life without really knowing why. It seems we have a lot of students who were either taught good theology but had no praxis to accompany it or vice versa. When people are exposed to the repetition of liturgy—and all churches have some kind of liturgy—without understanding why, they often get frustrated or lose interest.

What has the transition toward more age diversity been like? Any bumps?

It's been exciting. My heartbeat is for families, and as this group grows it presents an opportunity to get to know and love more people. The major hurdle has to do with congregational identity. An increase in families means a need for more resources for them, and when we shift resources we make statements about mission and identity. We are trying to figure out who we are in a way that both affirms the historical and makes room for the new.

The family demographic also presents logistical bumps requiring different problem-solving methods than we've used in the past. We used to deal with obstacles very organically. We'd identify a problem, give it a small boost and wait for creativity to solve it. If we had 20 new college students all interested in yoga, we'd identify a yoga leader and give them a meeting time and space. All of a sudden we'd have a new group. But now we have 20 new babies, and you can't exactly throw them together in a room and pick a leader to solve whatever problems arise. We've had to give such things more thought than our old laissez-faire approach required.

What other parts of being in ministry have been challenging?

Working out how specifically to pursue our mission as a church. It hasn't been difficult for us to identify how God would have us be kingdom people in the world. What's been harder is determining the best way to accomplish this. For example, we might all agree that the kingdom that Jesus proclaims compels us to work to alleviate suffering. But what is the best, most responsible way to do this?

Is the debate about prioritizing what kinds of suffering to address? Or about direct service versus systemic change?

Both. Because we're close to a university, we've had to learn that on just about every issue—theological or otherwise—our community is full of opinions that are both extremely educated and extremely diverse. A lot of people have had experiences that shape the way they see the world—and what they think the solutions for the world's ills are.

The challenge is to engage and serve the world in a distinctively kingdom way. Instead most of us quickly let our political ideology dictate how we do this. We need to continually pray that the Holy Spirit would illuminate the countercultural love option that Jesus offers—the third way that comes through gospel imagination.

What's something important you've learned in ministry?

What's something important you've learned in ministry?

As the world changes, people don't. Folks do lots of things they didn't do ten years ago: carry iPhones, send Facebook messages, buy fuel-efficient cars. But people are hurt the same way and need the gospel the same way they did ten years, 100 years or even 2,000 years ago.

There is much within evangelical culture that is now seen as unhealthy and misguided. We at UBC have rejected much of our immediate past. In the constructive phase, the natural tendency seemed to be to look back further by exploring the liturgy of the church. Here we found much that was helpful—and we found that some of our objections had already been addressed.

Slowly, we've begun to reidentify what was useful about our immediate, painful pasts as well. It's been refreshing to create new liturgy and find gifts from all of the church's seasons.

Has this process of exploring the past been largely about worship and liturgy, or has it touched other areas of the church's life as well?

I'd say that all the changes we've experienced have fallen under the umbrella of ecclesiology. A pastor friend says that everything comes down to ecclesiology, and the longer I do this ministry, the more I agree.

How have pastors and others with more experience been helpful to you? Or unhelpful?

In Waco, there's no lack of Baptist heritage of a southern flavor. We have benefited from the wisdom of many who have been at this longer than we have. In times of need and ecclesiological formation, key players from this community have spoken to us in ways that proved extremely helpful.

There is a flip side to that coin. When UBC met for its first service in 1995, hundreds of students showed up, many in response to flyers handed out at fraternities and sororities. It was evident that the church was addressing a glaring need. It'd be an overstatement to call it envy, but other church leaders in the community immediately recognized that doing church differently has its benefits. Success is naturally attractive. Some church leaders reached out to try to bring the congregation under their wing. They were kindhearted folks, but they didn't necessarily understand what was different about UBC.

What does your denominational affiliation mean to you and your parishioners?

I don't think most folks who walk through our doors could tell you much about the Baptist General Convention of Texas or the Cooperative Baptist Fellowship, nor could they articulate Baptist polity. Personally, I have a growing appreciation for Baptists, and I love the free tradition. But I also have a growing appreciation for the high-church tradition. One of the reasons I like being Baptist is that our tradition allows us to implement the best from both worlds.

On the basis of your ministry experience so far, what would you change about your seminary curriculum?

That's an intriguing question. First, let me express my deep appreciation for the many things that Truett is doing right—as well as to acknowledge that some changes would simply require more funding and a larger faculty.

A professor of mine says that the seminary curriculum's breadth is both its strength and its weakness. I can't think of one class I took that hasn't proved helpful. But I do think that seminaries need to continue to examine the ever-changing landscape of ministry—and to tailor programs that give students more chances to specialize.

I didn't have an ethics class at Truett. That would have been helpful—especially for me as a teaching pastor, a role that involves a lot of epistemological activity. I also wish I had taken a hermeneutics class. It's one thing to study the historical-critical method and affirm it as the proper place to begin. But what's the best way to move from exegetical findings to situational context? Postmodernism has reached deep into all facets of life, making a Christ-centered, pneumatologically driven hermeneutic all the more important.

What writers have shaped your understanding of ministry?

Greg Boyd shaped my views on theodicy, God's character and spiritual warfare. N. T. Wright's work on soteriology offers exegetical help that I have not found anywhere else—he and Richard Hays are probably my favorite New Testament people. For Old Testament, I'd say Terence Fretheim and Walter Brueggemann. Reading Brueggemann is like skating on butter.

How about your personal heroes?

My three pastors.

My dad, Terry Carney, provided an 18-year internship. He pastors a charismatic church in northern Wisconsin, a church filled with Flannery O'Connor types of characters. Though we differ in some ways theologically, I'm forever grateful for all that he taught me about the Holy Spirit. This forced me to fuse all that I've learned with who God is; it kept the classroom from becoming abstract. My dad's also been ministering in the same spot for 25 years. In an age in which church growth and celebrity are celebrated at the expense of an emotionally healthy community, I admire his faithfulness in a sometimes thankless environment.

I studied with Greg Boyd at Bethel, and I was a member of Woodland Hills Church, which he pastors. Greg taught me how to think, as well as why theology matters. He is one of the most gifted communicators I have ever heard. Each week he would reach inside me, grab my soul, hang it in front of my face and make me ask, "In what new way does God lay claim to my life?"

Kyle Lake was the teaching pastor here at UBC before me. He died in 2005, in a tragic electrocution accident involving our baptistry. I knew Kyle only for a year, but I had the great privilege of inheriting his ministry. My work includes helping the church grow theologically, especially ecclesiologically—and I do this standing on the foundation that he built. His death also forced me to wear the theodicy I was confessing.

What was that theodicy, and what did it look like to wear it?

There's no shortage of lay theologians willing to offer commentary on tragic situations. When Kyle died, we heard a lot that was compassionate and generous but also a lot that was theologically misinformed, even hurtful. In moments like that, you ask yourself what you really believe.

On the first anniversary of Kyle's death, our community met by his graveside for a brief memorial service. "A lot has been said this year about Kyle and God's role in his death," said his dad, who had endured many of those mean-spirited comments. "We believe that electricity and free will happened last year." The belief that God did not take Kyle's life as part of some larger grand plan permitted us to embrace the idea that God weeps with those who mourn.

What does being a "leader" mean? Has your understanding evolved?

My friend and copastor Craig Nash recently articulated something I had long been feeling: an aversion to the word leadership. Christians are often eager to develop leadership models and analyze leadership styles; it's an area in which the church continues to follow the world's lead. Lead pastors who can run an organization effectively are tagged as good leaders.

Again, the problem is that we've lost our gospel imagination. The CEO kind of pastor may be an effective leader, but I'm not sure this is how the church is to be led. I think good leadership is defined by Jesus with a towel in hand, washing feet. And that's also each Christian's call. We are to be disciples who mimic Christ by loving self-sacrificially. What does this mean for pastoral leadership? It means that you pick up a cross and ask your congregation to come with you.

Where do you go for inspiration?

I find fiction helpful when I can stay with it, but often I am drawn back into reading New Testament scholarship instead. When I do housework on Saturdays I listen to podcasts—maybe Krista Tippett's if I think I'll like her guest. I really enjoy this time.

What other podcasts besides Tippett's?

Sermons: Greg Boyd, Rob Bell and Shane Hipps. I also subscribe to the Truett podcast, which gives me a chance to hear from friends, professors and others from the Waco community.

How about collegiality and renewal? Where do you look?

There's a group of pastors that I meet with once a month. They have been a great encouragement.

What's the nature of this group—sermon study, professional support, personal fellowship?

Mostly professional support. We spend the first half of our time eating together and checking in. Then we take turns presenting case studies from our own experience. Sometimes we offer feedback, sometimes we mourn together, but we always learn together.

I'm also very fortunate to have co-workers and parishioners who are my friends. That's an advantage my dad never had. The people I pastor are extremely mature, and they permit me to be both pastor and friend.

Any ambivalence about this? Some people think that it is a bad idea for pastors to regard parishioners as friends.

I understand the biblical narrative as saying both that God calls leaders to lead and that we are a priesthood of believers. I let these ideas hang in tension. As committed as I am to free-church Protestantism, I recognize that there is something valuable about the uniqueness and function of a priest. When people have children in the intensive care unit, they want a priest. When people lose a loved one, they want a priest. When chaos looms large and countries are in crisis, people want a word from their priest.

But people also want to know that their pastor is a real person—that their pastor is exhausted by caring for children, worries about monthly budgets from time to time and struggles to be a disciple of Jesus. I have found that friendship is the one relationship that permits me to play both of these roles in people's lives.

Back to the subject of inspiration and renewal generally: the most important thing I do is be consistent about leaving the office at five and leaving work there. The couple of hours I have at night with my wife and children are the best part of my day. I work hard to protect that time, because it is very life-giving.

What's your sermon preparation process? What resources do you find helpful?

On Monday I spend an hour reading the biblical text, first lectio divina and then critically. Then I jot down all my questions and notes about it: Which words are inspiring? Where is there movement within the text? What does this matter to UBC?

After that I make copies of three or four commentaries to keep with me all week. I spend most of Monday reading, and I might spend some time with the original language of the text. I try to do meetings and other things on Tuesday so that the information can stew. The most important part is sitting with the text.

On Wednesday I determine how I am going to move through the text, and I divide the sermon's movements either by verses or by ideas. Then I fill in all the exegetical data I want to use in each section, at which point I've begun to craft the overall flow.

Thursday is given mostly to illustrative material and coordinating with our media director. And after all of it is done and the sermon is in front of me, I write my conclusion.

That's a pretty heavily exegetical approach. Do you stick mostly with that model?

Yes, especially when I'm preaching on the lectionary. These sermons are fairly narrative or inductive in form—I try to detect where the text goes and be faithful to that. If I'm not in the lectionary it's probably because I'm addressing something specific—I've found the text within the narrative that permits me to address the idea deductively. Either way, I try to fill the sermon with as much historical-critical data as possible without making it boring.

The homiletical moment is obviously a pastoral one, but the journey toward the apex of a sermon ought to include data that inject context into the moment. So I think effective sermons embrace both historical-critical and reader-response approaches.

What developments would you like to see in your congregation's mission? In the wider church's?

I hope that the church—both our local expression and the larger one that we're part of—learns to be more creative. I feel that a lot of our problems come from a lack of imagination.

When the pesky Pharisees try to trap Jesus by asking if he thinks they ought to pay the temple tax, he offers one of those answers that turns the question on its head. Caesar's image is on the money, so it belongs to him. Render unto Caesar what is Caesar's and to God what is God's. But what has God's image on it? Well, we do. The creation testifies about God. In fact, the creation exists because God breathed it, and all of this creation belongs to God.

Jesus both critiqued the world and loved it. He was never satisfied to give a response that lived within the parameters of the question. He found a better way, a third way to respond—and the world stood in awe as it saw God move within history. Our lack of this kind of imagination is evident in our politics, in our wars and unfortunately even in the church. But this can change. My prayer is that Christians will be imaginative Jesus people.

Describe an experience that made you think, "This is what church is all about."

A lot of what I've said so far is about the church's immanent ministry, how it engages the world. But this has to be rooted in transcendent ministry, in the worshiping community.

One Sunday at UBC the last song the band played was the doxology. It was time to make the transition to the learning portion of worship, but something within me was profoundly content to sit in God's presence. I found myself standing in the peace of God which transcends understanding, filled with an inexpressible joy and overwhelmed by love.

All the community gardens, mission trips, relationships with local school districts and low-income housing complexes—if all that work is not about this kind of moment, if it's not about participating in the divine dance that has been going on for all eternity, then it misses the point. We are because God is.