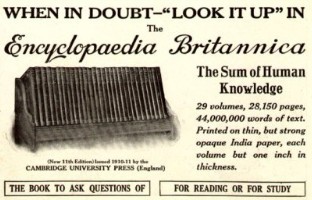

The great EB

This spring marks the 100th anniversary of the 11th edition of the Encyclopædia Britannica, generally considered the greatest manifestation of the "Great EB." In March 1911, a full-page ad in the New York Times heralded the 11th edition as "the sum of human knowledge—all that mankind has thought, done or achieved, all of the past experience of humanity that has survived the trial of time and the ordeal of service and is preserved as the useful knowledge of today" and declared that in its 29 volumes "all is included that is relevant and everything explained that is explainable."

Such claims on the part of any reference work, whether wiki-based or peer-reviewed, sound extravagant today. We are humbler now, less sanguine about our powers of comprehension, more sensitive to cultural bias. Yet there remains something awe-inspiring about the Great EB and the grand synthesis it represents. If there is folly in the attempt, perhaps it is a holy folly.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

The first edition, published in three volumes in 1768, was Edinburgh's answer to the French Encyclopédie. The three Scots who conceived the plan—diminutive Andrew Bell, prudent Colin Macfarquhar and whisky-loving William Smellie (memorialized by Robert Burns for his "uncomb'd grizzly locks, wild staring, thatch'd / A head for thought profound and clear, unmatch'd"), and the "Society of Gentlemen" which supported their venture, were after something more Scottish in spirit than the jaded rationalism of the French encyclopédistes. They hoped to distill all the arts and sciences to their essentials, retaining everything that is useful and pleasing in the world of learning and compassing the practical as well as the high arts, from the mechanics of Noah's ark to the physiology of childbirth illustrated in meticulous (to some readers, obscene) detail.

Subsequent editions enlisted the leading lights of British, Irish and eventually American learning and culture. But the 11th edition (which was updated but not significantly changed until the 14th) surpasses all. It gave T. S. Eliot a source of arcane lore at once fascinating and oppressive; in his poem "Animula," "The pain of living and the drug of dreams / Curl up the small soul in the window seat / Behind the Encyclopaedia Britannica." Jorge Luis Borges spent his first literary prize on a complete set of the 11th edition, and in "Tlön, Uqbar, Orbis Tertius" wrote of an imaginary world whose existence he discovered in an altered reproduction of the tenth. Richard John Neuhaus, who used to read the 11th edition every summer with his friends in an Ottawa cottage, counted it indispensable.

We purchased our own set many years ago, and it has been moldering away in the basement—with its dark red boards, morocco leather spine and India paper leaves slowly yellowing and gathering dust—ever since I gave up the scheme of reading it from end to end. To celebrate the centenary, our boys carried the heavy volumes back upstairs; and now I sit gazing at towers of knowledge I cannot hope to scale.

The 11th edition is the consummate expression of the heroic age of discovery and translation, of prodigies like Assyriologist Archibald Sayce and Egyptologist Flinders Petrie, of clergy naturalists, philologist missionaries, spiritualists, feminists, abolitionists, socialists, Tractarians, Darwinians, utilitarians and Theosophists. Dipping into the 11th edition at random, I encounter Algernon Swinburne discoursing on Mary Queen of Scots, Frank Podmore on automatic writing, James Clerk Maxwell on capillary action, Morris Jastrow on astrology, Baron von Hügel on the Gospel of John, T. H. Huxley on biology, James Legge on Confucius, Cuthbert Butler on Benedictines, G. G. Coulton on celibacy, John Muir on Yosemite, Reynold Nicholson on Sufism, Bertrand Russell on geometry, Jessie Weston on King Arthur, Laurence Austine Waddell on Tibet. I feel as if I've wandered into Socrates's afterlife: a chance to meet the intellectual heroes of the past, a symposium with men and women of genius, strong prejudice and strange habits.

Neutral is one thing the Great EB was not. Catholics felt misrepresented; atheists suspected Jesuit influence. Later editions were zealous about avoiding giving offense; but I find the clash of opinions bracing and am content to hear F. C. Conybeare say of the Eucharist, "To the modern mind it is absurd that an image or symbol should be taken for that which is imaged," knowing that I can turn to the articles on transubstantiation, Sacred Heart and Immaculate Conception for a different point of view. At least religion is taken seriously and theology conceived as a vital branch of knowledge.

At a 1968 banquet in London's Guildhall celebrating the 200th anniversary of the Britannica, Robert Hutchins raised his glass of Madeira to the mayor, prime minister and distinguished guests and toasted the Britannica as the embodiment of "a vision in which science and technology, instead of threatening to exterminate us, will repeal the curse of Adam and enable all men everywhere to achieve their full human possibilities." No doubt there is hubris in thinking that by adding knowledge to knowledge we attain wisdom. Yet I find too much of the true, the good and the beautiful in these 100-year-old volumes to return them to the basement. Somehow we will find a way to make room for them where they belong, next to the The Divine Comedy and the OED, on the first floor.