How the church grew in south Sudan

"They shall all be left to the birds of prey of the mountains and to the animals of the earth. . . . At that time gifts will be brought to the Lord of hosts from a people tall and smooth . . . whose land the rivers divide, to Mount Zion" (Isa. 18:6–7).

On my recent sojourn in southern Sudan, I learned that in the view of the Christians of the Episcopal Church of Sudan, Isaiah 18's description of the sufferings of a people "tall and smooth" refer to them. (Manute Bol, the late Sudanese professional basketball player, was seven feet, seven inches tall.) Suffering came to the people of southern Sudan when President Omar al-Bashir in the predominantly Arab-Muslim north sought to impose Islamic Shari'a law—an effort that sparked a southern uprising and years of civil war. Isaiah's reference to the "gifts brought to the Lord" is taken by the Sudanese churchpeople to mean the mass Christianization of the south; in the midst of civil war the ECS grew from a fledgling missionary enterprise to a church of 5 million (that's twice as many Episcopalians as there are in the U.S.).

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

From one vantage point this interpretation of Isaiah can seem arbitrary. Fundamentalists in the U.S., for example, sometimes argue that the "land of whirring wings" in Isaiah 18 refers to Apache helicopters and therefore to coming events in the U.S. But looked at another way, the Sudanese Christians' explanation of the passage may be true historically; Ellen Davis of Duke Divinity School says that the Dinka (or Jieng) people of southern Sudan likely were the southernmost Africans known to the Israelites. The Sudanese interpretation also places the south's Christians in the midst of a biblical drama with a cruciform shape of suffering and redemption.

Philip Jenkins has argued that Christianity's future is an African one. If so, what does the area that is poised to become Africa's newest independent nation tell us about Christianity's future?

The people of Sudan have lived with war virtually from the time of independence from Egypt and Britain in 1956 until the signing of a Comprehensive Peace Agreement in 2005. (There was a period of relative peace from the early 1970s to the early 1980s.) President al-Bashir and his predecessors in Khartoum have pursued a policy of Arabization—including the imposition of Shari'a—in an effort to unify their massive and unruly country. Revolting against these policies, the south sparked a civil war that has left some 2 million southerners dead since 1983. The growth of the Sudanese church amid the conflict is remarkable indeed. (The International Criminal Court has charged al-Bashir with war crimes, crimes against humanity and genocide.)

When foreign missionaries were expelled from Sudan in 1964, they left feeling that their efforts had been wasted. They had made few inroads into the cattle-based culture with its polygamous households and indigenous animist religions. Missionaries had tried to draw converts away from a practice of cattle sacrifice to the jak (local gods) and introduce them to Western-style education, literacy and worship. Their approach eventually worked—but only by accident, as it turned out.

During the decades of civil war, many southerners sought refuge in Khartoum, Cairo, Beirut and other Arab metropolises. They found themselves isolated from their traditional land and their herds. Western-style institutions for education and worship strengthened southern Sudanese solidarity during this time of exile, and embracing Christianity became a way to reject both enforced Arabization and English colonialism. When these exiles returned to their land, they swelled the ranks of the churches. The Diocese of Bor, for example, had only four parishes and four priests in the early 1980s; a decade later it numbered 230 parishes and 120 priests. The charismatic bishop Nathaniel Garang of the Bor Diocese is reported to have confirmed 10,000 people in a single day.

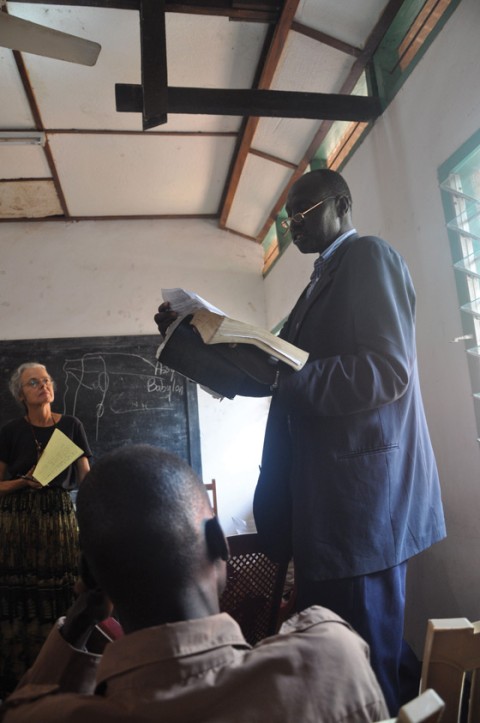

So unlike the situation of churches in the West, Sudan has the problem of catching up with church growth that has spun out of control. ECS bishop Ezekiel Diing of the Diocese of Twic East compared church growth in Sudan to the parable of the sower. "The seed," he said to me, "was thrown and reached everybody. Now we have to prepare ministers after the fact, and work more carefully to sustain the church from generation to generation."

The church hopes that New Bishop Gwynne College (NBGC) in Juba—the leading Anglican college of the five in Sudan—will be a foundation for a future university in Juba, the south's regional capital. There are signs of strength: the college is building a new and improved campus, it has dedicated students and a stable faculty, and enrollment is up this semester. But to call its facilities humble would be generous. The electrical power works only occasionally, as does the plumbing. The bathing stalls are outdoors. Students live in rooms designed to be faculty offices. Interim administrator Trevor Stubbs told me that the school loses money on every student enrolled. Students pay 750 Sudanese pounds (about $500) per term, yet in return they expect room, board, health care and spending money—the result being a net loss for NBGC. And squatters are an impediment to the progress being made with building construction.

Other Episcopal colleges in Sudan are in worse shape. One of them relies on donors for more than 90 percent of its income. Another holds classes near a trash dump that reeks and poses health hazards. When a wealthy American donor was late with her contribution, one school had to borrow money from its own diocese just to function. In the mid-19th century, missionaries talked about the need for an indigenous church independent of foreign donors. Such a church is still pretty much a pipe dream.

Despite its financial woes, the church is primed to play a key role in what the people of the south hope will soon be the new country of Southern Sudan. A referendum on independence is scheduled for January, and the anticipation of the birth of a new nation is palpable. But many fear that mutual hatred of the north is all that's holding the tribes of the south together and that once their mutual enemy is out of the picture, ancient tribal enmity may take over among the Dinka, the Nuer and other ethnic groups. And although the situation in southern Sudan is relatively calm now, whether the referendum is actually held may depend in part on whether the conflict in western Sudan's Darfur region is resolved. Fierce fighting continues there despite the 2005 peace agreement, with more than 300,000 killed and almost 3 million driven from their homes.

The church could be the glue that holds a newly independent south together. Indeed, church and state seem as fused in southern Sudan as they were under Emperor Constantine. I heard priests and bishops extol the south's liberation from northern tyranny with biblical references, from "Let my people go" to the star of Bethlehem—which is on the flag of "New Sudan," as some southerners call their gestating country. When I complimented one church leader on his vehicle, I was told it came courtesy of the south's government. Political leaders occupied the front row of both church services I attended, and at the service at Juba's Emmanuel Parish, one of them was given worship time to deliver an impassioned political speech. NBGC professor Simon Lual Bang, preaching at Juba's All Saints Cathedral one day, argued that the country would be better off if the politicians were less corrupt. Some politicians were sitting in the front row there too, but they only laughed and nodded.

More worrying is the widespread uncritical praise of the government of southern Sudan and of the Sudan People's Liberation Army, which fought for southern independence. SPLA leader John Garang is spoken of as a martyr, as are the 2 million war dead. "The SPLA soldiers are the greatest rebels in the world," one priest cheerily told me as we watched the army on parade. But Garang was hardly a holy man; the SPLA's human rights record is far from pristine; and much of the killing was the result of intertribal violence and internecine warfare within the SPLA.

I heard stories about pastors on the take from the government in Khartoum as secret agents, about others causing schism or enriching themselves from church coffers, and about a bishop who is not even living in his own diocese and so is failing to carry out what he was consecrated to do.

Despite the economic and political challenges facing the ECS, the level of theological discussion I observed was remarkably high for church leaders who have little formal training. In one such discussion, someone asked why God would allow Christian Sudanese to suffer so. A young man who was eager to attend seminary suggested that it was because the Sudanese didn't listen to the missionaries who first preached to them. But others disagreed. Simon Lual argued that tribes like the Dinka have often trusted in the power of war. "God doesn't curse people" but rather gives humans freedom and lets sin be its own punishment.

Bishop Diing weighed in, citing Jeremiah as an argument that God punishes like a parent who rebukes her children. A priest named Joseph Taban Lasuba objected to the notion that God is punishing Sudan for anything at all. "The Bible says all fall short and sin. Looking around, there are more wicked nations than ours that go unpunished. Aren't we rather victims and not only sinners?" Others pointed out that in a time of peace and greater prosperity, the churches aren't as full as they were during the war. They wondered whether adversity might be a strange sort of gift.

The ability of the Sudanese to see their own lives in light of the Bible often makes for breathtaking exegesis, such as their reading of Isaiah's reference to a people "tall and smooth." The Sudanese also sometimes see their leaders in the shadow of biblical history. Bishop Elinana Ngalamu, the first indigenous ECS archbishop, was buried behind the cathedral in Juba—but only after being exhumed from his first burial site in Khartoum. "It's like Joseph in the Bible," Joseph Taban told me. "We won't even leave our leaders' bones behind in the north" (Josh. 24:32).

Several church leaders insisted that when they and their people were on the run from government soldiers, they were miraculously spared injury from snakes and wild animals—just as the psalmist and Mark 16 promised that believers would be. Bishop Hilary Adebe of Yei comes from a diocese that experienced its own exodus. In the mid-1990s, when SPLA leaders forced Yei's people to leave, the Episcopal bishop and his Catholic counterpart gathered thousands of people and walked with them into temporary exile. Not surprisingly, there was much suffering from disease and anguish as a consequence of the displacement. But church leaders insisted, "Don't worry, God is in control, and the war is going to end."

"This enabled growth in miraculous terms," says Bishop Hilary (as Adebe is called), "and when people came back, the church was already there," waiting for them (unlike the foreign-based NGOs who left and didn't return).

Archbishop Daniel Deng Bul Yak, the primate of the ECS, told me that his favorite book of the Bible is Leviticus. In fact, Leviticus has had such appeal for people in southern Sudan that European missionaries often refused to translate it. What need would there be for people to convert to Jesus if they felt they had found all they needed in the Old Testament?

Ellen Davis says she once mentioned on a visit to Sudan the common taboo against eating a cow that has been dishonorably killed—for example, by being gored—and her Sudanese listeners shuddered with disgust. They understand and appreciate the letter of Leviticus law much more than Westerners do.

"It's a lively book to us," the archbishop said, "because it shows the movement of God with our people. God was leading and teaching us. We were practicing without a book." In other words, in many ways the Sudanese were living biblically before the missionaries came; they just didn't know it.

Archbishop Daniel weaves his traditional culture and his people's newer, Christian culture together in a remarkably seamless whole. Writers Marc Nikkel and Andrew Wheeler have pointed out that Sudanese ancestral faiths always entailed a most high god, Nyaleech, to whom people turned only in their greatest need and to whom access was limited. They dealt more often with lower, more accessible gods (the jak). Christian leaders called these lower gods demons and named Nyaleech the Father of Jesus Christ. The faith of the Dinka people in particular took off once indigenous church leaders began to take up biblical themes relating to the exorcism of demons.

Andrew Walls, a historian of missions, discusses how non-Westerners have adopted Christianity in their own way, bringing to the rest of the church their culturally specific stories even as they make the stories of the Bible and Western Christianity their own. I saw an example of this process when Bishop Hilary Deng of Malakal explained that he decided to stay in Sudan during the civil war after reading Dietrich Bonhoeffer. "I discovered Bonhoeffer, who remained during the persecution of the Nazis. Whenever we hear of Bonhoeffer now, God uses him to speak to people." The bishop returned from study in Germany to Sudan to be with his people, despite multiple arrests and threats on his and his family's life.

The longer I was in Sudan the more the miraculous nature of the people's tales of resistance to imperialism and the advance of the Christian faith seemed plausible. In 2009, for example, the Ugandan rebels in the Lord's Resistance Army were operating in southern Sudan. Ten thousand refugees suddenly flooded into the town of Mundri, doubling its population. Townspeople and refugees alike gathered at the cathedral, and the church agreed to take the refugees in, with each Mundri family making room for a refugee family under its roof. Tribe did not matter: all were fed and housed for seven days, until United Nations relief began arriving. Why are you doing this? the guests asked. Because God wants us to, was the reply. How will we all survive? The Lord will provide.

When Bishop Daniel arrived in the Diocese of Renk, he saw that the town had a Muslim school on almost every corner and feared that his mission was doomed. "My church is trying to kill me," he said. He was arrested on his first day at his new post. Later, government soldiers commandeered the town's Catholic school to turn it into a barracks. But the Christian townspeople wouldn't stand for the school to be closed. They surrounded the soldiers, then pushed their way into the school and staged a sit-in, singing hymns and daring the soldiers to shoot. One commander was ready to open fire. But some southern Sudanese soldiers in his unit who had been drafted into the national army refused to fire on civilians.

After hearing these and other stories of courage in the name of the faith of the southern Sudanese, I thought of Tertullian's dictum, "The blood of the martyrs is the seed of the church." In some cases Tertullian's teaching is simply wrong. Persecution can choke off the church's life. The designation of martyrdom can be slippery. In southern Sudan some of the killing involved southerner fighting southerner. And some deaths didn't lead to growth, only to death.

Yet Tertullian's claim cannot be ignored where Sudan is concerned. And if the hospitality and faithfulness that I witnessed can continue throughout southern Sudan, then something even bigger than independence will be happening there.